Why is live music banned for Thaipusam but not for St Patrick’s Day?

This was the question on everyone’s mind when the police issued a ‘public entertainment license’ for last weekend’s St Patrick’s Day celebrations permitting the playing of musical instruments—a right that was denied for the Hindu celebration of Thaipusam just one month before.

Naturally, outrage and accusations of hypocrisy ensued.

The government’s excuse for this apparent “double standard” was that we are comparing apples with oranges. St Patrick’s day is a cultural procession, while Thaipusam is a religious one.

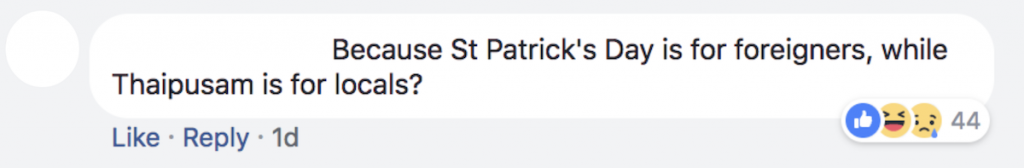

Of course, this explanation did little to temper online expressions of exasperation.

At the same time, the wrongful (or rightful) classification of St Patrick’s Day as a cultural celebration was never what this was really about. Rather, it was how the allowances made regarding St Patrick’s Day have been read as yet another instance of preferential treatment of ang mohs (white people) over locals.

Prior to this incident, Singaporeans have hardly—if ever—rallied against the supposed unfair treatment of Thaipusam despite the fact that musical restrictions on the festival have been around since 1973.

Even now, as Singaporeans express their indignance on behalf of Thaipusam, many stop short of calling for the reinstatement of the festival’s right to its musical instruments. Anger and effort is instead spent on denying the Irish a place in Singapore and denouncing the existence of leprechauns.

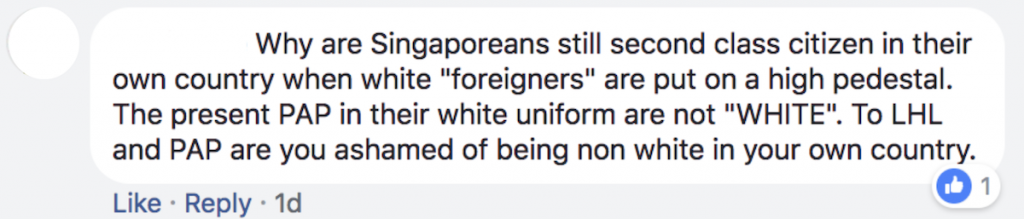

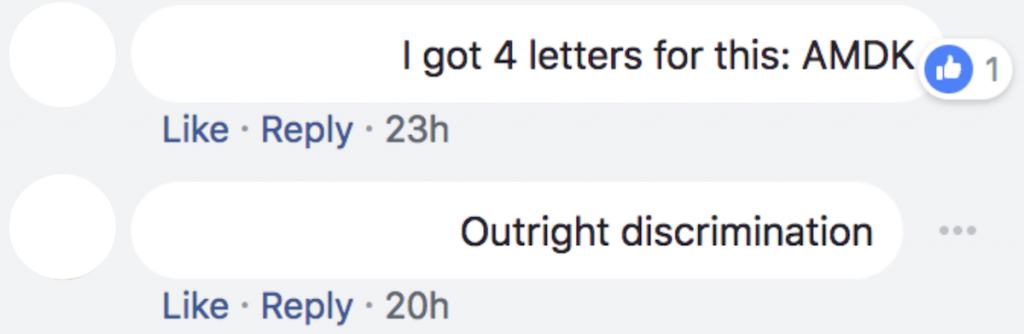

It’s no secret that anti-foreigner sentiment amongst Singaporeans has existed since the beginning of time, giving birth to terms like “AMDK” (ang moh dua kee or white people big shot) and ‘foreign talent’.

The Thaipusam vs. St Patrick’s Day debate is merely the latest incident supporting the belief that expats have it better than the rest of us average, non-Caucasian Singaporeans.

If we really want to make a difference and be rid of this inequality, what we need to do is resist making this issue about foreigners and focus instead on where the real problem lies: with the outdated and antiquated laws governing Thaipusam and religious processions in general.

Perhaps the 45-year-old ban on the use of musical instruments during Thaipusam was relevant during a time when fights between competing groups were common and would threaten to disrupt the procession.

But given that it’s been decades since a notable riot broke out during the Hindu festival, it’s high time the law be relooked.

I also believe that society has since matured enough to know that if racial riots don’t result from regular (usually Taoist or Buddhist) funeral processions and festival marches like the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, the same can be expected for Thaipusam.

One argument that Singaporeans often put forth is that most processions happen during the day and not overnight unlike Thaipusam. As such, the ban on musical instruments is necessary so as to not disturb Singaporeans.

But as one commenter on Facebook aptly put it, “When fellow Indians can tolerate a month of smoke and burnt ashes that float into our household and loud music from Getai performances, ain’t the Indians tolerating this for Singaporeans.”

This, I would argue, is the issue. Not the fact that we, as another eloquent commenter put it, “Are always opening our legs for ang mohs.”