Special thanks to Terence Heng, Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Liverpool, and Victor Yue, without whom this story would not have been possible.

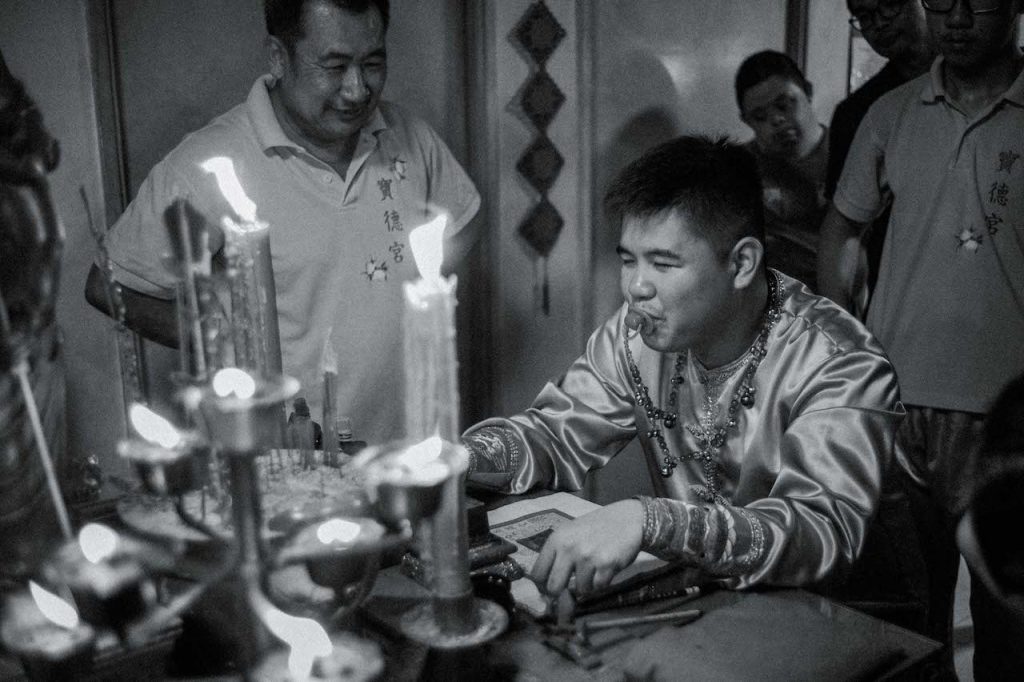

After being invited to partake in bā gē’s favourite habit, I am told to sit in front of him. He offers me a cup of bitter Chinese tea followed by a cup of a much sweeter one. As I sip from the second cup, he drinks the bitter one, before croaking poetically in Hokkien, “I’m drinking the bitterness for you, so you can have the sweetness.”

