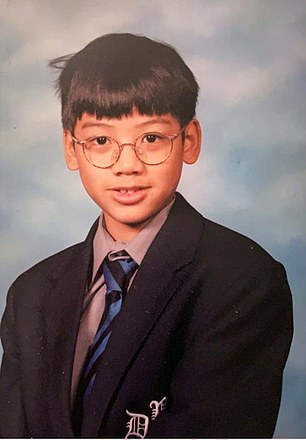

Top image: Mixmag Asia

This article was first published 15 Jan 2019.

Londoners picking up their Daily Mail back in 2019 were greeted by this glaring headline: “British ex-public schoolboy [sentenced] to barbaric 24 strokes of the cane”. The article refers to the case of British 29-year-old Ye Ming Yuen, a former Zouk DJ who was charged in Singapore with committing repeated drug offences back in 2016. Ye was then sentenced to 20 years in prison and 24 strokes of the cane.

In the Daily Mail article, several phrases leap off the page: “bare buttocks”, “stripped naked and strapped to a trestle”, and “flogged”. These phrases are not quotes or citations from other sources; they are injections from the author, journalist Stephen Wright, who recently won the prestigious Paul Foot award for campaign journalism.

There is little doubt as to why he used such evocative imagery. The visual language conveys the physical and inhuman nature of the punishment. Despite the description, an online commenter said with reference to the caning, “Not much to fear. Reminds me of school.”

The comment has currently over five hundred upvotes.

To many, the cane is an old friend, introduced to them in childhood at the hands of a teacher or parent. Stick thin, bone white, we feared its name and cringed when we heard the whiplash crack of its swing. The association between the word ‘cane’ and that coloured handle (blue, in my case) has quite literally been beaten into us.

As we’ve grown up, we’ve learnt about the criminal justice system, imprisonment, caning. We’ve read about high profile cases involving foreigners like Michael Fay or Oliver Fricker. Every time the debate around this punishment erupts, over and over we hear its name: caning, caning, caning.

Judicial Corporal Punishment (JCP), to use the legal term, has been around since time immemorial. In Singapore, corporal punishment is spelled out in the Straits Settlements Penal Code of 1871, detailing whipping as a punishment for robbery, assault, and rape.

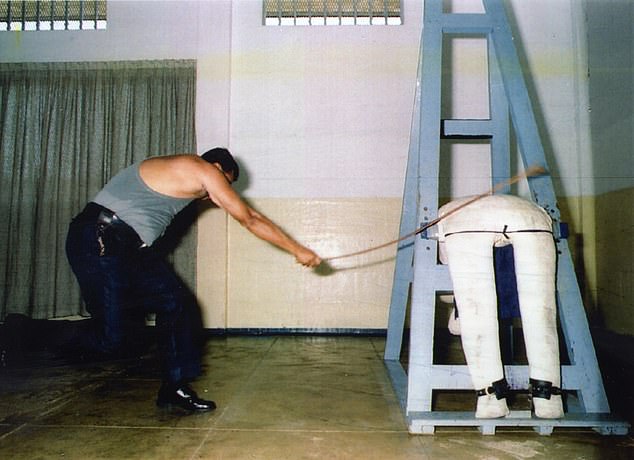

While ‘whipping’ historically referred to being struck across the shoulder blades, it was increasingly phased out in favour of strapping or birching, which meant to strike the bottom with a stiff rod or leather implement. The offender may have been held with a British prison flogging frame; a similar variant is used to cane offenders today.

After WWII, the Singapore Criminal Justice Ordinance of 1954 clarified that JCP can only be inflicted using ‘strokes of a rattan’. Subsequent amendments post-independence now refer to the punishment as caning, ‘cane’ being a direct translation of the Malay ‘rattan’.

Today, we understand that JCP caning, performed by a burly corrections officer using his whole body to swing a 1.3cm rattan stick, differs greatly from the household variety, usually done with a (tired) parent’s flick of the arm.

Most of us have seen—or pictured—the bloody wounds it inflicts on offenders subjected to it. We have heard accounts of how excruciatingly painful it is. We are consciously aware of all these distinguishing details and yet, subconsciously, if someone mentions caning, the first image that comes to mind is that blue handle. The first sound is that thin hiss, and the first sensory response is that sharp sting I can almost feel on my palm.

Making caning palatable

For many people, the word ‘caning’ holds a similar dual meaning.

What we’re engaging in—to borrow a term from George Orwell’s 1984—is a bit of subconscious doublethink. Doublethink involves holding two contrasting ideas, “knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them”.

In 1984, this system is used to explain the the nation of Oceania’s perpetual war. Oceania is allied with Eurasia, a neighbouring state, but one day, a news bulletin in Oceania reports that the two countries are now and have always been at war. The citizens know that only yesterday Oceania was in an alliance with Eurasia, but are simultaneously able to accept the contradictory claim made today, that the two nations have been natural enemies since time immemorial.

