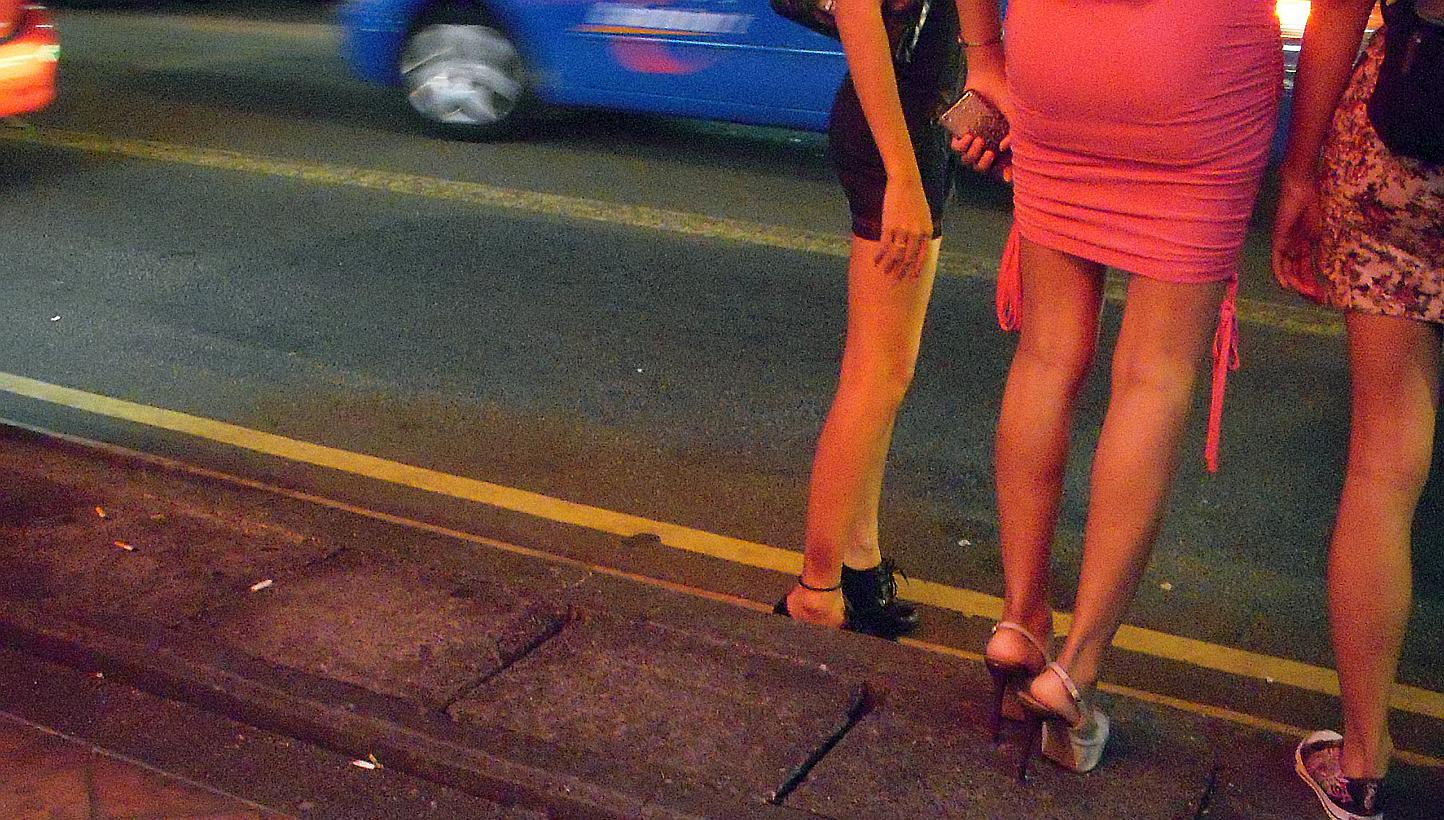

Geylang is synonymous with two Singaporean icons: great food and a bustling red-light district.

While the government has adopted a tolerant approach towards the latter, it also regularly dispatches anti-vice squads to raid brothels and nightclubs in the area.

