Mary is a foreign domestic worker, whose employers abused her by pouring bleach on her hands and slamming her head against the wall. Eventually, Mary couldn’t take the abuse any longer, and jumped out of her employer’s flat window to escape.

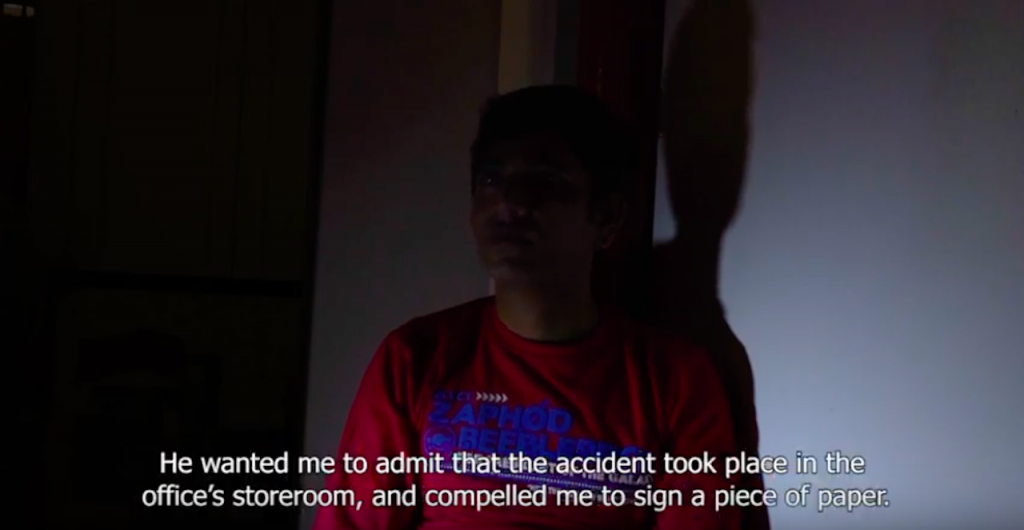

Abdul is a construction worker, who suffered an accident while on site. Three days after the accident, Abdul’s boss threatened him to admit the accident happened in the office storeroom instead, compelling him to sign “a piece of paper”—supposedly an agreement of some sort to ensure his silence.

Iriana is a trafficked sex worker. She only realised what the work she was in Singapore to do was when she witnessed a friend try to communicate with a man on the streets. In her words, she never expected to find herself in a situation where she had to do this “lowest” form of work.

Mary, Abdul, and Iriana are the faces of modern-day slavery in Singapore.

The gripping stories of these three foreign workers are highlighted in EmancipAsia’s 26-minute documentary, Not Here, that premiered over the weekend at The Projector.

The documentary pries apart the carefully constructed veneer of our cosmopolitan city, and looks at the unseen workforce who keep our economy successful. It brings to light the exploitation of foreign workers in Singapore, how our goods and services could be tainted with this enslavement, and what we can do to help on an individual level.

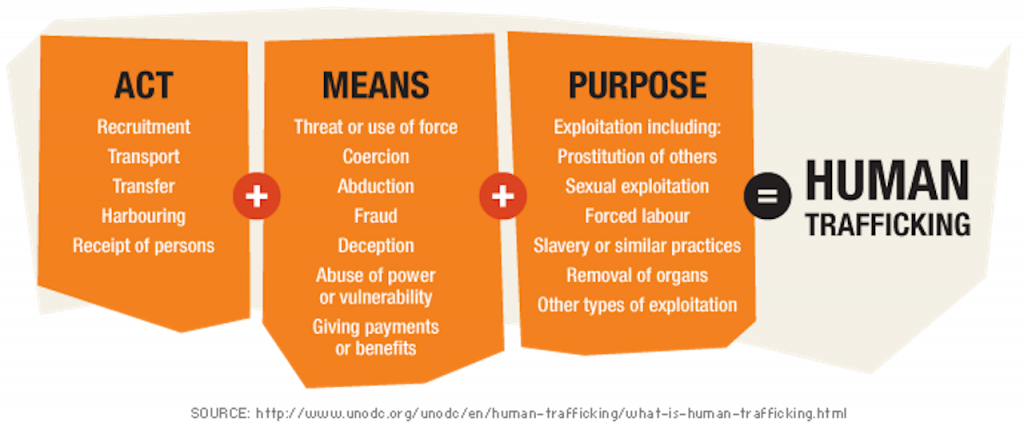

After Mary, Abdul, and Iriana each recount their stories, Not Here dissects how each experience is an example of human trafficking based on a simple equation: act + means + purpose.

