However, the enemy is not an Indonesian commando waging Konfrontasi or the yet-unborn Al-Qaeda franchise Jemaah Islamiyah.

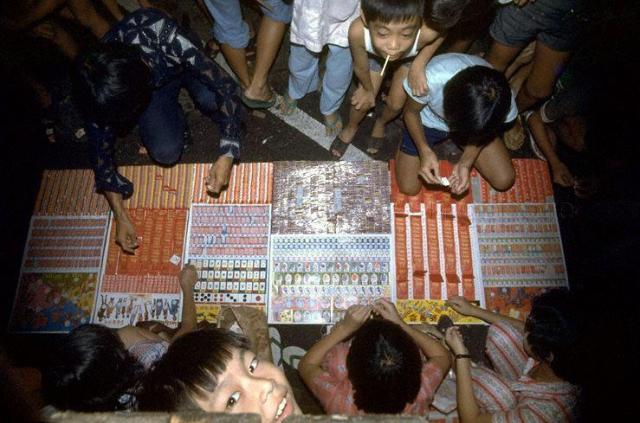

Instead, it was a nefarious homegrown terrorist—the Tikam Tikam man. Armed with his Tikam board and an arsenal of delicious snacks, he would set up shop outside a school to corrupt innocent school children, turning them into ‘scoundrels’ and ‘gamblers’ with his seductive game of chance.

For 5 cents, you could get an envelope with a number inside. This number corresponded with a prize on the Tikam Board, which could be a toy, a piece of stationery, a snack, or if you’re lucky, something even bigger!

And hence, many kids would waste their lunch money trying to win the top prize at Tikam Tikam. A fool’s wager, because as a government report notes, the top prize had no corresponding number and was thus un-winnable.

In short, Tikam-Tikam was not only illegal but completely rigged.

In 1970, a massive police raid seized 12 Tikam boards from an operator, along with 180 packets of popcorn, 47 packets of prawn crackers, 24 toys, and 220 sweets.

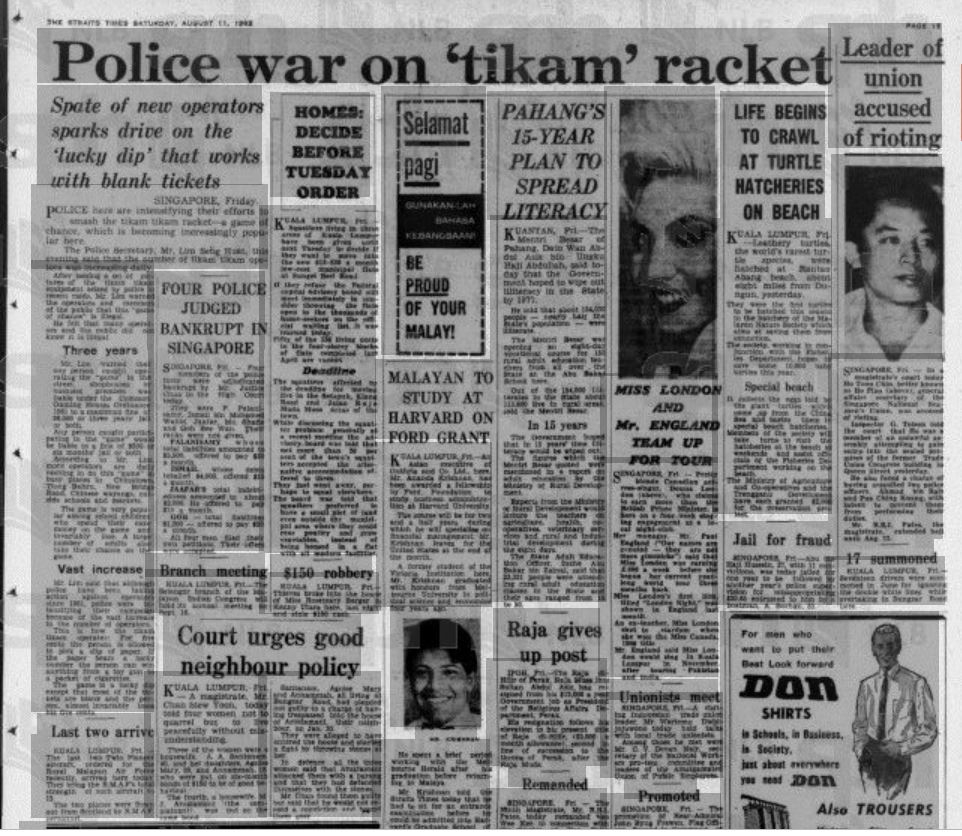

Yet the Tikam menace did not abate. In 1975, there was a crime wave and more than 28 people would be arrested for preying on children with Tikam Tikam.

