One of the most peaceful spots in Singapore is hidden in plain sight.

On Google maps, it’s listed as “Shuang Long Shan Wu Shu Ancestral Hall”, but a quick search reveals it’s also known as “Shuang Long Shan Cemetery”, “Yin Foh Kuan Hakka Cemetery” or “Holland Close Graveyard”.

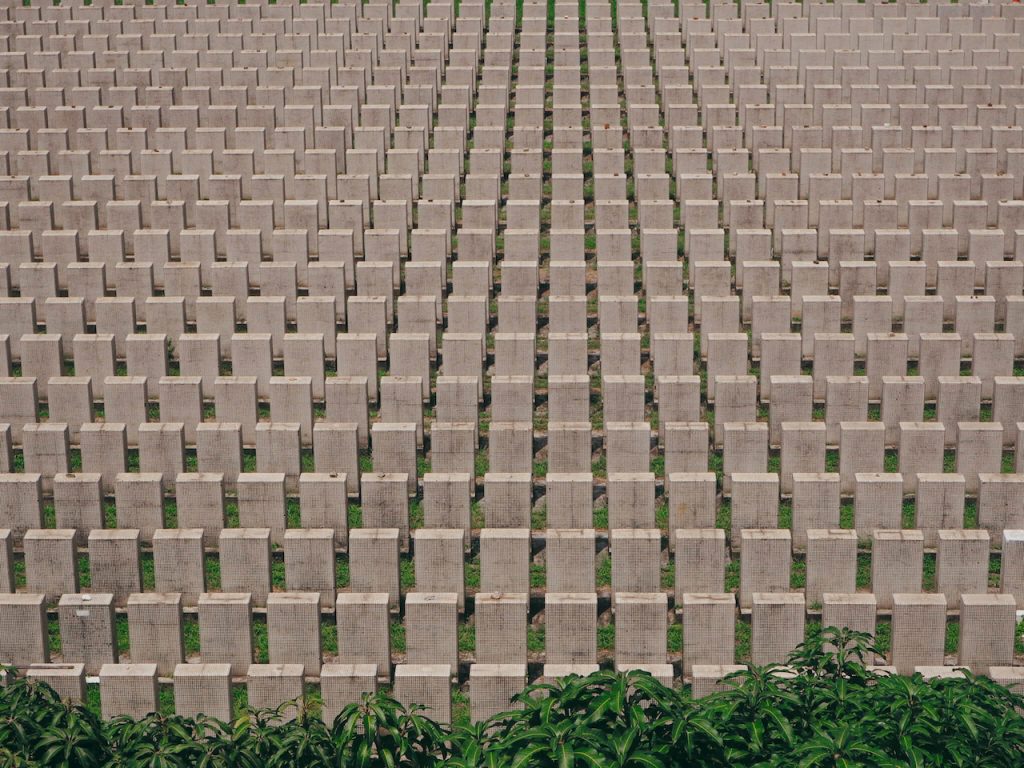

Lying in between Commonwealth Avenue West, a primary road running alongside the East-West MRT line, and a cluster of HDB flats at Holland Close, the cemetery is also flanked by a multi-storey carpark and petrol kiosk. The latter provides a barrier high enough that the cemetery isn’t easily seen when walking along the main road.

To view the cemetery in its entirety, you have to be in a passing MRT train or standing on the higher floors of any of the surrounding flats.

Instead, what’s particularly memorable is the deep sense of calm that overcomes me when I pay the cemetery a visit on an excruciatingly scorching afternoon. Despite its relatively open location, the place is serene and quiet.

And if I stand right in the middle of the tombstones, I can barely hear the traffic less than 100 metres away.

But a quick walk around the cemetery finds me in the company of Teo Ee Koon, the 63-year-old caretaker of the cemetery. He has been manning the cemetery since 1982 with his father, who passed away in 2007.

Everyday, he tidies and sweeps the tombstones. When it’s not Qing Ming Festival or Seventh Month, there are fewer visitors.

All the information above is conveyed using his hand gestures.

But our ‘conversation’ quickly comes to a halt when I realise he doesn’t understand or speak English and Mandarin. Ah Koon, as he is apparently known by the residents who live nearby, only speaks broken Hokkien.

With their help, I soon learn over a few cans of ice cold 7-Up that Ah Koon has never been married and lives with his brother in a small, spartan house on the cemetery grounds. He doesn’t know how to navigate public transport, so he cabs or cycles everywhere he goes.

At this point, Ah Koon offers to let me peek inside his house. Even though it is approximately the size of a one-room flat, it feels spacious because he owns few possessions.

Against one wall, a wooden bench doubles as his bed; there is no mattress or pillow, merely a wooden slab as the latter. Against another wall, his brother’s identical bed stands. (His brother doesn’t work in the cemetery.) The other two walls are lined with a cupboard, a refrigerator, and a stove.

It’s a way of life that I can’t fathom living, yet I envy its simplicity.

Nonetheless, Ah Koon has never felt lonely. To him, love is predestined.

“If you are meant to be married, even if you don’t want it, you won’t be able to escape it.”

Oddly enough, his revelation brings to mind another conversation I had last year with someone around Ah Koon’s age—a taxi driver whom I took to the Marina Bay carnival for a story. Back then, the taxi driver also shared the exact sentiment.

While these were two separate stories, Ah Koon and the taxi driver have each weathered life’s ups and downs. The coincidence of having the two of them tell me that love comes when it does feels like both reminder and reassurance.

They share, “Not everyone can do this job. It takes a rare breed of person. You can tell he is someone who has a good heart and is easily content with life.”

In an interview with Lianhe Wanbao in 2014, which Ah Koon has laminated, he revealed that he has never been to Orchard Road. This was followed by a quote of him wondering who’d take care of ‘them’ if he were to leave.

I assume he’s referring to the dead, which he confirms when he states that he has seen spirits while on the job. Francis suggests that these spirits are probably ‘familiar’ with Ah Koon’s presence, so they make themselves known to him.

Francis shares, “We don’t find it strange to live beside the cemetery. You get used to it. It has become a part of life.”

Similarly, when the Bidadari HDB estate was in the works, Singaporeans were unfazed by its cemetery past. As much as we ‘lose’ heritage when the dead make way for the living, it’s comforting to know that we are not superstitious enough to shun death entirely.

Living next to Shuang Long Shan Cemetery means confronting a sobering reminder of death everyday. Yet against the backdrop of the MRT, a busy road, and tall buildings at nearby Buona Vista, the cemetery is also a stark reminder of life—not the fact that it’s fleeting, but that it’s our duty to live it as honestly as we can.