Even though this excessive restriction of personal freedom might be considered inhumane to some, normalising abuse begins when we imply that abuse has to look a certain way for us to care. This negates any sense of inherent cruelty in each action.

At times, the documentary and subsequent discussion present dramatic and devastating real-life recounts aimed to shock the audience into action. This includes a recount from a port chaplain, Father Romeo Yu Chang, about trafficked seafarers and fishermen: “Some of them say that because of depression, some cannot tolerate it anymore. They just jump into the sea and take their own life.”

The result is having to confront the uncomfortable realisation that human trafficking isn’t an issue that solely plagues third-world countries.

It is ours too.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Manpower, there were 1,386,000 reported foreign workers in Singapore as of December 2018. This includes 253,800 who held a work permit to be a foreign domestic worker (FDWs) and 280,500 who held a work permit for construction work.

In other words, Singapore’s economy is built on the (literal) backs of foreign labour. In search of a better life for themselves and their families, they raise our children, clean our streets, build our homes, and feed our families.

Yet we continue to treat our migrant workforce as objects or property because many of us don’t care to understand their lived realities, or consider them equal human beings. We reduce them to stereotypes or caricatures to sort them into categories in our minds, especially those we believe should ‘serve’ us, and end up stripping them of any sense of humanity.

The antidote to objectification is empathy. This starts with mindset change, according to Member of Parliament Louis Ng, who was one of the panellists.

Contrary to what cynics believe, a change in mindset isn’t superficial or inconsequential. It’s a realistic and necessary guiding principle for improving the lives of our migrant workforce, and should work concurrently with policy and legislation.

For example, Louis puts up posters of cleaners in his estate that highlight their life stories, including their family and children back in their home country. They too are fathers, sons, brothers, uncles; they too worry about providing for their family; they too deserve respect.

In the grand scheme of things, this might be a small action, but each poster humanises the featured cleaner, returning to them a voice that’s robbed every time someone belittles them.

On an individual level, none of us should be absolved of playing our part even if we don’t personally interact with foreign workers. For starters, Ghislaine Nadaud, a panellist who works as a sustainability expert in a bank, reminds us that we all have bank accounts, and therefore should hold our banks accountable to what they do with our money. We can start by enquiring if and how our banks finance companies and industries with environmental risks, and reading our bank’s environment and social governance reports.

At work, those of us who regularly procure vendors should do our due diligence to ensure we don’t inadvertently enable companies with unethical work practices. Good employment practices right down to the supply chain should be our most important criteria in assessing whether companies deserve the job.

So perhaps the most direct way we can make a difference would be to speak up for foreign workers publicly, interject if we know someone is being abused, and simply treat them as our equal.

While watching the documentary, a memory that constantly came to mind was the time I witnessed a middle-aged man telling off a construction worker, whose construction work had taken up space on a narrow road and hindered traffic flow. The middle-aged man, who was presumably Singaporean (from his accent), hurled vulgarities relentlessly at the construction worker.

All this while, the construction worker was completely quiet, without any hint of retaliation; his entire body was steeped in shame.

I registered a familiar expression on his face: a pitiful reminder that he would always remain an ‘other’ in a country he was building.

In hindsight, this much is clear to me: the construction worker might not have been trafficked nor exploited by his employer, but he was verbally abused by a member of the public. And this middle-aged man’s extreme behaviour was merely a manifestation of a common mindset shared by many others: construction workers fundamentally matter less as human beings.

Not a single onlooker stepped in to stop the middle-aged man’s tirade. They simply looked away, seemingly repelled by both the foreign worker’s shame and their own inability and unwillingness to break free from the bystander effect.

On my part, I tell myself I didn’t speak up either because I was in a rush to get to my destination. But to this day, keeping silent remains one of my regrets.

While abuse of power or vulnerability, among other factors, might create an environment ripe for exploitation, there is no denying that our individual mindsets affect our treatment of foreign workers, the policies and legislation we advocate for, and the way we silence their stories.

Modern-day slavery happens right under our noses. It is everyday life that can be the most damaging—and many of us could be complicit.

I am complicit.