On 26 June 2018, former residents of Rochor Centre finally had their iconic homes demolished seven years after they first received notice that they were part of the Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS).

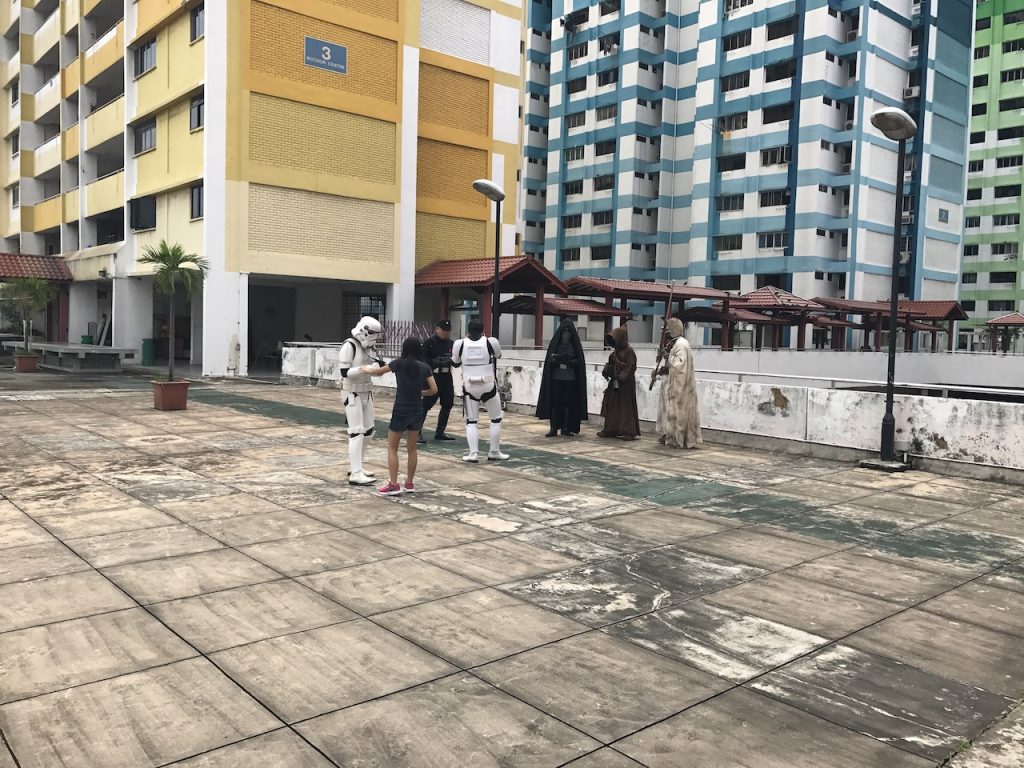

In the years after the announcement, Rochor Centre’s final days followed a sickeningly familiar narrative. Everytime a heritage landmark is torn down to make way for the nation’s progress, Singapore collectively goes through the five stages of grief.

First, there is denial, which is unexpectedly short-lived.

Next comes anger, an emotion easier to admit than hurt. Online commentaries and personal essays furiously lament our government’s economic decisions.

Then, bargaining. Someone somewhere decides to create a petition on Change.org and manages to get thousands of signatures, hoping this will encourage the government to reverse their decision.

Following its glorious failure, depression sets in. During this stage, the initial anger underpinning every photo essay and commentary gives way to a blanket of nostalgia. Several events pop up in remembrance of the landmark.

And finally, acceptance. In this case, the residents of Rochor Centre began their goodbyes even before they knew their home would be put up for en bloc, aware that it was only a matter of time before the government realised their home lay on prime land, and demanded it back.

“We always suspected that something was going to happen, when some shops could not get their lease renewed. But the announcement still came as a shock, primarily because we’d endured the construction of the Downtown Line right outside our flats,” he shares.

“We’d put up with it for a few years, in hopes that we’d enjoy convenience and connectivity eventually. In the end, it felt like it was for nothing.”