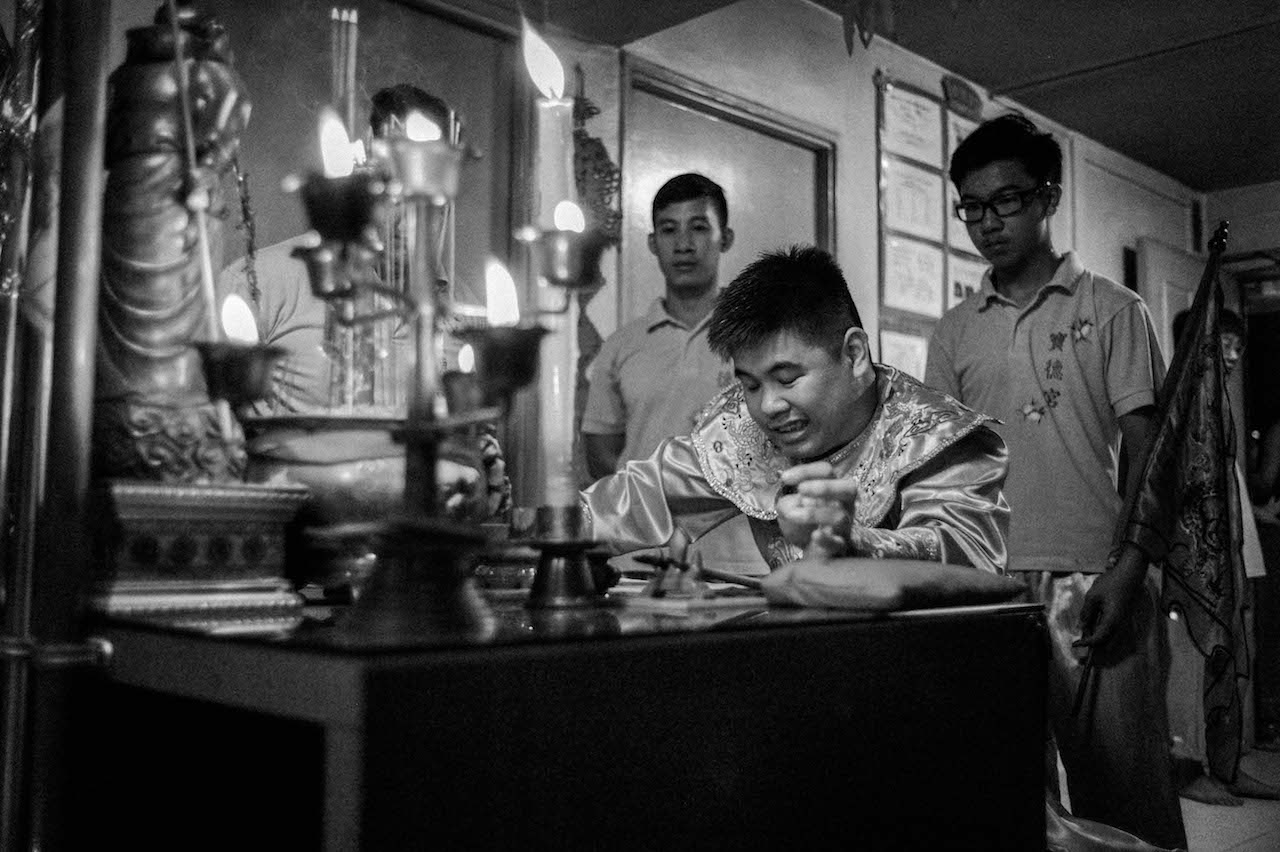

What surprises me isn’t so much that Nick, the spirit medium whose home-based temple I’m visiting, is dressed in traditional imperial-looking garb that I’ve only ever encountered in a Chinese opera performance. Instead, it’s the fact that he seems genuinely transformed—which immediately negates any initial scepticism I might have had.

Every Friday, like clockwork, he holds consultation sessions at his family home in Ayer Rajah. Each session is split into two parts. During the first, he channels Monkey God; in the second, he channels a hell deity named bā gē.

Both deities have distinctly different personalities, and devotees visit them for different reasons.

“People like to come to see Monkey God for health reasons, and bā gē is more for luck and for communicating with the afterlife,” Nick later tells me.

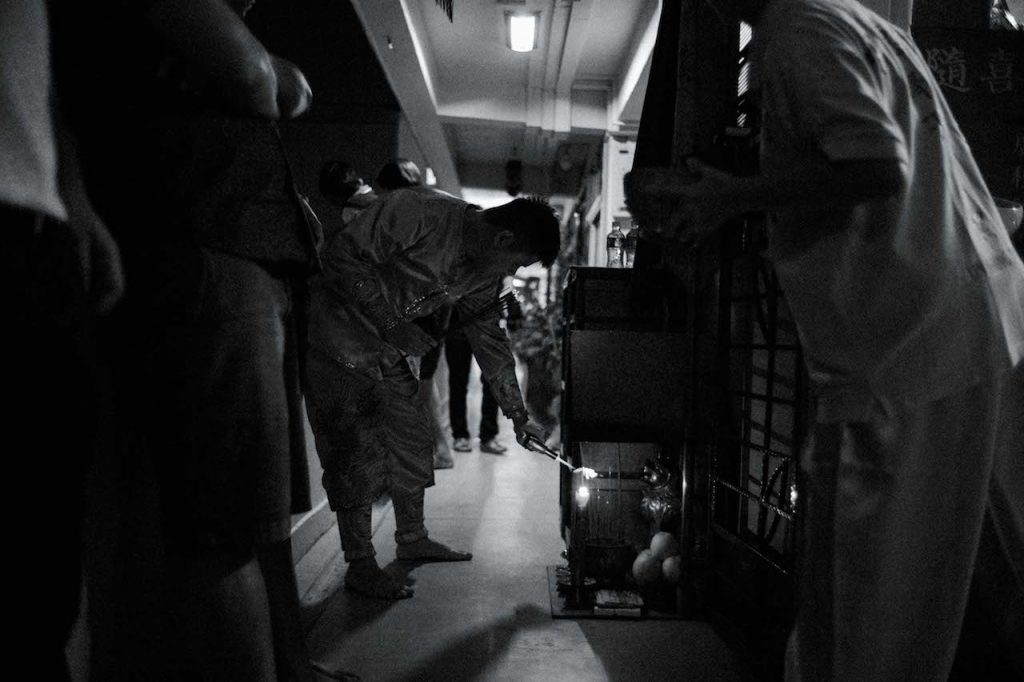

By the time the session is over, it is 12:15 AM, and I smell like a barbecue pit. With incense smoke clinging to my skin and hair, it feels like I’ve been through a cleansing ritual of otherworldly proportions.

Many sîn túas in Singapore have been around for over 30 years, but the particular one I’m at is just over 4-years old. Unlike most mediums who are in their 40s and 50s, and who tend to be heavily tattooed blue-collar workers, Thng Fu Jie, or Nick, is only 29 this year. He’s also an insurance agent.

While his youth seems encouraging given how Taoism is slowly losing popularity with Singapore’s younger generation, Nick shares with me his belief that his generation of mediums will most likely be the last.

