Smokers just can’t catch a break these days.

A 10 per cent increase in excise duties on tobacco, which kicked in last Monday after Budget 2018, has led to cigarette prices going up once again; this time, by $1 at the minimum.

While the tax is designed to reduce smoking rates by making cigarettes less affordable, it hasn’t really had an impact. Tobacco duties were last increased in 2014—also by 10 per cent— and yet the proportion of smokers between the age of 18 and 69 has still consistently hovered around 13%.

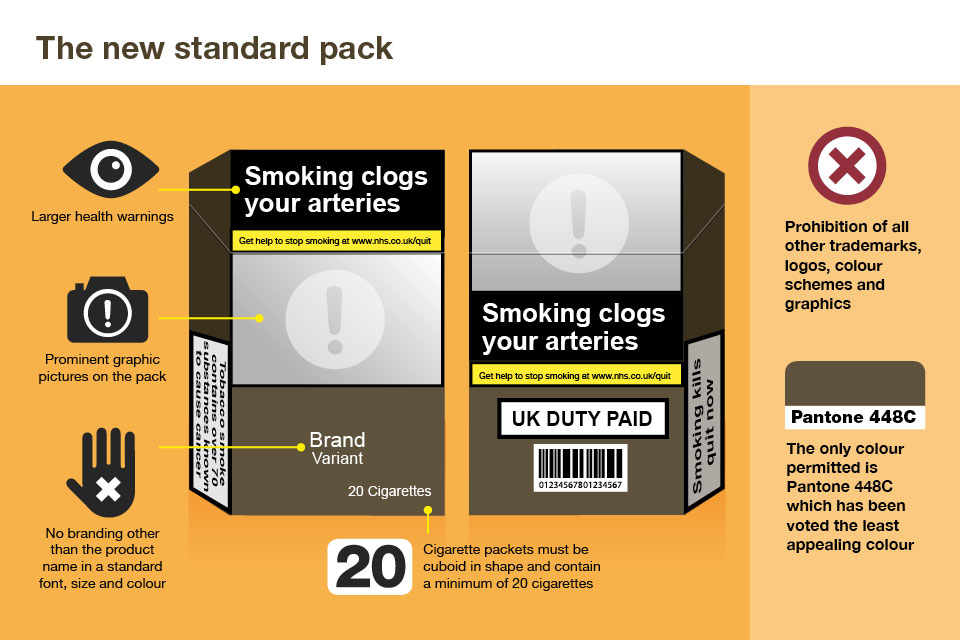

If this increased taxation doesn’t yield results (other than more revenue for the government), standardised tobacco packaging will be the next anti-smoking weapon in its heightened war on tobacco.

Currently in the middle of a six-week public consultation phase, this will remove all forms of branding on tobacco products.

Following the display which ban came into effect just last year, along with the progressive increases to the legal smoking age to 21, it seems the authorities are going to great lengths to get Singaporeans to quit smoking.

But these measures are not enough.

Chances of this law coming into effect are very likely. But would it actually have an effect on reducing smoking rates?

Data from Australia, the first country to introduce plain packaging, suggests not. Since the law was implemented in December 2012, the country has not seen any significant decline in the daily smoking rate.

In fact, considering that Australia’s population has increased, the figures indicate that the number of smokers in Australia has actually increased after the introduction of tobacco plain packaging, says Sinclair Davidson, an economics professor at RMIT University.

Yet Australia’s experience is still extensively cited in the Singapore proposal to justify the need for standardised tobacco packaging here. That the Australian government has won lawsuits filed by tobacco companies and tobacco-producing countries has emboldened other governments to follow suit. France and UK have since implemented a similar law, while Canada, like Singapore, is mulling over the proposal.

“Nobody likes the tobacco industry. The tobacco plain packaging law is the cheapest policy that makes life difficult for the industry and looks good to voters. But it does nothing to actually stop smoking.”

He also urges Singapore to re-examine the data from Australia, which he claims is heavily flawed, as well as wait for more concrete data from France and the UK before coming to a decision regarding plain packaging.