While our doublethink is nowhere as overt or exaggerated, in the issue of caning, it similarly negates the effects of opposing ideas, resolving the conflict without actually coming to a productive solution or compromise.

In other words, we know that criminal caning is horrendously painful, which justifies our argument on how it serves as a deterrent. Yet we most strongly associate ‘caning’ with the small, insignificant stings that we received as children, subliminally downplaying the suffering involved in JCP. In this way, we more readily accept its existence.

Granted, it’s a strange issue to unravel, and one that leads to some cognitive dissonance in trying to reconcile these two ideas.

While the associations of JCP to our childhood punishment are subconscious at best, political supporters of caning often take advantage of this in a very conscious way. Lee Kuan Yew famously referred to getting caned thrice by a corrections officer as “three of the best”—the exact same phrase he used when he described being caned over his clothes by the principal of Raffles Institution when he was a student there.

While one can only speculate on the subconscious association LKY himself had between JCP and that childhood caning, there’s no doubt that ‘three of the best’ was used to draw a link between the two experiences. This diminished the severity of JCP in the eyes of the general public, and perhaps the international community, rendering it more palatable.

The doublethink subconsciously encoded in the word ‘caning’ was used consciously to obscure JCP with the veil of harmless childhood caning. This calls to mind another Orwellian term: doublespeak, which is to say one thing and mean another.

Using language to implicitly diminish the severity of suffering, while touting the deterrent value of that severe suffering, is inherently contradictory. Offenders subjected to this punishment are not children fearing a spanking, they are adult men being beaten until they struggle and bleed.

Such diminishing language muddies the water and hinders any well-informed debate on the issue. So how do we solve this linguistic conundrum?

Repackaging linguistically

My proposal is simple. We need to alter the key term used in this debate: caning.

‘Flogging’ is perhaps too extreme. It was often performed on the upper back and in a public setting, where offenders were simply tied to a pole and struck with a cat-o-nine-tails, a knotted rope weapon that tore the flesh from its victims.

Another alternative is birching, so named because it most commonly used twigs of the birch tree. Several twigs (more akin to sticks or branches) were tied together and used to beat the buttocks of an errant prisoner or schoolboy. However, on top of being incredibly archaic, the practice used a stiff rod as opposed to the pliant and flexible wet rattan used in the Singapore penal system.

To find the most appropriate term, one must return to the old Straits penal code and its description of ‘whipping’.

In modern Singapore, the ‘rotan’ used by the corrections officer is a rattan stick soaked in water until it is as bendable as a leather whip. While one might object to the negative connotation of ‘whipping’ as opposed to ‘caning’, I would argue that this connotation in fact conveys the true pain and level of suffering of a criminal caning—something that its proponents should not run from, especially since it is a key aspect of the deterrence argument.

Across the causeway, the term ‘whipping’ has been retained as an official description of the punishment. I can’t help but note that Malaysia has seen spirited challenges to JCP, most notably in the Malaysian Bar’s denouncement of the punishment as cruel and inhumane. In Singapore, however, public opinion seems firmly for caning, and an appeal to ban it was denied in court. The only difference between JCP in the two countries is that in Malaysia, the offender is upright; in all other respects, the punishment is identical.

One has to wonder if the difference in attitude has been shaped by the different term each country uses to label its use of JCP; if Malaysia’s more accurate description has made the Malaysian public more cognisant of the true nature of that punishment.

While whipping might be the issue highlighted in this article, we should regard doublethink on any subject with equal importance. The only guard against this is to question the source of your beliefs. It is perfectly possible to hold two contrasting opinions, if you analyse the logic behind your arguments and understand how personal biases affect your views.

Accordingly, the only guard against disingenuous doublespeak in public discourse is to question the intentions and agenda of those speaking, and analyse the truth behind their language.

Therapy is a science. ‘Conversion therapy’ is quack mysticism propped up by conservative ideology.

Interrogation is questioning. An ‘enhanced interrogation technique’ is waterboarding a man to get a false confession.

‘Caning’ is disciplining a child. ‘Judicial caning’ is whipping a man with a bendy stick until he can’t sit down for a month.

We can only debate and come to an agreement on issues if we are operating in the same, logical reality. So let’s not dance around the nature of JCP, nor say that it “reminds us of school”. The reality is that they are nothing alike.

Whipping is an ongoing, painful punishment in our criminal justice system, and an issue that overlaps with serious questions about who we are as a society, and who we want to be. Only when we assign it a proper name can we begin to talk about it.

*A great deal of information on the history and modern application of corporal punishment, including its use in Singapore, is available on the World Corporal Punishment Research website, a free online repository of corporal punishment facts collected by independent researcher C. Farrell.