Most of the residents I spoke to for this story requested anonymity as this is a sensitive time for the ongoing en-bloc.

Many of the HUDC estates and older condominiums already sold in this year’s seemingly unceasing spate of en-blocs will likely see them torn down and rebuilt for luxury, high-rise living. But in the case of Pearlbank Apartments, it might not be so straightforward.

As one resident tells me, “The only reason we signed was that Colliers had a dialogue session with us who weren’t for en-bloc, where they promised they would promote both conservation and redevelopment to potential buyers. Otherwise they would never, or at least I don’t think they would, have reached 80%.”

“They even said that they would put together a promotional video with drone footage to sell this idea,” he said.

If this does indeed happen, it will be the first time in Singapore’s history that a multi-strata owned residential project would have achieved conservation with re-development via an en-bloc. So in spite of the en-bloc, Pearlbank will get to retain much of its original architecture.

Completed in 1976, Pearlbank Apartments is undoubtedly one of the most iconic buildings in Singapore.

But it is also not one that has aged well—an oxymoron that defines many of its residents’ sentiments towards the current collective sale attempt.

Over the course of 3 afternoons, residents shared with me their reasons to either sell or hold. The one thing I hear about the most is the problem of water leaking from units on upper floors to lower ones. This is largely due to how the building’s piping is made from cast iron, which many manufacturers had already begun transitioning away from in the 70s.

At a recent AGM, a proposal was raised to collect a “special levy” to contribute to Pearlbank’s dwindling sinking fund. This levy ranged from $300 to $1000 a month for 2 years, depending on the individual share value of units. This would allow the replacement of a stack pipe which was causing one of the building’s major leaking issues.

However, this proposal was voted against.

On top of this, the lifts break down on a regular basis, and there have even been rat infestations.

As writer and researcher Justin Zhuang explains, Pearlbank was built during Singapore’s property boom in the early 70s.

Its original developer had to reckon with material and labour shortages, and a “cast in-situ” method of construction meant that “the vertical elements went up so fast that the horizontal elements, notably the in-situ split floors and staircases, experienced a hard time trying to catch up”.

Currently, with access to limited funds, Pearlbank’s management has had to balance between replacing and repairing parts of the building.

“There’s nothing like it,” one tells me.

Another echoes, “If you want space like this in other parts of Singapore, you can dream on.”

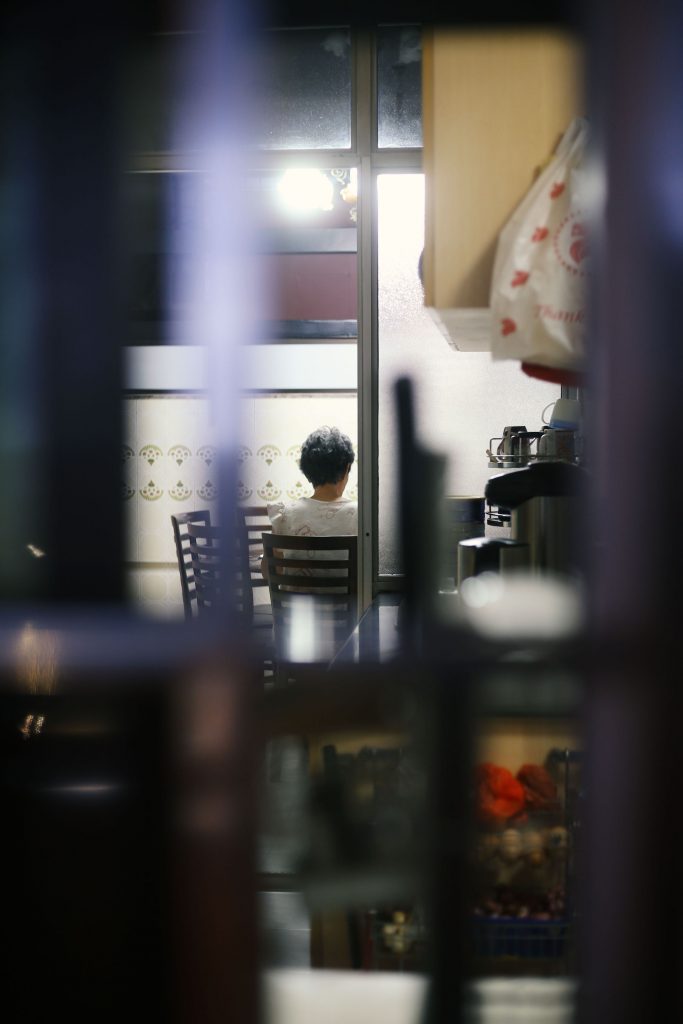

Then there are the older residents who have lived in Pearlbank for more than 20 to 30 years. They worry about whether they’ll have enough space for their belongings when they move. Many are sentimental about the building as well, and are hesitant to give up the proximity to Chinatown.

