In Singapore’s own Black Mirror universe, some of us worry that the government is policing our every action. The reality is that the most extreme form of surveillance comes from each other.

Every few months, a new ‘name and shame’ social media post goes viral to remind us that this is the most effective way to get justice when we feel wronged.

From bad customer service to cheating partners, one moral transgression and someone’s public reputation risks irreversible damage. Usually, these misdeeds aren’t illegal, but cross wider society’s moral and ethical threshold.

Still, we want the perpetrator to pay, no matter the cost.

And the ‘best’ part about the court of public opinion is that the person being ‘shamed’ is deprived of a voice. They are irrevocably guilty until proven innocent (if ever).

But let’s be real, the main goal in naming and shaming, or sharing name and shame posts, is because they make us feel better about ourselves. They are essentially self-indulgent ways of seeking justice.

And there’s nothing wrong with being honest about this.

Naming and shaming feels good because it simplifies a complicated world and separates it into black and white, right and wrong.

Not only do naming and shaming posts communicate a deeper desire for revenge, they also show that we aren’t someone to be trifled with. There’s a perverse satisfaction in seeing people, who have gotten away with corrupt behaviour for far too long, get their due punishment.

It’s also easy to get behind naming and shaming when the wrongdoing is so horrible that we assume we’d never act the same way. Ironically, this culture makes us overly cautious of our behaviour, since we never know what others might take offence at, or when we might be next.

In the long run, this means we may never actually internalise what’s right or wrong. We figure it’s more important to stop distasteful behaviour than to understand where it comes from.

In December last year, Singaporean Ashry Owyong Min (pictured above) gained notoriety when he was discovered to have cheated on his girlfriend, influencer Chloe Teo, with three other girls and one guy. The five-timer’s behaviour was almost psychopathic, as screenshots on Chloe’s Dayre recount displayed blatant lies and a complete lack of remorse.

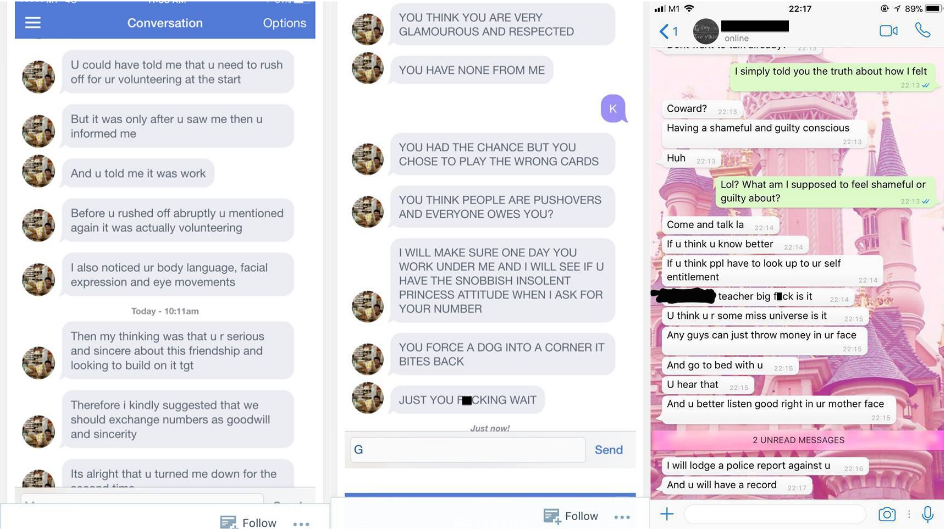

In the same month, influencer Melody Yap shared screenshots of her friend getting harassed by a “psychotic creep” called Wenhui Tan after she rejected him. Screenshots showed Wenhui making serious threats and insults against women. According to Melody’s now-deleted post, police reports had also been made against him.

Both the aforementioned cases allowed other women to come forward with their own experiences dealing with Ashry and Wenhui.

Witnessing all this transpire online, I admired these women for publicly broadcasting Ashry and Wenhui’s actions, and felt further glee when both men were ripped apart in the comments section. I relished that they would never get another job or find another girlfriend the ‘normal’ way, as long as someone is able to google their name.

In some way, the underdog ‘wins’ when social media validates their suffering. Sharing what we’ve been through and watching others get angry for us feels cathartic because we are assured that our suffering matters.

Besides, if we already have sizeable social media followings, why not use it to our advantage to ‘raise awareness’ about the problem?

But most of us are bystanders like me, who live vicariously through name and shame posts. Our own lives remain unaffected, but we enjoy seeing justice being served nonetheless. We may not even have encountered similarly traumatic experiences, but we would gladly share these posts.

Like reality TV, they are thoroughly entertaining and essentially remind us our own lives are not so bad after all.

That said, both the feeling of ‘winning’ and the joy of being part of an online lynch mob can wear thin very quickly. This satisfaction may even be superseded by a growing discomfort.

With the culture of naming and shaming now a firm part of social media, I’ve realised that it has become our natural instinct to take to social media to mete out punishment we deem fit for those who have ‘wronged’ us.

Accordingly, this fuels an impulse to feel as though our suffering needs to be validated, never mind that reality is usually more complicated and rarely black and white.

So even though we may not be the most upright, we want to think we’re above Ashry Owyong Min and Wenhui Tan.

After all, moral superiority is a drug with an enduring high.