About two years ago, I was about to begin a job with an MNC that I shall not name here. I had signed all their papers, passed the interview, and was ready to start. A month before my term of employment was due to begin, I was called into their offices for what was supposed to be a quick meeting.

When I reached their premises, I was greeted by three women who started out with the usual formalities about the weather, even asking if I’d had any trouble reaching the place. These disposed of, they swiftly began to press the real reason I’d been called in. They had discovered that I had been on hormone replacement therapy (a means of treatment that includes taking hormones such as estrogen or testosterone) for almost a year, and they told me that they would not be able to continue with our agreed period of employment.

They were very careful to tell me that they considered me “very brave”, and that they absolutely were “on my side”, except that they had a family friendly corporate image to protect, and this would unfortunately prevent them from hiring me proper. I pleaded with them, explaining that my transitioning would in no way affect my ability to do my duties and complete whatever work was assigned to me. But it fell on deaf ears.

After the firing was complete, one of the older women took me aside to tell me that she had contacts at a counselling centre that would be able to “heal the brokenness within and without”, and that they would “deal with my childhood trauma”. It was a Christian organisation that she was a member of, and she took the opportunity to proselytise to me before I left in a haze of disappointment and betrayal.

To this day, there is no legal protection for the LGBTQ+ population, who are still seen as undesirable second class citizens, according to such Members of Parliament like Christopher de Souza and Thio Li-ann. Our government does not allow for the gender non-conforming to seek redress in any manner when it comes to discrimination, either from the state or the private sector, and bigotry at the very top levels of government inevitably trickles down to the rest of the civil service, and into society at large.

Three trans individuals, Isabelle (21), Kate (21), and Yuna (20), all of whom have experienced institutionalised transphobia and homophobia, shared such stories with me.

While employed as a tutor at a centre in Serangoon, Kate was forced to deal with colleagues who constantly made life difficult for her when in front of her students.

As Kate shares, “One in front of other students, another privately, in a hallway. My students respect me for my work and address me as ma’am, but about half of the teachers seem to have missed the memo.”

She has been fortunate enough to leave Singapore for Canada, but has observed in local civil servants how societal behaviour inevitably follows suit when when an attitude is institutionalised: “Singaporean transphobia is ingrained into the system. When a country follows a gender binary, transphobia is bound to happen especially when people don’t fit into either box nicely.”

Even though the Standards of Care released by WPATH (the World Professional Association for Transgender Health) indicate that the most successful means of treating gender dysphoria is to allow the person to transition, the Singaporean healthcare system remains several decades behind peer-reviewed and generally accepted science.

Trans people who have not chosen to undergo bottom surgery also exist in a legal grey area, as the Singaporean government does not allow for self-identification of gender, and one must have undergone surgery before gender markers on identification documents can be changed.

This presents a problem because many trans people do not choose to undergo bottom surgery, for reasons ranging from the financial, to concerns about the current state of medical science. When one’s legal documents do not match the gender of the person carrying them, the dysphoria one experiences is severe, which is why so many trans people overseas are battling for the right to express their lived gender on their identification.

Even something as simple as allowing one’s name to be changed can go a long way towards relieving gender dysphoria.

Isabelle’s IC reflects the name of her choice, and she is able to live as herself while she attends university. Thus far, the worse brush she has had with the system was being denied an internship opportunity with a government agency because she outed herself in her documentation. However, it’s in her love life that she’s encountered the most resistance.

Choosing to out herself to potential partners, she often receives answers like, “Oh sorry I not gay I not gay”, or that they “ didn’t come here to date trannies”. This resistance and ignorance is traceable back to the fact that there is little to no education on anything out of heterosexual couplings, with groups like Focus on the Family actively campaigning against expanding sex education in Singapore. This then results in more bigotry and ignorance, which robs trans people of developing a support network.

Support systems, like one’s friends, family, or partner are especially important for trans individuals. Studies into the question of caring for trans individuals show that trans people who face rejection by loved ones have higher rates of illnesses such as depression, and higher rates of suicide attempts.

I couldn’t find any studies that have been conducted into the rates of parental rejection of trans individuals in Singapore, but anecdotal evidence suggests that parental rejection of trans children is particularly high.

My parents are highly religious Christians, and supporters of Trump, so being told that I’m a freak of nature is par for the course at home. Yuna, on the other hand, has not chosen to come out to her family, or to transition, for fear that she will be disowned (or worse). She lives in constant fear of being discovered by her family, which is not the kind of home atmosphere conducive to a healthy mental state.

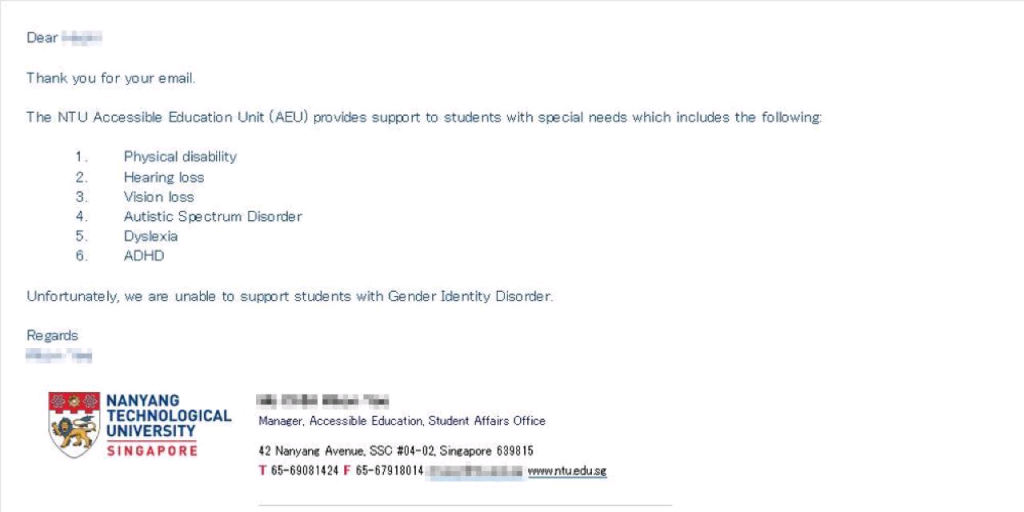

Multiple surveys indicate that Yuna is not alone in this, as trans people in Singapore experience higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation, and this can be tied back to the societal opposition that the community in Singapore faces as a whole. The Nanyang Technological University, for instance has specifically stated that they are “unable” to support students who have gender dysphoria, whatever that means.