Many citizens were naturally outraged. They found it ridiculous that something as minor as Tikam Tikam should trigger such a disproportionate response from the authorities. It was, after all, a ‘petty’ game of chance. The government, however, did not agree. Stressing the dangers of Tikam Tikam, the police inspector argued that “operating a Tikam Tikam might seem like a minor offence but a lot of schoolchildren have fallen victims …”

If gambling is so evil that 5 cents can destroy a child’s future forever, how did we reconcile it with our decision to build a casino?

This is the question that is raised and answered in Professor Lee Kah-Wee’s book ‘Las Vegas in Singapore: Violence, Progress and the Crisis of Nationalist Modernity’. Recently published by NUS press, it is a fascinating study of Gambling’s long history in Singapore, as well as the government’s (colonial/PAP) paradoxical, love-hate relationship with the ‘vice’ of gambling.

As most Singaporeans can recall, the decision to build the integrated resorts was a controversial one. There was widespread opposition on the ground, from various religious groups, as well as in parliament itself.

The main worry was the social problems which might arise after opening a casino. Hardly surprisingly given our long history of prosecution, not to mention demonization.

In order to execute a moral U-turn, the government had to come up with the various solutions like the $100 entry levy on locals and the name ‘integrated resorts’ — which ‘disappeared’ the casino from public view whilst legalising it at the same time.

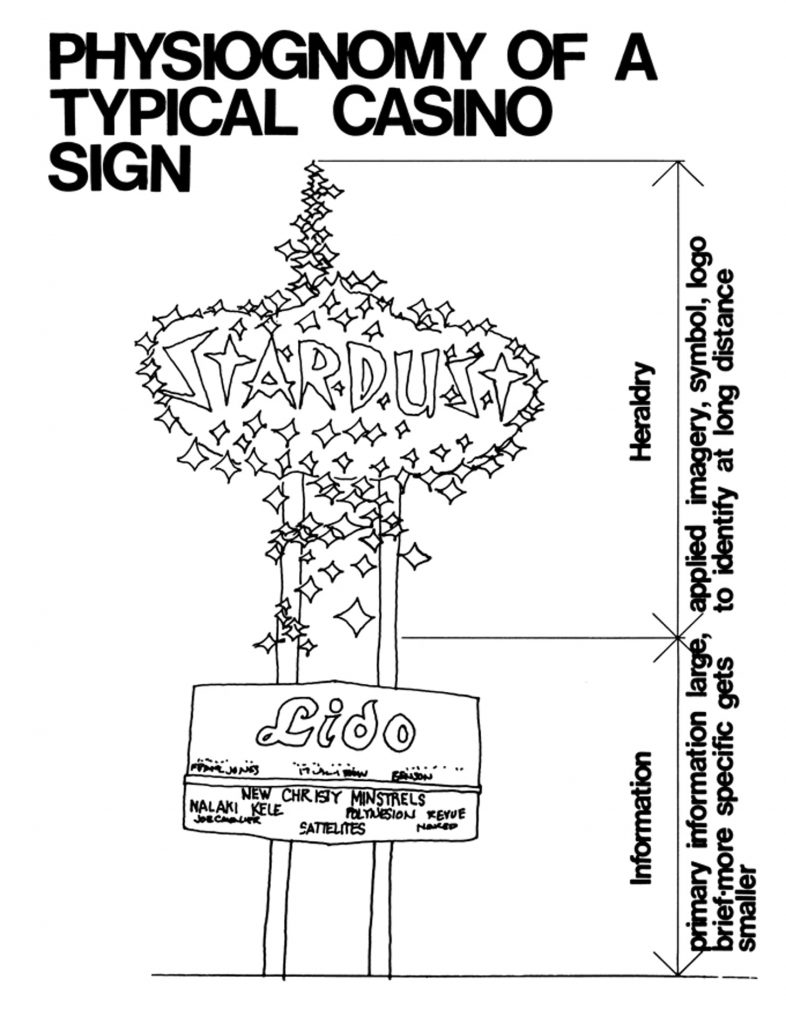

This strategy of ‘vanishing’ the casino is also manifested in the architecture of Marina Bay Sands itself, which does not conform to the design template of most casino-resorts in Las Vegas and Macau.

Sands CEO Sheldon Adelson’s original plan for the Marina Bay Sands did not contain the now-infamous sky park and infinity pool, which he saw as a pointless distraction from the profit-maximising purpose of a casino-resort. He also wanted the casino to have a strong ‘Venetian’ theme in line with his company’s brand, and a monorail connecting the casino to the International Ferry Terminal.

None of his dreams materialised because his advisors persuaded him to go along with the government’s vision. As a result, Marina Bay Sands is the only Sands casino where the location name (Marina Bay) precedes the brand name (Sands).

The ‘Venetian’ theme was likewise scaled down in favor of a more MICE-convention-centre aesthetic which fit in better with the government’s vision. However, what distinguished MBS from other Sands casinos – or casino-resort in general – is the unique ‘effacement’ of the actual casino from its architecture.

