First, they took away shisha tobacco and hookahs, citing a need to reduce the public’s tobacco consumption. Now, the authorities are not sparing the “healthier” alternative to tobacco cigarettes either.

A total ban on electronic cigarettes, which was passed in November last year, will come into effect in the next few months.

Vaping has in recent years been regarded as a successful way to quit smoking. On a Reddit page dedicated to the testimonies of ex-smokers who kicked the habit with the help of e-cigarettes, Redditor dontpanic4242 shares, “I started vaping in 2014 […] I tried smoking one a few months back while I wasn’t drinking and I couldn’t even finish half of it. Everything about it was horrible. I’m so glad I’m not smoking anymore.”

Unfortunately, Singaporeans hoping to vape away their smoking habits will still have to rely on nicotine patches and gum, as well as a whole lot of self-discipline.

What makes the government’s decision more baffling is its outright rejection of evidence that support the use of e-cigarettes.

Parliamentary Secretary for Health Amrin Amin said in November that the health ministry was not convinced that imitative tobacco products could help smokers quit because such evidence was “neither robust nor conclusive”, and such studies could have been financed by tobacco companies.

That is no different to how climate change deniers have continually rejected the global phenomenon on the basis of their own data and scepticism of existing research.

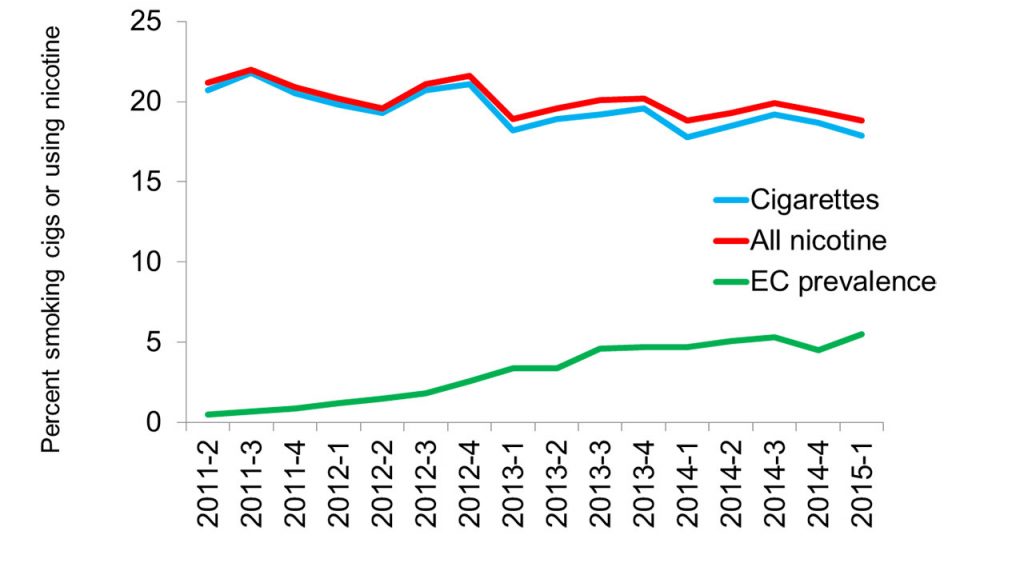

Mr Amrin added that the number of e-cigarette smokers in the UK, where vaping is publicly supported and advertised by the national health agency, had increased four times to 2.8 million between 2012 and 2016.

Concurrently, he ignored the fact that the increasing use of e-cigarettes in the UK had also led to record-high success rates of smokers quitting the habit, according to a report by University College London released two months before he addressed parliament.

Instead, the government has opted for the more restrictive route of the US, where the view that e-cigarettes are a gateway to nicotine addiction continues to be rooted.

Even with the plethora of case studies available, the government has cherry-picked data that suggests e-cigarettes are detrimental to health, regardless of whether they may be just as inconclusive as data that shows otherwise.

More recently, a Straits Times report on Monday also further reinforced the official stand on e-cigarettes, publishing only quotes from smokers that were in favour of the ban.

Perhaps this also explains the rationale behind the ban in Singapore. The country has historically adopted a “no-nonsense” approach towards drugs and substance abuse with harsh jail sentences and even the death penalty, though it is arguable that they are thoroughly effective in fighting drugs.

The authorities would not risk opening the floodgates if they cannot ensure that e-cigarettes would not become a new form of addiction picked up by non-smokers. It’s a chewing gum ban travesty all over again.

This “government knows best” prescriptive approach has also riled up many Singaporeans, as Facebook and Reddit comments illustrate. Instead of actually listening to real sentiment on the ground, the authorities have gone ahead to make the decision on behalf of all Singaporeans.

The government, it seems, thinks that Singaporean adults are children who cannot make their own decisions, and has fuelled the suspicion that banning e-cigarettes “in the interest of public health and safety” is an exercise in smoke and mirrors.

As one Redditor puts it: “[The authorities] are not willing to spend the time, effort and money into figuring out how to regulate and tax e-cigarettes. At the same time, they do not want to lose tax revenue from traditional cigarettes to e-cigarettes. So the easiest solution? Ban e-cigarettes.”

If taxation is indeed a consideration, then perhaps the ban is the only way for the authorities to get out of the catch-22 situation, which is to figure out how to implement a tobacco levy on a product that they want to incentivise smokers to switch to.

Furthermore, an impending tax hike—expected to be announced during the Budget address on Feb 19—could comprise an increase to the “sin” tax on alcohol and tobacco, further complicating the problem of e-cigarette taxation.

It’s a chewing gum ban travesty all over again.

The official position is also untenable when the health ministry has not provided data to show the effectiveness of other forms of replacement therapies like nicotine patches and gum either.

From 2019, the minimum legal age to purchase cigarettes will be raised from 19 one year at a time until it is set at 21 in 2021. The same can be done for e-cigarettes as well.

Because e-cigarettes have been marketed as a new electronic gadget that looks cool and is fun to use — youths are easily hyped over the exhaling of massive clouds of vapour that is currently in vogue — the authorities’ concern of e-cigarettes’ appeal to the young is not unfounded.

It is also widely accepted that e-cigarettes alone cannot drastically reduce tobacco consumption. Rather, they should be used in conjunction with other forms of quit-smoking avenues in order to be effective.

So why not offer them as a medical prescription by doctors to help smokers quit smoking? That would ensure that the device and its liquid content would not be abused.

Indeed, classifying e-cigarettes as a form of medication would require more time and resources to research, but a total ban only puts this beyond the realms of possibility.

To be fair to the authorities, public health messaging is a conundrum because it cannot be nuanced.

As Sarah Zhang writes on the US’s hard stance on e-cigarettes in Wired, “You end up hitting people over the head with just one message or the other.”

However, let’s not forget that when the ban kicks into gear, it could open up a black market for import and distribution of e-cigarettes. That would be a whole other problem which could have been avoided in the first place.