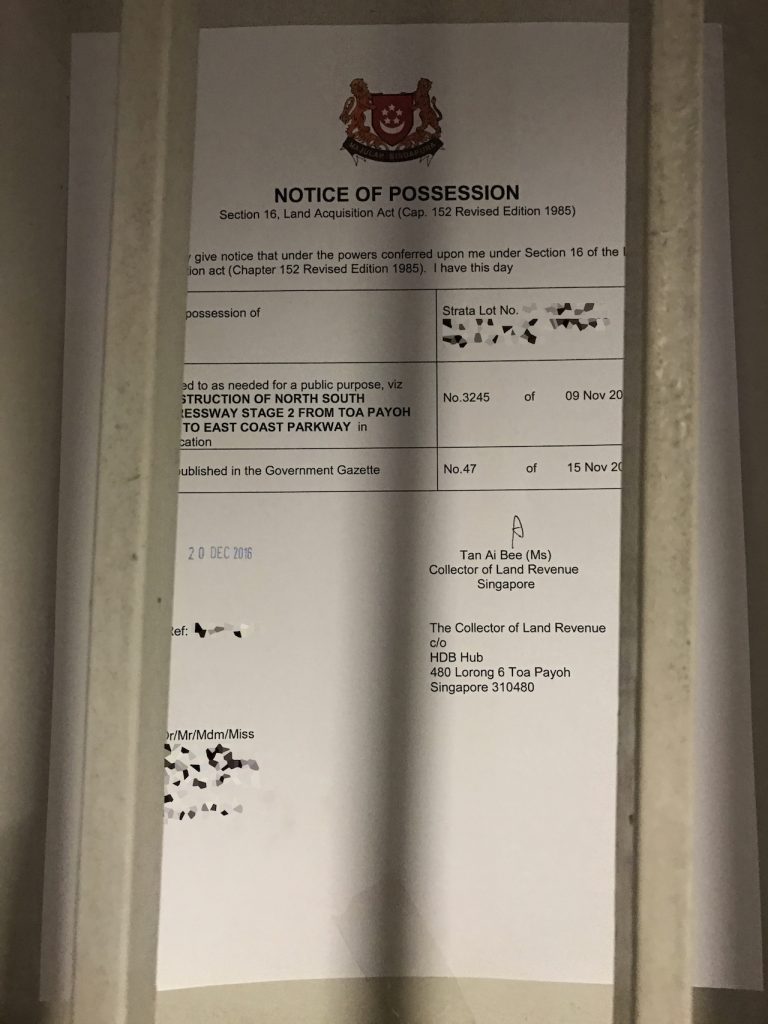

“I opened the front door and saw the en bloc notice pasted on it. It informed my family that we had to vacate by a certain date.”

Samuel remembers feeling “quite upset”, but that initial disappointment was soon exacerbated when he visited the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) headquarters for a school project shortly after the announcement.

There, he saw a miniature model of Singapore.

“I noticed Rochor Centre was replaced with an odd looking building that was designated as a mixed-use development. I was upset because we were told we were moving to make way for a highway, yet I go to URA and see that they’re planning to build a shopping centre or office building there,” he explains.

In fact, Samuel recalls that his mother used to walk to Suntec City from home.

Yet he echoes the resignation shared by other residents, “What else could we do?”

70-year-old Mdm Yeoh Hong Keow shares that it made her sad to relocate at first, but she has since settled in. She enjoys that there’s a senior activity centre at the void deck, where she spends time with her fellow residents whom she knew from Rochor Centre.

Perhaps because of their age, both Mr Koh and Mdm Yeoh lamented the move as Rochor Centre provided unparalleled convenience, with the first to third storey of their blocks packed with stores. Unlike Samuel, they don’t feel the pull of nostalgia, since they reason that they have to comply with the decision regardless.

Still, they’re right. What else can you do when your sentimental memories prove to be less valuable than your country’s push for economic progress?

You make full use of the remaining time and try not to think about the end.

“Part of me was happy that attention was brought to the landmark, but I was also kind of sad and slightly angry that people were just coming here to take pictures when it has always been here,” he says.