This was the original plan for MBS as well, if the original architect Paul Steelman had had his way. Steelman’s MBS version 1.0 was a tropical-themed IR (because S’pore lol) which placed the casino front-and-center. Although it was tucked away behind the ‘civilising’ facade of a museum, the actual casino was nevertheless the first thing you saw upon entering, whether you entered from the waterfront or Port Cochere.

This was of course too much for ‘principle of zero visibility’ and Steelman was replaced by Moshe Safdie, an Israeli-Canadian architect who eventually gave us MBS as we know it.

Even the choice of architect was rather symbolic, as it turns out. Steelman was an experienced casino architect who literally wrote the book on casino design. He was famous for designing Sands Macau, City Of Dreams Macau, amongst many others.

His practice, Steelman Partners, is devoted almost exclusively to the design of casino resorts.

In normal circumstances, this would be a plus because you would be hard-pressed find a more experienced or successful casino architect than Mr Steelman. In Singapore, however, his credentials worked against him. Or as Prof. Lee writes, his expertise in creating ‘architectural reasons to gamble’ was too much for the ‘official veil of propriety’.

The Casino was moved out of sight, the monorail was scrapped, and the resort building itself was placed firmly in the context of a larger ‘waterfront promenade’. The end result was an IR which looked more like the Sydney Opera House than its true cousins in Vegas and Macau.

Fortunately, it was exactly what the government wanted: an architectural condom which would sanitise—and contain—the sin of gambling.

In 1965, LKY wanted to build an offshore casino on Pulau Sejahat, but he would later reject Stanley Ho’s proposal for a casino on mainland Singapore with the words: ‘no, not over my dead body’.

In 1968, at the height of the War on Tikam, Toto was launched with the help of Bulgarian advisors. To avoid the charge of hypocrisy, all proceeds from Toto were used to fund the National Stadium—an important totemic landmark for nation-building.

In 1999, the Turf club was moved from the centrally-located residential area of Bukit Timah to the desolate nothingness that is Kranji.

Professor Lee sees these events not as isolated incidents, but parts of a larger policy where vice is condoned and erased at the same time. Using strategies of space and architecture, gambling, that so-called ‘congenital weakness’ of the Chinese, can be both controlled and exploited without any disruptions to the ideological consistency which underpins our social conservatism. Just as we keep sex work and the plight of migrant workers out of sight and out of mind, the same is true for gambling, which is pervasive, necessary and completely invisible.

So what does this history mean for ordinary Singaporeans?

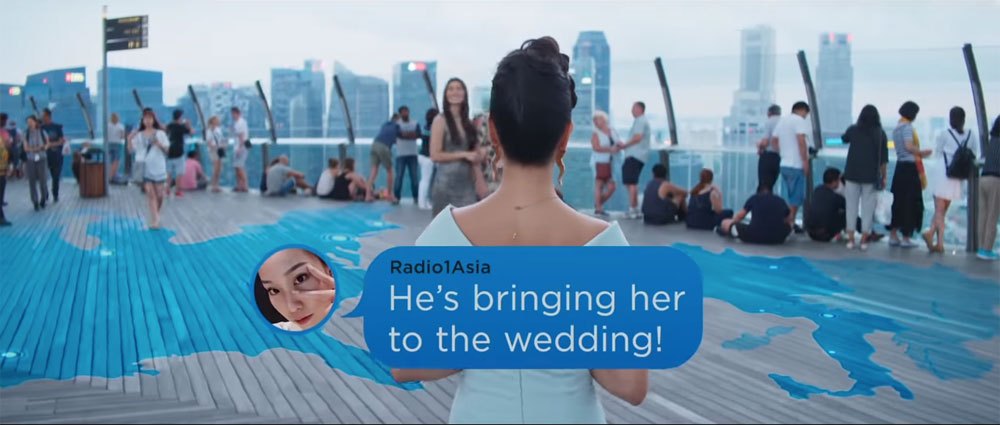

These days, Marina Bay Sands is the national icon.

Whether you are making a sequel to Crazy Rich Asians or shooting a CNN segment about the Trump-Kim summit, your producer will force you to use MBS as a background, possibly at gunpoint. This is because—thanks to time and media exposure—it has become a sort of visual shorthand for the cosmopolitan, globalised ‘Brand Singapore’ that our government wants to sell to investors and which hardcore Brexiters invariably adore.

However, what they fail to understand is that the MBS version of Singapore comes at great cost. It is the product not of liberalisation but of highly illiberal policies. It is, as Professor Lee demonstrates, an illusion of progress without cost; of profit without penalties; an illusion made possible by the linguistic euphemism of an ‘integrated resort’ and the architectural euphemism of Mr. Safdie’s beautiful lie.

So the next time you see MBS on your newsfeed, spare a thought for the Tikam Tikam operator, the kopitiam gamblers, the Chinatown Duck gamblers, and other forms of street-level gambling that has vanished forever. Those three pillars are not just a symbol of our nation’s heroic progress. They are also a symbol of state power, and its ability to reshape the narratives around gambling.

Some would call this hypocrisy. For others, it’s often called ‘progress’.