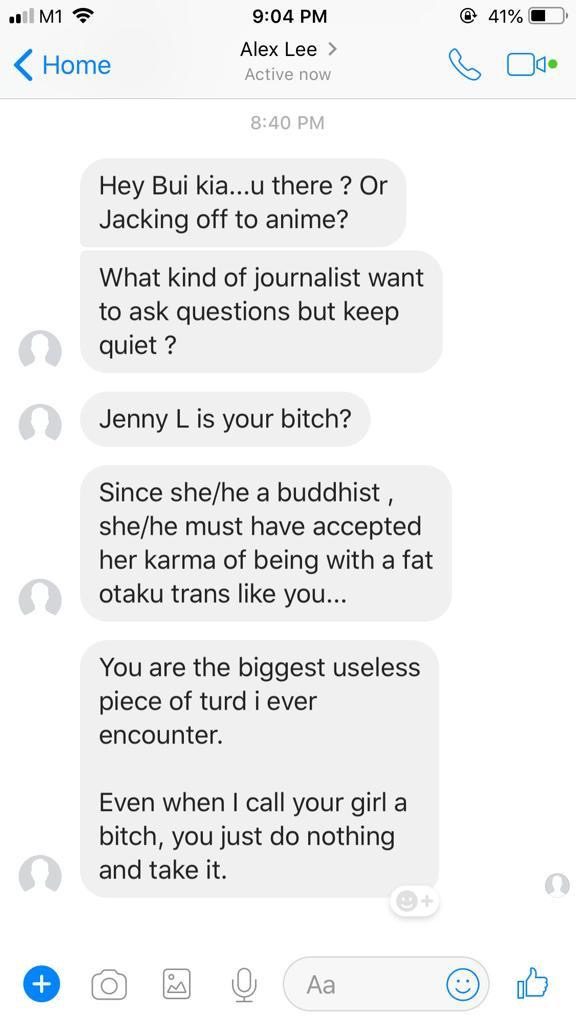

Again, there is more outright government hostility, as evidenced by the action taken by the ROM. And we are all familiar with everyone’s favorite online hate group, We Are Against Pink Dot in Singapore (WAAPD). In recent years, the WAAPD have turned their guns upon trans women, and that venom is hardly limited to members of that group, as I myself had the misfortune to experience when I was interviewing Facebook commenters for a different Rice article.

Yet it would also be inaccurate to dismiss their views as extreme, for they are simply the louder voices of a frighteningly backward majority. From casually transphobic terms like ah gua peng (used to describe how easy our NSmen have it nowadays) to outright violence and discrimination, trans people in Singapore do not have an easy time dealing with casual discrimination. This attitude extends to the government, and especially to the police, who are supposed to be those who protect the vulnerable and disenfranchised.

The Yale Law School Report They Only Do This to Transgender Girls discusses the manner in which Singaporean transgender sex workers are subject to police brutality and abuse of power, with sexual favours such as blowjobs being extorted from the women during arrests and raids, to being forced to strip in front of police officers, to being sexually harassed, with nipples being pinched and prodded during the process of arrest. The manner in which their dignity is stolen reflects how far and how deep transphobia exists in our country.

Transgender people live in a certain limbo in Singapore, a grey area that the government refuses to clarify for fear of offending some unseen portition of the people and their priests.

At the same time, to quote what Kate said to me, “Without transitioning, I’d be operating half as well while suffering the entire time. The second part may be irrelevant to the government, but the first part will allow this isolated community to work just as well as our cisgendered counterparts.”

Worldwide, the trans community faces continued discrimination, and trans women in particular are targets of violence, with at least 37 trans individuals who have been murdered this year. The United States government has begun to revoke the rights that have been extended to trans individuals, with Trump’s ban on trans people serving in the military, and the Trump administration’s plans to define being trans out of existence.

A little closer to home, Mahathir has stated that the LGBTQ+ community is not welcome in Malaysia, and trans people are again particular targets of legal discrimination. In Indonesia, the LGBTQ+ community is being threatened with violence on a daily basis by the state, with trans women being publicly stripped and having their heads shaved to humiliate them by the police.

Trans people live through all of this and much more, and transition so that they can live as their authentic selves.

Let that sink in. Especially for those who are reading and thinking, “If they chose to do that, they deserve what treatment they get”. The trans community endures constant hatred from those who are supposed to protect them. From the police, their families, and from the government that is supposed to defend their rights.

Kate summarises it succinctly, telling me, “The only thing I regret is not doing it sooner. Transitioning gave me the confidence to express myself without being eaten away at the back of my mind. Without exaggerating I’d rather live a day after transitioning than a hundred years before.”

Isabelle echoes this sentiment, putting it far more bluntly: “I’d literally rather die.”

Despite all of this bleakness, one can still hope that Singapore grows and evolves to accept the science behind trans people, and to shed its primitive fears of the unknown. That it grows to become stronger than it was the day before; to become a home that all of us can feel safe and welcome in.