Amidst all the online furore, there is one dimension that has been overlooked in the Monica Baey incident: class.

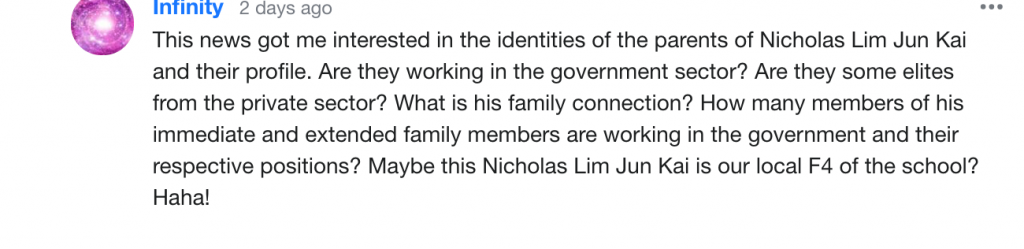

Netizens have speculated that Nicholas was let off with a minor punishment because his parents were ‘powerful people’ who had ‘pulled strings’ with the authorities. Soon after recounting her unfortunate experience with NUS and the police, Monica received a mysterious warning from @jane_tan1996 to beware of ‘angering’ Nicholas’ powerful parents.

Urban legends of prominent citizens using their wealth and power to circumvent Singapore’s meritocratic social order have been a prevalent if underexamined part of Singaporean culture. During my primary school days, it was rumoured that rich parents could buy their sons a place at Anglo-Chinese School—a school long associated with Singapore’s monied classes—with a hefty donation. NSmen still whisper about the mythical ‘White Horse’ platoons, where the sons of ministers and prominent people are supposedly assigned to for preferential treatment.

It is debatable why such myths are so prevalent in Singaporean culture.

Some argue that these myths serve as a coping mechanism against the constant sense of judgement that Singaporeans face in a meritocratic system.

Constantly made aware of one’s flaws in relation to their peers, and being told that one’s mediocre social position is a result of a moral failing on one’s part, these urban legends are arguably subconscious attempts at resisting such stigmatisation. By implying that one’s genuine attempts at hard work have been unfairly undermined by the ‘cheating’ behaviour of more successful citizens, these myths reduce the responsibility they bear for not attaining similar levels of success.

Even then, it is perhaps elitist to dismiss these stories as merely the grumblings of ‘sour grapes’ indulging in the ‘politics of envy’. A more convincing explanation is that these myths are used to reconcile the contradiction between popular conceptions of what Singapore society is and what it ought to be. While Singaporeans do indeed aspire to live in a meritocratic society, we are often disappointed when the society we live in does not always live up to its lofty aspirations.

No country in the world can hope to be a perfect meritocracy. Despite attempts to create theoretical equality of opportunity by instituting processes like competitive examinations, the fact is that family background, social networks, and wealth accumulation inevitably confers individuals with certain advantages when competing with fellow citizens. These consequently result in inequality despite—or perhaps even inadvertently compounded by—the existence of said meritocratic institutions.

It is therefore unsurprising that Singaporeans sense that despite the strong emphasis on meritocracy in our political and socio-cultural discourse, meritocracy does not always translate perfectly into reality. We feel uncomfortable when we notice that places at elite schools are dominated by the children of the wealthy, or that plum positions at work are sometimes assigned to ‘undeserving’ people who have ‘cosied up’ to their bosses. This feeling is exacerbated as the income gap widens—the ossification of ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ creates a discomforting sense that our cherished meritocracy is under threat.

Unable or unwilling to openly state such a controversial opinion, rumours are a covert means of expressing discontent at pockets of unfairness within a system designed to be meritocratic.

Citizens have, however, become more vocal about their concerns regarding the state of meritocracy in Singapore. This year in particular has seen growing debates about education inequality, as Singaporeans increasingly demand a less elitist and more egalitarian education system to better ensure equality of opportunity for all. Young people have been especially active in initiating grassroots efforts to ameliorate structural inequalities in our society.

The government has increasingly taken steps to narrow inequality in Singapore through policies such as the abolition of streaming and the introduction of the workfare income supplement. Yet, the persistent belief that the wealthy and powerful are able to ‘cheat the system’ suggests that more needs to be done to regain public faith in meritocracy. Greater redistributive policies and a more thorough reform of elitist institutions and attitudes should be implemented to further narrow socio-economic inequality, assuring Singaporeans that equality of opportunity still exists.

The belief that every citizen has an equal opportunity to succeed is the cornerstone of our Singaporean identity: it gives Singaporeans a stake in our country’s success and strengthens our sense of belonging to the nation.

While the desire to be a perfectly meritocratic country may always remain an unattainable aspiration, we must take pains as far as possible to uphold this principle and preserve public trust in it. Failure to do so risks creating a sense of apathy and resentment if people come to believes that their efforts at pursuing their dreams are futile in a society where money and power appear to be the only route to future success.