In all seriousness, however, the late Yusof Ishak resonates with Singaporeans today in more ways than just being “that money guy”.

Singaporeans are a complicated people. Generally living in material comfort, our lifestyles are also defined by spellbinding technologies and convenient access to knowledge. So how can a man, who had lived decades before this country even paid membership fees to the First-World Club, resonate with contemporary experiences?

In the 1930s, when he was in his twenties, our first President had already set his sights on his own ‘start-up’. At the time, he aspired to establish a newspaper that could be an intellectual medium to modernise the Malay community.

Yusof lived in a world of vast changes that had come with new technologies and the intensification of global capitalism. Many from the working class (Malays and non-Malays alike) were increasingly marginalised in the colonial economy, often due to structural impediments that favoured richer expatriates and immigrants.

Yusof felt that the Malay community should be able to air their responses and grievances. In addition, ideas of self-autonomy and scientific thinking would be promoted through the newspaper.

So, what happens you have a brilliant idea but zero capital?

You launch your own crowdfunding campaign, which is exactly what he did. Yusof and his friends started a daunting search for investors in kampungs and homes, seeking to fund the Utusan Melayu.

His vision was for ordinary folks to be the newspaper’s shareholders—a newspaper for the community, by the community. It sounds rosy with a sprinkle of cheesiness, but just like today, newspapers then were risky ventures when they operated outside conglomerates. They were far from being considered profitable, especially one that was touted as a social enterprise.

As is the norm for start-ups, Yusof did not succeed in his initial attempt.

During World War II, there was a forced takeover by the Japanese, although Yusof nevertheless succeeded in reclaiming the paper and establishing its new office at Queen Street in 1946, a year after the war. He then steered Utusan during the crucial years of decolonisation, during which the newspaper established itself as a prominent platform for the discussion of nationalism and identity politics.

Often, however, it’s this sort of success that brings the shadow of powerful, interested parties. Over time, the newspaper’s shares had been bought over by allies of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), having seen Utusan’s potential as a party mouthpiece.

Initially, Yusof tried to acquiesce. But feeling that his independence was compromised, he decided to call it quits.

Even during the heyday of democratic expression in the 1950s, it wasn’t easy to uphold a fearless sense of journalistic independence while satisfying the demands of your paymasters. Autonomy is a luxury that should never be taken for granted.

But before you think that this article is another story about “innovation”, “entrepreneurship” or whatever catchphrases today’s neoliberal politics may conjure, let me assure you that it is not. Yusof’s calling was at no point straightforward, and his self-finding mission had begun much earlier.

After he could not qualify to be a gazetted officer, a rank usually reserved for royalty, he decided to drop out. He refused to curry any favours, even standing up to a fellow trainee connected to one of the royal families of Malaysia (then British Malaya).

I’m not implicitly applauding his reluctance to “sign on” here, but would instead like to make a point about his attitude towards privilege. Like most Singaporeans today, it would have perhaps been easy to feel jaded when the promise of hard work did not result in success, especially when up against others who enjoyed advantages that came with their circumstances of birth or income.

Of course, the decision to quit a job and search for your life’s calling is in itself a privilege.

At the same time, the class stratification deliberately maintained by the colonial government did not sit well with Yusof. And one can also notice the irony in that he was himself a beneficiary of his own circumstance, having been the son of a top civil servant, which just like today, came with opportunities.

Despite all this, his biographers largely point to this episode at the police academy as the moment when he became ‘woke’, before embracing the fight against inequality and injustice.

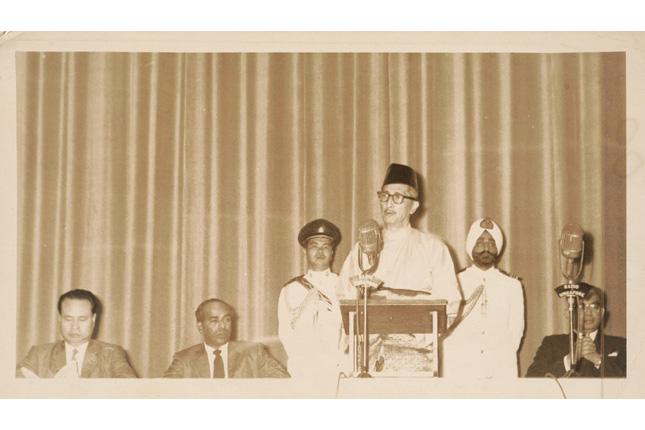

Yusof, taking full advantage of his own privileges, found his sense of purpose in service to the community. After his days preaching social upliftment in the Utusan, he was to be slated as Singapore’s first Malayan-born Head of State.

Of course, we know that the PAP eventually won the elections to form the state government, and so Yusof agreed to come out of retirement to serve.