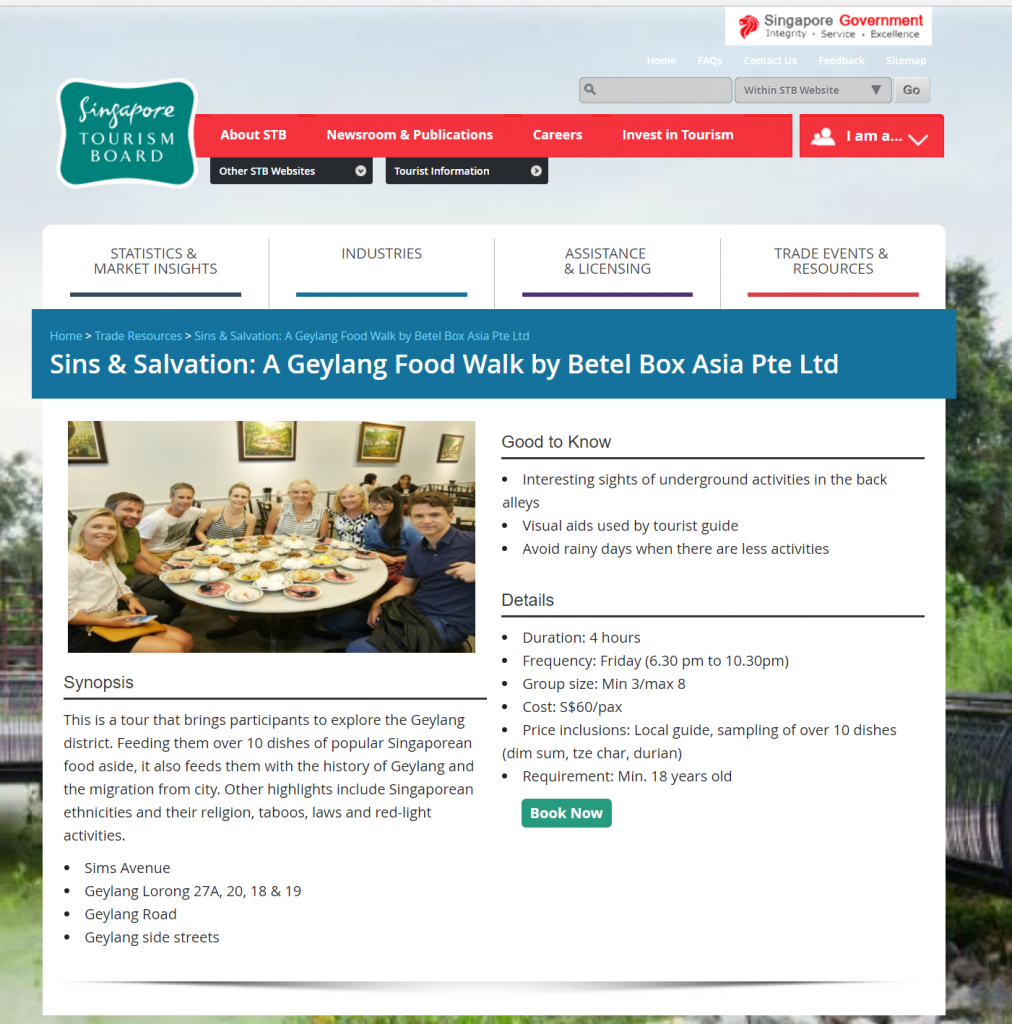

At the same time, Geylang, once (and still) the poster boy for Singaporean vice, is now touted as a tourist destination that showcases the grittier side of a largely “pristine” city.

Take this tourism advertisement on the Singapore Tourism Board’s website for example:

How are we supposed to see Geylang: a museum exhibit of a darker yet vibrant and necessary side of Singapore’s society? A place to bring our foreigner friends to show that Singapore isn’t as boring as they think it is?

Is it not hypocritical that we promote it as a tourist attraction, but at the same time demonise prostitution when it reaches the heartlands?

Last week’s news of yet another brothel in a HDB estate may come as revolting to many who feel aggrieved that the sanctity of a HDB flat has been encroached upon by vice.

Questions have been raised about whether customers are just as guilty as those who offer promiscuous services, and the need for tighter regulations by the Housing Board to ensure flats are not misused; that those who need a roof over their heads are not deprived.

But if this really is the problem, why not crack down on flats being repurposed as workers’ dormitories too? Why the double-standard?

All this simply overlooks the bigger picture and the elephant in the room: why has the government still not presented a clearer stance on prostitution in the country?

For instance, it is a common misconception that sex workers are formally licensed. Rather, they are issued permits by the police to ply their trade. At the same time, they are not legally required to produce this permit to customers when asked, and there are no legal ramifications if they refuse to do so.

They are also not allowed to solicit under the Miscellaneous Offences (Public Order and Nuisance) Act, while the Women’s Charter criminalises pimping.

In addition, the Women’s Charter stipulates that brothels are illegal. This may come as a surprise, considering the world-famous status of Geylang’s notoriety as a red-light district. Still, the brothels continue to operate in a few traditional red-light areas thanks to special licenses issued by the police’s Specialised Crimes Branch, also known as the anti-vice department.

The exact nature of these licenses are considered a secret, with zero information provided on the Singapore Police Force’s website.

And so we see the paradox of the government’s stand on prostitution.

On one hand, the official viewpoint is that sex work is a vice, hence laws are implemented to curb it. On the other, the authorities know that it would be impossible to clamp down entirely on such activities, and thus have elected to turn a blind eye until it receives complaints from the public.

Hence, the government’s pragmatic approach, with regular checks and enforcement against prostitutes and pimps who solicit in public to “contain the situation”.

Centralising the brothels in a few key areas like Geylang and Little India also ensures that the police can monitor and take action more easily, as dispersing these brothels to the whole of Singapore would lead to a case of them “operating everywhere” and thus a game of cat-and-mouse.