It doesn’t help that some of these residents share their homes with younger relatives.

While they want to stay put to live out their golden years in peace, their children and grandchildren worry about whether a short lease and the deteriorating condition of the building will hamper their chances of eventually selling off their units when their parents pass on.

Yet despite all these disagreements and conflicting perspectives, one thing is clear: apart from those who bought units here as an investment, none of those I spoke to actually want to move. En-bloc is simply the next best option after an attempt to conserve the building in 2015, following 3 previous en-bloc attempts, was unsuccessful upon failing to meet the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s requirement that all unit owners agree.

Back then, Pearlbank’s original architect Tan Cheng Siong proposed that the five-storey carpark be demolished to make way for a new block of 150 apartments. It would even include an infinite pool.

The sale of these apartments would then pay for both the refurbishment of the existing Pearlbank tower and the topping up of its lease (which it is nearly halfway through). Then residents of Pearlbank would not have needed to fork out a single cent.

Many signed immediately, excited at the prospect of having the apartment block refurbished, and having the remainder of their 99-years leases topped up.

Unfortunately, only 91% of owners assented. When I ask several residents about this, they lament, “I tell you ah, honestly, URA was stupid to have insisted on 100%.”

“Under BCA’s Building Maintenance and Strata Management Act (BMSMA), any proposal that impacts the ownership rights and share values of existing SPs can only proceed if there is consent from all of the SPs.”

While this sounds fair, it’s worth noting that in comparison, only 80% of consensus is required for an en-bloc to proceed.

It then occurred to me that as condominiums get taller, shinier, (and tinier), private developments that share the architectural uniqueness of Pearlbank will soon become a rarity. Iconic and well-located developments like The Interlace and Sky Habitat, for instance, have 99-year leases.

So what happens 30, 40 or 50 years from now? Will the residents of these (and similar) developments find themselves in the same situation that Pearlbank is now in?

If yes, what will their options be?

Does it have to be en-bloc or, as some residents have said, “accept it and move on with life”?

With the options facing Pearlbank, there is an opportunity for a compromise of sorts.

If both conservation and redevelopment can happen, current residents who are sentimental about the place can choose to buy back units and return to a place that still looks like home. Others will get to enjoy potential financial gain, and those who wish to see the endurance of Pearlbank’s unique architecture will be appeased.

It will be a favourable outcome for all stakeholders.

One resident shared his hope that Colliers would emphasise to potential buyers that Pearlbank is an iconic landmark that can be easily transformed into service apartments. It could also house an Outram Park Medical Residence to service the SGH Campus which is being developed nearby.

“En-bloc with conservation will be a unique development of the urban Singapore landscape,” he added.

At the same time, there is no guarantee that Colliers will be able to find a developer who is keen to pursue such an arrangement. As the Business Times notes, Pearlbank currently comprises 280 apartments with 8 commercial units. But the site has the potential to be redeveloped into 730 new residential units with an average size of 800 ft².

Previous attempts at an en-bloc have also been unsuccessful, and it remains to be seen if the “en-bloc fever” of this year, along with the fact that the Singaporean government no longer has any land parcels left to sell to developers, will change anything.

While Minister Wong was referring specifically to public housing, this clarification has undoubtedly led to a nationwide reckoning with the ticking time bomb that is the 99-year lease. It’s part of why so many en-blocs have already happened.

In a way, 99-year leases and en-blocs exist to keep housing “affordable” while also offering residents a possible bailout of sorts when the time comes. Property portal 99.co also explains that en-blocs allow land scarce Singapore to be constantly redeveloped.

Even then, it’s worth asking when it will all finally be enough.

Will this seemingly endless cycle of en-bloc, redevelopment and land use intensification be something Singaporeans should come to expect as a way of life? Should those of us who don’t live on freehold land start learning to accept that ‘home’ can only ever be a temporary concept?

Thus far, the country hasn’t yet gotten to a point where the oldest of its 99-year leases have started to expire. Hence, there’s no better time to start thinking about how one should approach the future of housing in Singapore: with cynicism, hard practicality, or flexibility?

As Tan Cheng Siong himself puts it, “You can’t talk about preservation in architecture. It’s conservation. And conservation means also you can adapt, reuse … but the whole meaning, the whole spirit behind still remains.”

What Pearlbank now has is a new way forward. It’s also an opportunity to remember that if places like Pearlbank are good enough to appear in Singapore’s Passion Made Possible video, accompanied by the lines “There is no place like this / This is the place”, it should be good enough to be worth keeping.