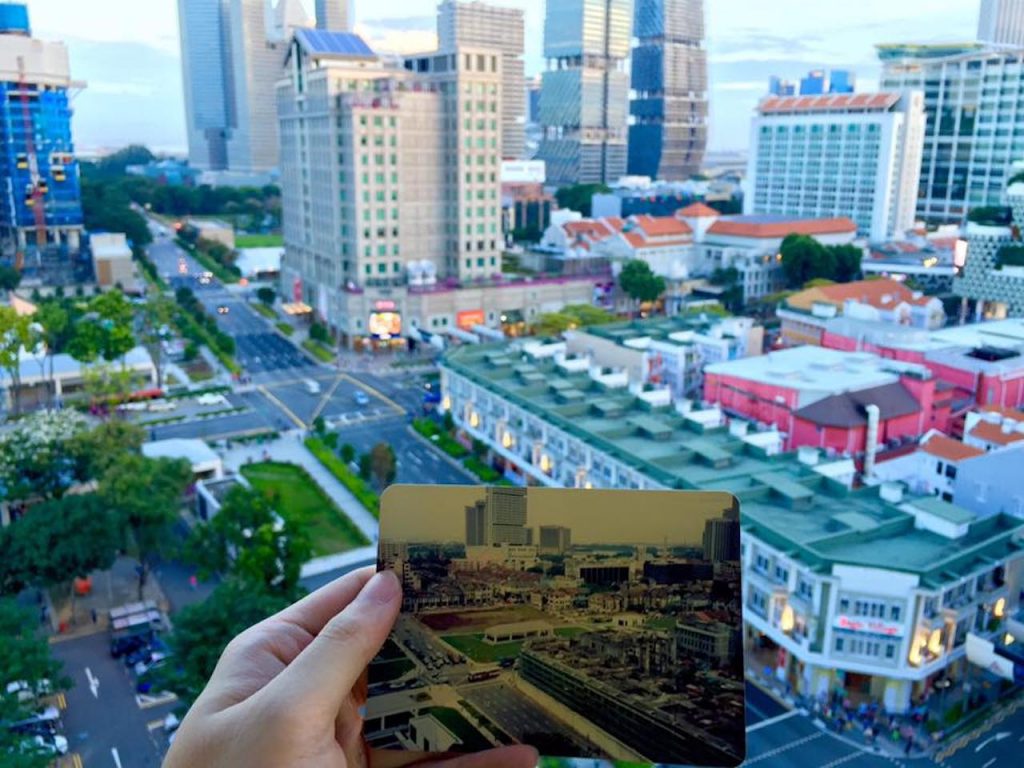

For instance, Samuel used to be able to see Marina Bay Sands from his unit before the South Beach Tower was constructed. His father, who lived in the area when he was younger, saw the construction of Bugis Junction, Suntec City, and the National Library.

“We could also see fireworks when NDP was held at the floating platform. Well, until South Beach was built and blocked it,” he laughs.

While I understand that getting first row tickets to witness the Singapore landscape undergoing massive redevelopment contributed to his memories of Rochor Centre, I sense that Rochor Centre means something deeper to Samuel.

Even as he animatedly expresses his feelings about Rochor Centre, there is an oddly calming presence about him, as though he has weathered a storm.

Then as Samuel pulls up photos of the spectacular view from his unit, which he captured on multiple occasions, he opens up.

There was one point when Samuel was in the hospital for two straight months. Upon his release, he shares that he went home and paused at his lift lobby to take in the view.

“It was really amazing. The view put into perspective what I was fighting for,” he says.

Now a civil engineer with the Land Transport Authority (he joined LTA after graduation to improve the public transport sector), Samuel says that both living at Rochor Centre and contracting cancer inspired him to take up the job.

“As a side effect of chemotherapy, my joints degenerated. I had to go for hip replacement surgery. It was difficult getting around after that, especially going to the National University of Stairs,” he jokes, referencing NUS with a moniker known to many of its students.

In addition, public transport wasn’t as extensive back then, and he found it a hassle to get around with mobility issues.

“If you live at a vantage point for more than 20 years, you see the construction of MRT and rail projects every day. It inspired me to improve the public transport system to make it more accessible,” he explains.

“Public transport is a hot sector, which means there’s a lot of scrutiny. But I do find meaning in my job everyday, and I’m glad I have the opportunity to be there, as cliche as it may sound.”

After hearing his story, however, I understand his reservations. After all, Rochor Centre was an integral part of his recovery from leukemia. Whenever he stepped out of his house, the bird’s eye view of Singapore reminded him of what was worth living for.

As of yesterday, there are no more houses at Rochor Centre.

But for Samuel and other former residents, it will always be home.