Last December, French health minister Agnes Buzyn admitted that the country’s plain tobacco packaging law had been a failure as tobacco sales had actually increased since its implementation, casting further doubt on the plain packaging law’s effectiveness.

“Arguments against the tobacco industry would work nicely in Australia, France, UK and Canada,” says Prof Davidson. “The Singaporean government has always prided themselves on being sensible and responsible people who look hard at the evidence and make pragmatic decisions. But plain packaging runs counter to that because it is a populist move.”

The result is merely replacing one problem with another, instead of actually achieving the objective of reducing smoking rates.

In Australia, nearly 15% of tobacco consumed in the country is smuggled in (typically first purchased legally in Asia), and even legal tobacco stores (known as tobacconists) are known to sell contraband products under the counter.

With Singapore already facing its own problem of tobacco smuggling from across the Causeway and Indonesia, there is cause for concern as to how a standardised tobacco packaging, coupled with the newly implemented excise duty, could lead to a black market.

Such a situation could become further complicated and harder to police, given that illegal and contraband items have already made their way onto online marketplaces and chat groups in Singapore.

There is also the fear that there will be no limits to what the government can do in its war on tobacco once the plain packaging law is approved—draconian legislation that will lead to trickle-down effects on other economic and sociocultural aspects.

For instance, with the health authorities taking a harder stance on sugar, would soft drinks and other sugary foods also be obliged to utilise plain packaging to deter sweet cravings and reduce the risk of diabetes?

And should the government decide to further reduce the exposure of the young to tobacco products, could that lead to censorship of all portrayal of tobacco in the media?

Such an idea is no mere hogwash. The Motion Picture Association of America was hit by a lawsuit in 2016 seeking an injunction where no films featuring tobacco imagery can be given “G”, “PG” or “PG-13” ratings.

A similar collaboration between the Health Ministry and the Information Media Development Authority would spell a nightmare for consumer rights.

“It’s dull and hard work, but you got to keep re-emphasising and changing the message,” says Prof Davidson.

Even with easy access to information on the Internet, the government still has a crucial role in educating the public instead of simply using legislation to discourage smokers.

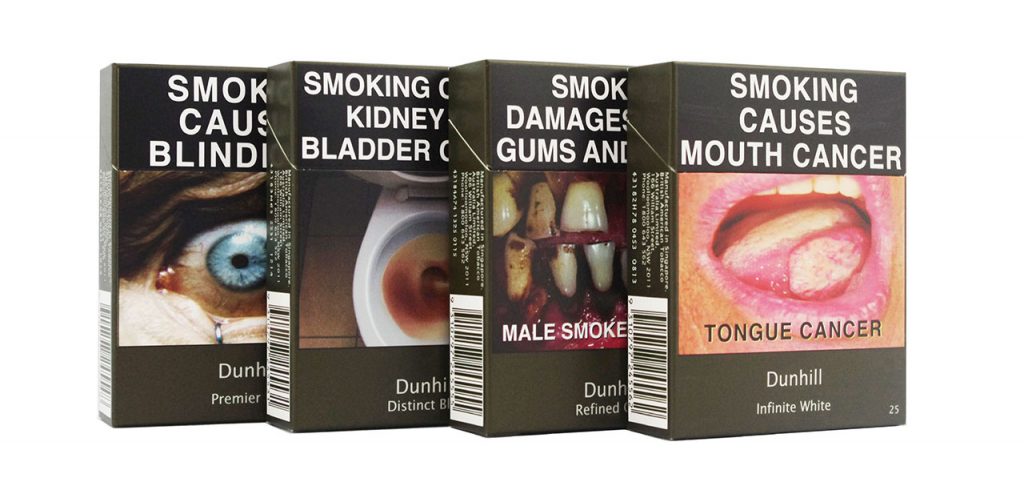

He adds, “I don’t think providing public information makes the government a nanny state. A combination of tactics, some purely informative and others ‘shock and awe’, are likely to be effective. Looking at past anti-smoking campaigns in the ’90s, the Singaporean authorities are very innovative in this space and more work should be done in this area.”

Have something to say about this story. Write to us at community@ricemedia.co