When Heng Swee Keat was ‘confirmed’ as the PM-in-waiting last month, many Singaporeans breathed a sigh of relief.

Some were glad to see an experienced Finance Minister at the helm, whilst others were disappointed at the lack of Tharman. Most citizens, however, simply closed their eyes and said a silent prayer of gratitude: “Thank god it’s not Chan Chun Sing.”

Okay, I lied. The prayers were loud and gleeful. Many were overjoyed to learn that Chan Chun Sing, long considered the frontrunner, would not be our next King. They were so ecstatic that the usual ‘return my CPF’ complaints were temporarily suspended, replaced by expressions of schadenfreude at Keechiu’s ‘downfall’.

Personally, I don’t like CCS, but I’m also disturbed by the amount of hate that he has received over the past year. To me, he is just another 4G Minister like his peers OYK and TCJ, neither exceptional in his achievements nor particularly damning in his faults.

So what gives? Why do so many people have such a deep-seated dislike of Keechiu?

The Boy Who Lived

The most obvious answer: people don’t like his face.

Don’t roll your eyes, because you know it’s true. Some politicians are blessed with an authoritative jawline (Macron). Others, with a kindly disposition that reminds you of a well-loved uncle (Tharman).

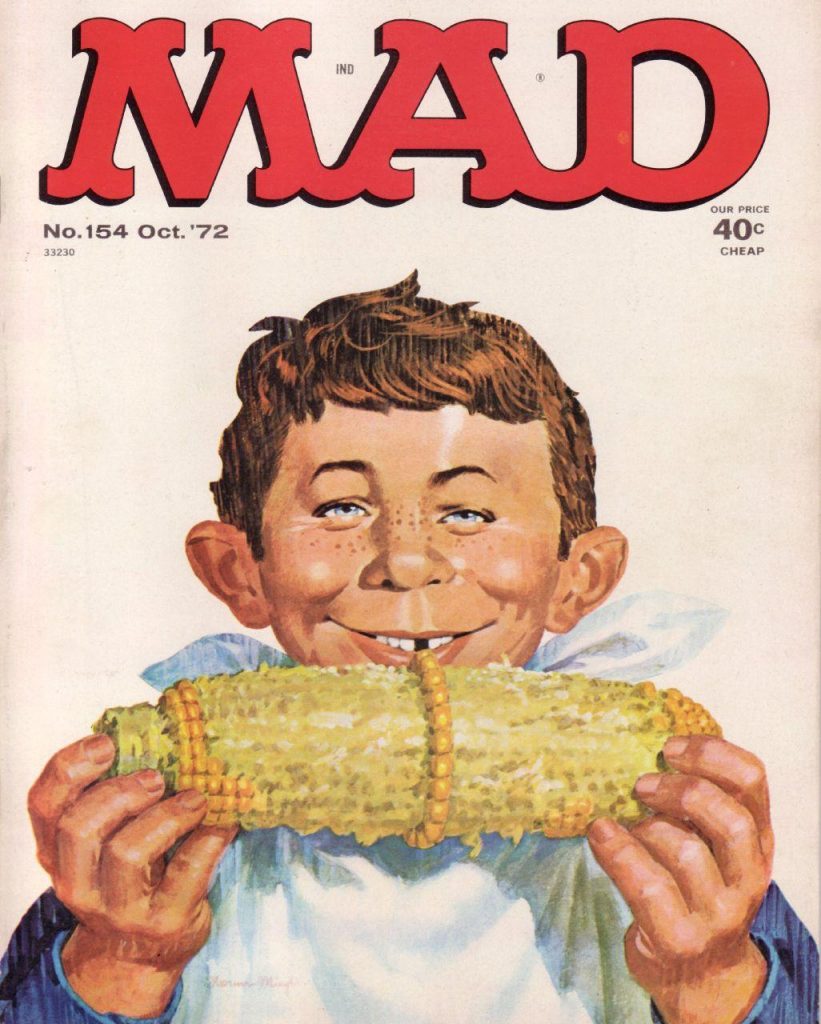

CCS, however, looks like a boy. Specifically, the boy from the cover of MAD magazine. The large ears, buck teeth, and moon face make him look like a venture scout cosplaying as a Minister, and prevents him from projecting the gravitas that voters expect.

And it gets worse when he’s not smiling for the camera. At rest, his mouth curls naturally into a smirk, twisting his boyish features into a picture of smugness.

The unfortunate geometry of his head is not helped by his manner of speaking, which is neither heartland nor RI.

A Singaporean politician has 2 choices when making a speech: either speak like Low Thia Khiang and sound like a man-of-the-people, or speak like Tan Chuan-Jin and sound like a proper Oxbridge-educated elite.

There are pros and cons to both, but CCS seems incapable of either. If you watch his public speeches closely, there is an odd note of inauthenticity when he speaks. When he’s talking to ‘the people‘, the Singlish accent seems exaggerated, and you get the feeling that he’s pandering or being condescending. When he’s speaking to his peers at a conference or in parliament, the intonation is a little weird, and he sounds like a man struggling to keep the Singlish from creeping into his Queen’s English.

The result is a neither-here-nor-there accent that confuses everyone. He doesn’t sound like one of us, or one of them. He sounds like … a person trying to sound like someone else. Not a good look for politics, where sincerity is a valuable currency.

Ugly Delicious?

The optics are bad, but bad optics have never killed a career in Singapore. Ex-Minister Lim Swee Say was no more eloquent and Khaw Boon Wan was well-respected before being thrust into the SMRT crisis, despite his uncanny resemblance to a notable local thespian.