Yet it is not just this discussion of service and high-minded ideals that have me most enamoured with the man.

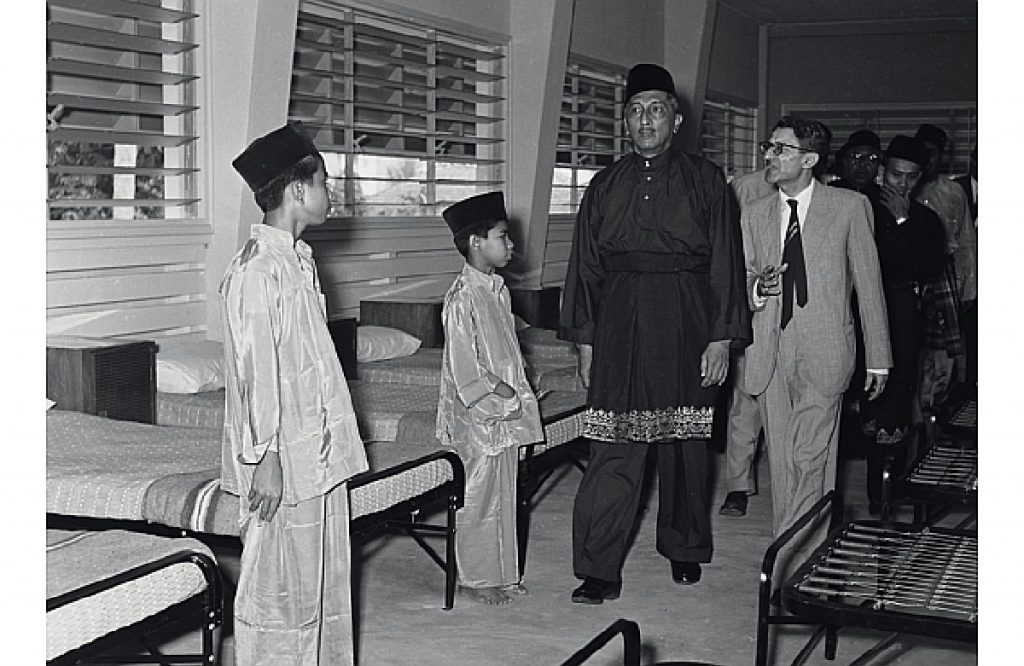

On a much more personal level, Yusof was an adrenaline junkie through and through. He loved sports and the outdoors as a young man and continued to promote them while in public office (he was once a boxing champion). Although far from being a sportsman myself, I’m reminded that today we seek pleasure in many ways—indoors or outdoors, online or offline. And Yusof’s story reminds us that it’s not a bad thing to take part in your own thrills.

Speaking of thrills, it wouldn’t hurt to mention that in his anger following the episode at the police academy, Yusof experienced a moment of YOLO, embarking on a speeding trip on his motorcycle. He cruised through his journey from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore in less than 3 hours; bear in mind, there were no modern expressways then.

Perhaps his penchant for blatant badassery explains why he was also known to be quite a prick of a boss while at Utusan, throwing tantrums and taking it out on his employees.

Today, we honour his legacy. But instead of naming people after orchids, we name orchids after people as part of our affable gestures in diplomacy.

Yusof was also unafraid to show his sentimental side, with photography being one of his more passionate hobbies. After his death, his family donated thousands of pictures from his personal collection to the archives. I don’t think he took selfies, but any search for his pictures in the archives will showcase occasional images of him with his camera.

At this point, you may wonder: what’s the point of all these biographical nuggets about Yusof Ishak?

There was no social media during Yusof’s lifetime, but even so, he did not leave behind a memoir to remind people about how important he was.

Following his death in 1970, the telling of his story has been based on the historical traces of his life, and on the memories of those close to him.

Yusof was nevertheless still respected and loved by Singaporeans whom he served, long before others wrote biographies about him and before he became immortalised on our dollar notes. While he did not need to worry about elections as a ceremonial Head of State, his story makes an important point about connecting with ordinary Singaporeans.

Contradictory as it may sound, I wonder if public figures could be more relatable should they stop being so public about themselves. A silent peace towards their own habits, strengths, and failures could be a dignified exercise in self-respect and genuineness, as demonstrated by Yusof Ishak. There is no need to make painful, noisy attempts to remind others of one’s beat-up Toyota or Casio watch to prove that one is down-to-earth.

Humanising yourself does not need to come with awkward in-your-face interjections about how much of an ordinary Singaporean you are. Otherwise, we could end up in a situation of playing a mocking caricature of the ordinary Singaporean rather than being truly relatable or empathetic.

Finally, it is indeed problematic if we excessively look to the past to satisfy a longing for visionary leaders who not only inspire but also resonate with us. A need to indulge this guilty pleasure, however, also reveals that much is to be desired in the present.