But the recent trend of illegal brothels moving into the heartlands suggests that this precautionary measure is no longer working. In actuality, the sourcing and booking of prostitutes now take place online, making it harder for the police to suppress such vice activities.

According to a Straits Times report, at least 82 women have been arrested for suspected involvement in vice activities in residential areas since January this year.

The dispersal of prostitutes into residential areas such as Yishun, Sembawang and Ang Mo Kio is frequently attributed to the increased anti-vice crackdowns in Geylang. This is part of a massive cleanup operation that has been ongoing for a few years now, following complaints by residents and MPs about the rowdiness in the area.

In fact, the problem of residential brothels is not a new one. Way back in 2000, reports of vice-related activities in the heartlands had already surfaced in the mainstream media, and this was just a year after Wong Kan Seng had explained the government’s stance on prostitution.

Baey Yam Keng, then MP for Tanjong Pagar GRC, voiced his concerns about the consequences of a Geylang cleanup in an interview with the Straits Times, “They are spilling out because of the raids. People accept what they do in Geylang, but may not be used to it elsewhere.”

The “not in my backyard attitude” among Singaporeans when it comes to prostitution and sex work has been vehement. It is also downright hypocritical.

Like our attitudes towards workers’ dormitories, we have no qualms about prostitution in “faraway” or cloistered places like Geylang, but react with disgust when sexual activities proliferate within proximity of where we live.

Yet while residents claim that the presence of sex workers and strangers in their neighbourhoods “endanger their safety and that of their children”, such transactions are largely discreet. They have to be in order to remain undetected by the police, and by far and large, the people involved do not bother those who live in the area.

You never hear residents complain about solicitation or harassment from sex workers and their customers at their void deck.

So in reality, nothing bad ever happens. Or at least not more so than usual. And it is mainly the idea of living within close proximity of “sleaze” and the “possibility of STDs lingering in the corridors” that turn many Singaporeans off.

This stems from a societal perspective that still discriminates against those who work in the sex trade, even if they have been allowed to do so by the police.

To some extent, religion also has a hand in shaping our frame of mind. Conservative values propagated by Christianity and Islam have led many to frown upon premarital sex and thus condemn the act of paying for sex.

Instead, we should be rethinking our attitudes towards prostitution, which has already existed in ancient times. Why should we deem the actions of human nature between two consenting adults as morally unethical, or evil even?

Ultimately, if the government knows that prostitution will never cease to exist, and fully criminalising it would almost certainly drive the industry underground, then they need to change their approach.

Instead of the current inconsistent stance that is inherently hypocritical, perhaps we should just fully regulate it.

In the same parliamentary debate where Wong Kan Seng reiterated the government’s stand, J B Jeyaretnam asked the minister, “If it is felt that you cannot control it, then is the Ministry considering legalising prostitution and containing it to just one or two areas in Singapore and keeping a strict watch on the premises which indulge in this?”

Mr Wong then replied that there was no need to do so as the situation could still be dealt in a “pragmatic” way.

This question was raised once again in a 2013 issue of the Law Gazette, the official publication of the Law Society of Singapore. In the article “Sex, Money, Lies and Punishment”, penned by lawyers A Sangeetha and Eoin Ó Muimhneacháin, it was proposed that the inherent paradox in the law on prostitution could only be resolved by amendments in two forms: full criminalisation or full regulation.

Under the latter, a statutory board would be established to regulate and license the sex industry, which would also prevent the exploitation of underaged sex workers.

I ask Mr Muimhneacháin whether he still believes in this approach, four years on.

He cites the increased cost of comprehensive regulation, the increased public health risks associated with venereal diseases, and the likelihood of more people being forced into sex work out of economic necessity or poor decision-making as the main drawbacks to fully regulating prostitution.

Still, it does not mean that current laws are adequate.

“I do think I would personally lean more in favour of full regulation than full criminalisation … I believe that the current expression in law of the government’s policy on the sex industry betrays an incoherent or not fully thought out policy,” he says.

If the government is worried that having an official red-light district would tarnish its image as an unblemished country, then the STB advertisement above directly contradicts this view.

Ms Vanessa Ho, director of local sex workers’ rights group Project X, cites the example of Germany, which has designated areas where the police protect sex workers there. This is the opposite of the situation in Singapore, where the police are typically on the hunt to arrest sex workers.

“A lot of the conflict surrounding the issue of prostitution arises when sex work happens in residential areas. People are under the impression, or even brainwashed to think that sex work is dangerous and sleazy. Hence you get all these vigilantes stalking the sex lives of their neighbours. So to ease conflict, no matter how ill-informed, a designated area might help,” she says.

But it is unclear whether Geylang will even get to hold on to its red-light district notoriety in the near future, as rumours of gentrification in the area have begun to swirl.

If that indeed transpires, then the complications resulting from a disrupted sex trade is unfathomable. A dense migration of sex workers to all parts of Singapore, as long as rent is cheap, would surely happen.

Only then might the government realise that conducting more anti-vice operations in the heartlands does not address the root of the problem, and that dealing with the situation in a “pragmatic” way is often more easier said than done.