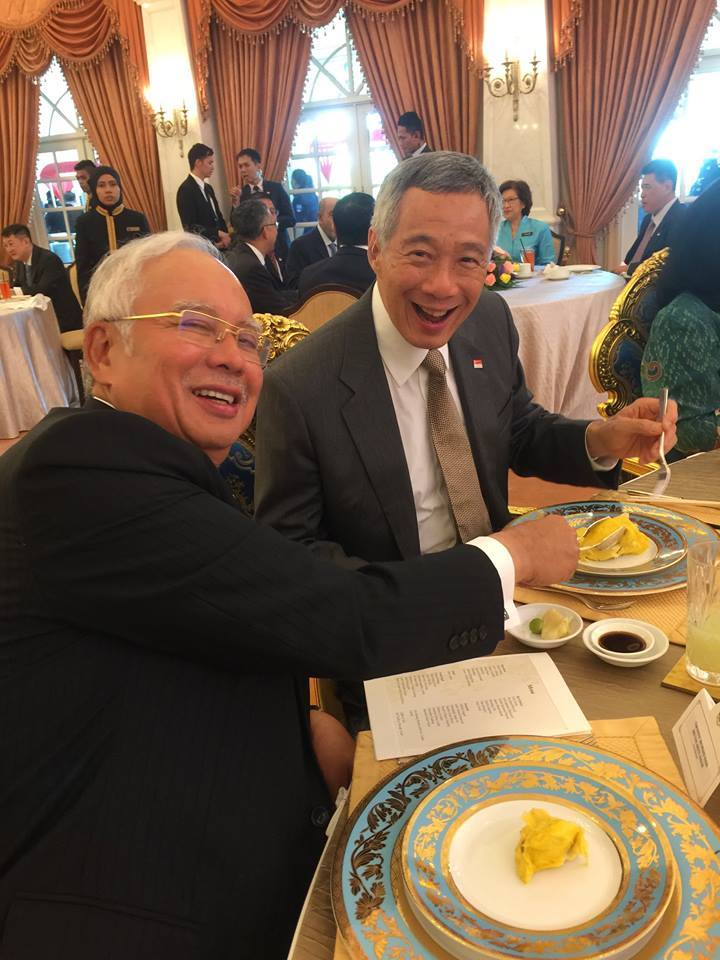

No matter the flavour, every Singaporean politician knows that the hawker centre walk-around (and obligatory subsequent Facebook mobile upload) is a staple of the political landscape. In a country so famed for its food, chatting with Singaporeans about bread-and-butter issues over their morning bread and butter does seem like an excellent way to connect with their constituents.

From the ‘candid’ shots of Minister for Defence Ng Eng Hen, grinning eagerly at a young boy as his father looks on with “Don’t-say-something-stupid-ah-boy” plastered on his face, to the grainy photos of Crown Prince Heng Swee Keat, dining with elderly constituents as one gentleman prepares to eviscerate his sandwich; politicians will often chow down to get that coveted #relatable factor tagged to their public image.

However, politicians are in reality an elite social and financial class. While everyone agrees that kopi-O and kaya toast make the best breakfast, there is something extremely patronising about the powerful wielding photos of hawker centres for the express purpose of appearing relatable and down-to-earth.

When Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made his local debut for last year’s ASEAN Summit, he decided to take 5 for a pit stop at the iconic Adam Road Food Centre, while sipping some lime juice of all things. As we see him chat up the locals, one can’t help but feel a dead weight slide into their gut, and not just because of the four prata kosong I walloped for lunch.

Trudeau’s smiling face, the snazzy camera angles, the ready-made Straits Times headline; a lurching sensation grips us, as though we’ve fallen headfirst into Uncanny Valley.

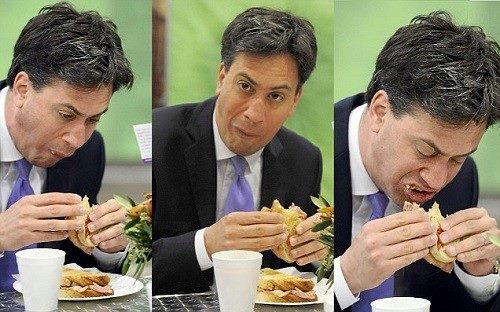

Miliband’s rival, David Cameron, won the election; Cameron held a referendum on staying in the EU, and voters spanked him out of office by deciding to Leave. The sandwich has since been bandied about as the bacon that began Brexit.

What’s not human, however, is dissecting a hot dog with a knife and fork, the way the Cameron-3000 decided to, in an ill-fated attempt to avoid Miliband’s blunder.

At least Miliband’s gaffe was relatable; David Cameron fell squarely into uncanny valley, failing his programming parameters.

We celebrate Michelin-recognised hawker stalls, and we enjoy the same hawker food every day of the week. Food is something deeply private, familiar, intimate; we connect emotionally to food like no other inanimate object. It fills us, warms us, nourishes us. It’s only natural that we feel a little strange seeing politicians eating the same food we put in our bodies. This conflation of the deeply familiar with the recognisably unfamiliar doesn’t sit well, and we’re left staggering around uncanny valley.

Common Singaporeans rely on hawker food for cheap and easy meals, especially those who cannot afford otherwise. And sure, politicians are not excluded from enjoying hawker fare. But to then use that food to say, “Look! I’m just like you,” when our circumstances differ greatly, can come across as insulting to the intelligence of average Singaporeans.

However, there is hope for the political class. While scrolling through the instagram profile of Minister Shanmugam, who provided the inciting photograph for this tirade of an article, I chanced upon another photo: familiar, friendly, even fraternal.

Food, unlike politics, is deeply human. And when politicians eat, it can be transformed into something strange, something uncanny, or even something shameful (RIP Miliband). Photo ops don’t bother us because they’re politicians. They bother us because they’re impersonal, and we see right through their efforts at pandering.

We share a common food, not a common rice bowl; using food photos as a tool to insinuate otherwise is disingenuous.

Or perhaps I’m wrong.

Maybe the real reason we hate political food photo shoots is because we secretly fear the same fate will befall us. That we’ll take a seat at our favourite hawker centre, ready to plunder a bowl of wanton mee, only to be interrupted by our local MP, delaying the satisfaction of enjoying that object of our most primal desire: food.