It was pouring so heavily yesterday at 6 PM that there were fears the highly anticipated triple-combo lunar eclipse might not even materialise.

The last time the astronomical event happened, inelegantly termed a “super blue blood moon” like the title of a rap song, was 152 years ago in 1866. We will not live to see another occurrence in our lifetimes.

Yet perhaps opening the heavens was god’s way of telling us that after dumping so many Obikes into drains and canals, we don’t deserve nice things.

Fortunately, an hour later, the rain subsides, the clouds start moving north, and all eyes turn to the skies where a brightly shining moon would gradually fade to dark.

More than half of the moon has already lost its shine as the Earth’s shadow looms larger on it, and the lit portion forms a crescent that resembles a tiny fingernail protruding out of a black glove.

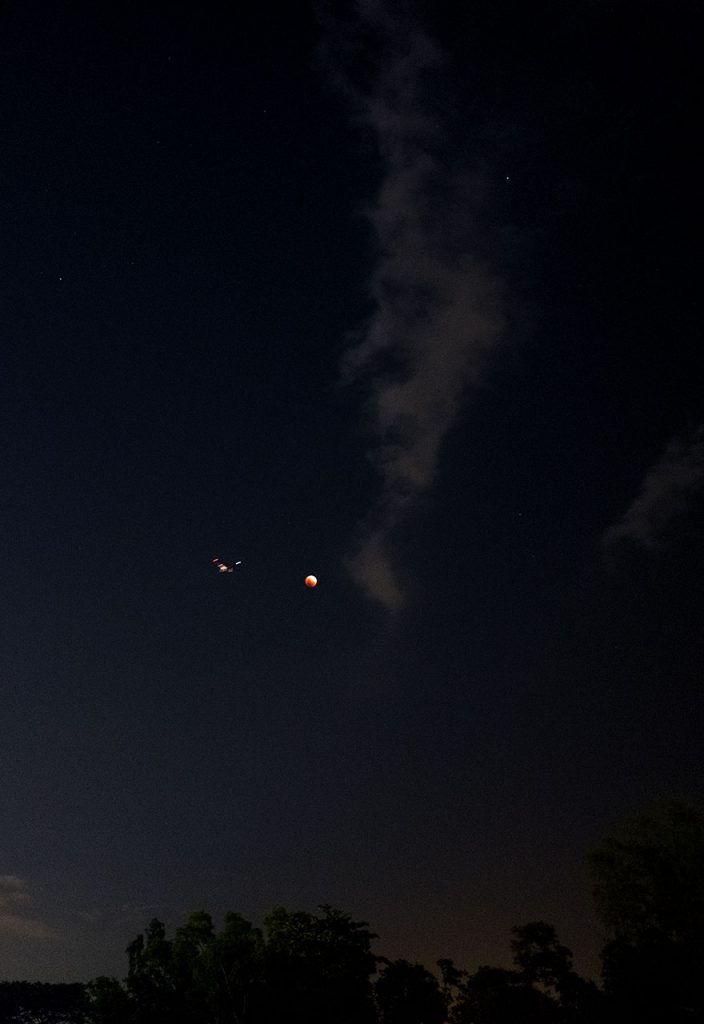

A friend, concerned that I’m late to the party, texts to ask if I can still see anything. I send a photo of a white speck in a grainy black sky, the best that my phone’s camera can manage.

But the some 50 stargazers and photographers who have already lined themselves along the perimeter of the field have come much more prepared than I am. They have set up about 20 telescopes – some even with equally expensive cameras attached – pointing towards the celestial body in the sky. Someone has even brought a portable music player to blast Coldplay tracks.

I hazard an estimate of $100,000 worth of equipment on this muddy field.

Many of these professional hobbyists have been camping inside the station since evening, praying for the rain to stop. Whatever they did, it worked. Their spirits may have been dampened earlier, but now the field is buzzing with activity as the community gushes about the clear visibility that their patience has been rewarded with.

In fact, Remus, who is also the co-founder of local astronomy forum SingAstro, is so passionate about his hobby that he is intending to stay on for the full duration of the eclipse even though he has a flight to catch at 1 AM. “I don’t want to miss any major astronomical event. Anyway, I’ve already packed my luggage,” he tells me.

Remus may be a renowned photographer, but he’s also a great teacher. While fiddling with the exposure settings on his camera, he is also patiently explaining the science behind the “super blue blood moon” to curious members of the public who, without any special equipment of their own, can only resort to using their phones to photograph the close-up shots of the moon’s reddish surface displayed on his camera’s screen.

Someone observes that the camera cannot take a completely accurate exposure of the eclipse in one shot. Like an enthusiastic science teacher addressing his class, Remus says loudly, “That’s right! In fact, the naked eye can see the eclipse better than our camera sensors, does anyone know why?”

And just like any other classroom, no one wants to answer the question for fear of saying something stupid and being judged for it. A brave soul shouts, “Because we are organic!” Everyone laughs.

Later, I also discover that the moon actually looks inverted through the telescope’s viewfinder. Special converters can correct the orientation, but they would also compromise the image quality.

Murmurs and groans start to emanate from the field. A stray, trespassing cloud has appeared out of nowhere, gliding right into the path of the eclipse, partially obscuring everyone’s view.

“Just a passing cloud,” someone confirms and there is a collective sigh of relief.

At 8.49 PM, the subdued roar of an aircraft’s engines can be heard. What ensues is a five-second frenzy like a scene from a war movie.

“Aeroplane! It’s going past the moon! Faster shoot it!”

“Did you get it?”

“Did anyone get it!”

“No, the plane was too far [from the moon]!”

More groans.

The moon is now a dark disc floating in the sky, though the blood red appearance is much more accentuated through the telescopes.

I expect some sort of celebration, maybe a Kallang wave even, but apart from a cry of “Totality!” from one eager photographer, the reaction to the total eclipse is largely underwhelming. Everyone seems more focused on nailing the perfect super blue blood moon shot on their cameras.

I also get the sense that most are simply exhausted from having to wait for more than an hour to witness the moon going dark completely, unlike a solar eclipse which happens very quickly and has an instant captivating effect.

“See, they know how to pin this on me,” laughs Mr Tan Hoe Teck, the club’s teacher-in-charge.

Mr Tan tells me that unlike most of the stargazers here, he is not keen on taking “pretty pictures”.

“I’m more interested in the data so that I can plot a graph to show how the light spectrum changes during the eclipse.”

He reveals that he is also setting an exam question based on the eclipse.

Mr Tan’s interest in astronomy was inspired by a university professor who taught him a module while he was pursuing a degree in physics.

“To me, astronomy is best appreciated when you are studying the fundamentals of science, so that you can actually understand what’s happening in space, for example the movement of light and particles. There’s so much to uncover than what we just see with our eyes.”

He adds that through the use of relatively affordable kits, he hopes his students would develop a deeper love and understanding for science by forcing them to be creative with less resources.

“SST does not receive as much funding as other secondary schools. But you don’t need to use the most expensive equipment to teach students, what’s important is the way you teach them.”

Like many of those who have skipped dinner for this once-in-a-lifetime natural occurrence, I hurriedly take my leave to grab a bite.