Instead, I think the reasons for CCS’s unpopularity go much deeper than looks or voice. His unlikability tells us less about him and more about us; our unconscious values and the expectations we have of how people in authority ought to behave.

To start with, cast your eyes back to 2015, before SMRT’s Annus Horribilis and the PAP succession challenge, to a time when Keechiu was just one Minister amongst many and not The Chosen One.

The responses were remarkably different back then. Instead of merciless scorn, many praised him for his humility, hard work, and ability to understand ordinary Singaporeans. Words like ‘humble’, ‘down-to-earth’ and ‘Army Casio Watch!!’ appeared often and without irony.

So what happened?

The first hurdle came in the form of train breakdowns. Although it was not CCS’s department, the SMRT crisis of 2016 onwards tarnished the reputations of scholar-generals everywhere. As breakdowns continued to occur under the watch of ex-General/SMRT CEO Desmond Kuek and ex-admiral/LTA chief Chew Men Leong, everyone started to question the ability of high-ranking SAF personnel who were ‘parachuted’ into civilian roles.

Having trod the well-worn path from Scholar to General to Minister, Keechiu could not escape the backlash. He is the poster-boy of the PAP’s ‘meritocratic’ system, but in a time when Singapore was starting to challenge received ideas of what constitutes ‘merit’.

Unfortunate, but hardly fatal. But what really killed his popularity was, ironically, his ascent as a possible PM candidate in 2017.

If you recall, it was the time when Tan Chuan-Jin was nominated to replace Speaker Halimah Yacob, and the PM marathon became a ‘3-horse’ race between Heng Swee Keat, Ong Ye Kung, and CCS.

Of the three, CCS emerged as the most vocal. Around late last year, he appeared often in the media, to weigh in on ‘issues’ of the day—ranging from the controversy of President Halimah Yacob’s walkover election to the challenges faced by each generation of Singaporean leaders. He made many statements on Very Serious Subjects, often not related to his portfolio .

But the more he spoke, the less everyone liked him. Talk of humility soon turned to ambition and he became widely seen as someone grasping for power and too eager for the PM’s throne. His pompous speeches about what a leader should be were often mocked as ‘wayang’ and ‘sing song’—noise from a man who is all talk and no action.

The tone of his statements probably didn’t help either. Most of his statements were lectures on challenges in the near-future, and arrogance was unavoidable when he spoke on behalf of ‘Singaporeans’, telling them they ‘need to understand the region better’, or ‘why leadership continuity must be the way forward’.

In his defence, speaking to the media and laying out a vision of the future is part and parcel of every politician’s job. American Senators and British MPs do it all the time. In Singapore however, speechmaking is often equated to wayang and we are skeptical of public figures who appear too often on our newsfeed. Talk is not considered a prelude to action but its opposite; an attempt to avoid ‘real’ action.

That’s why one of the most common criticisms of CCS is, “What have you achieved since entering politics?”

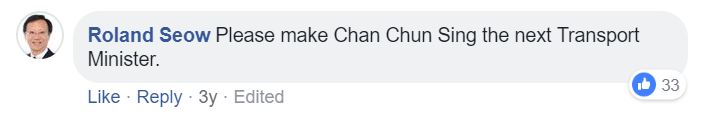

Or more bluntly: “Talk so much why don’t you go and take over the Transport Ministry and fix SMRT?”

This distrust of those who seek power or readily push themselves to the fore is a deeply Singaporean sentiment. In Asia, power must be thrust upon an unwilling victim and not sought out for its own sake. A leader must be a humble servant first, and a visionary second. You must talk about what you’ve already done and not what you intend to do, because this is no country for wannabe Barack Obamas.

Unfortunately for CCS, silence is a luxury future-PMs cannot afford. He needs to articulate his ideas on the issues that matter if he wishes to be taken seriously as a leader, but he cannot do so without raising the ire of an audience who frowns upon such ‘politicking’.

You can also see this philosophy reflected in the rhetoric around Heng Swee Keat. Where CCS is called a wayang, HSK is praised for his quiet, careful demeanour, his experience, his low profile, and above all, his humility, all of which make him a ‘safe pair of hands for Singapore’. Although he speaks less often, it actually works in his favour because it creates an aura of modest virtue. In short, he is every model student who works hard and speaks only when spoken to, an ideal exemplar of what an ‘Asian’ (Chinese, really) Minister should be.

This is the Keechiu Paradox. To be seen as a 4G Leader, he must keechiu and speak his mind on important challenges facing Singapore. If he does, however, he will be perceived as speaking out of turn because he lacks the experience and seniority to do so.

It’s easy to hate on Chan Chun Sing, but much harder to pinpoint why we single him out in a crop of 4G leaders who are more alike than different.

Policy or ideology-wise, there probably isn’t much difference under the PAP’s style of collective leadership. And as for character, it is impossible to separate a politician from his public persona.

So, in the end, our dislike of CCS does not really tell us anything insightful about him. It does, however, shed light on our own biases and what we demand of our politicians. Our hatred speaks volumes about our disdain for American-style sloganeering and about how conservative our values truly are.

For all the talk about westernisation, we expect our Ministers to be mandarins — humble, low-key and unassuming. We respect seniority and experience in figures like Tharman and HSK, even if we do not agree with the policies they’ve forged.

That, of course, leaves CCS in a bind. He doesn’t have enough time to become a Tharman but the job requires that he step up, and hold forth on the public stage. A leader must speak but Singaporeans have little time for those who speak when it’s not their turn.

Leadership truly is a burden, is it not? Hands up if you agree.