“Not only is it not easy,” he says, “But you must also do it because you really want to help people.”

For every generation of mediums, he explains, the next generation “will grow smaller by half”. This is due to the various challenges that sîn túas are facing today.

To begin with, there are too many devotees who look to the deities for all the wrong reasons. According to Nick, 7 out of 10 of those who visit mediums are there for something related to luck. Either they’re hoping to win at the lottery, or they’re hoping that something can be done to make their lives better (or richer).

In a way, this has resulted in the proliferation of a particular kind of performance-based medium. These guys, Nick shares, only channel the gods when they are engaged to do so. As though this doesn’t sound suspect enough, many of these mediums have rates for performing specific acts.

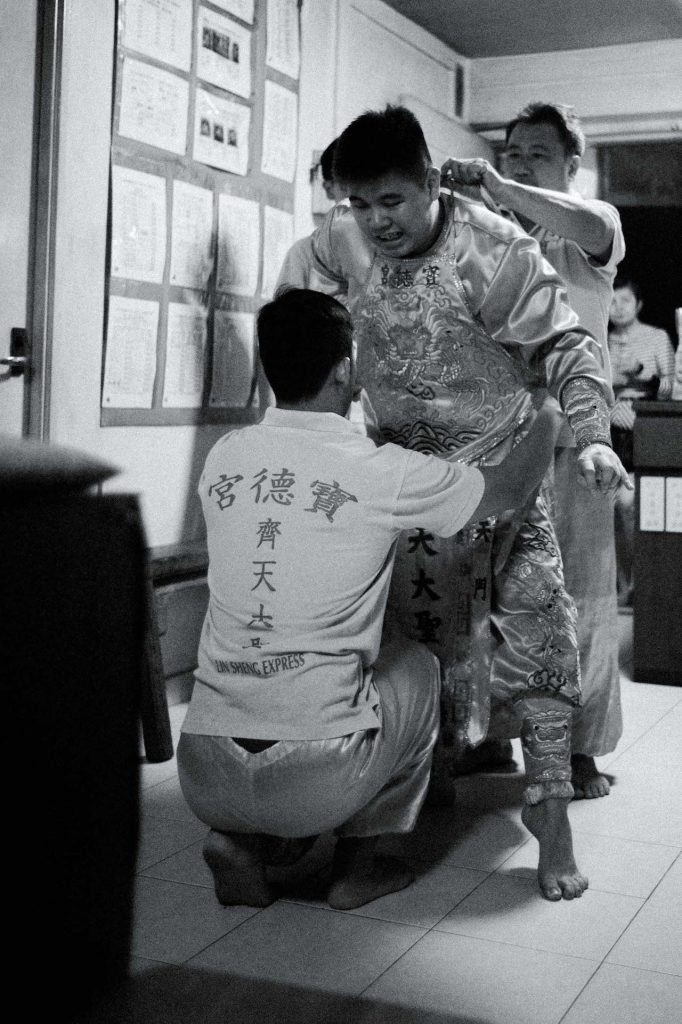

For instance, when mediums channel the gods, it’s commonplace for them to perform certain kinds of “superhuman” feats. This ranges from slicing their tongues to the point of bleeding to piercing their bodies.

With these performance-based mediums, every act is compensated accordingly. As Nick puts it, “Pierce arm one price, pierce body another price.”

They’re also mostly only interested in entertaining those who have hired them, which isn’t how all this is supposed to work.

When I ask Nick whether these guys are the real deal, he replies, “Not say not real la. These things are always real. But how you use it, that’s between you and the deities.”

“Mediums are dead, actually,” he says, emphasising that as a human being, he isn’t actually worthy of anything when not channeling a deity. At the same time, there are devotees who still choose to venerate these mediums even when they’re not in a trance. Consequently, mediums have been known to exploit this reverence.

Nick explains, “A lot of sîn túa have closed over the years. And when a sîn túa close, there’s only one of four reasons why. Number one, money. Two, fame. Three, women. Last, rumours, or gossip.”

As a result, the first “case” that Nick was given saw him travelling to Malaysia to investigate a residence that had been unable to secure a tenant. Upon reaching the apartment, Nick says that he saw “a lot of things flying around”—restless spirits that needed to be appeased.

“I went with another priest, but when I went inside the house, I turned around and saw that wah lao eh, he was still outside and he let me come in by myself. I had to shout at him, come in la! And then we just performed all the necessary rituals, told the spirits the house now belonged to someone else, and so on.”

Shortly after Nick returned to Singapore, the owner of the apartment found a tenant.

Stories like these sound almost like miracles, but they are also prolific, and every devotee from Nick’s sîn túa has their own to tell. There is the one about the devotee who, thanks to bā gē, won first prize at the lottery 3 times in a row, netting him enough money to afford his wife’s hospital bills.

Then there is the one about the devotee who had a complaint about an antagonistic supervisor at work. In response, bā gē gave him a choice: “More work but a less irritating manager, or less work with no change in the manager’s behaviour?”

Upon picking the former, the devotee is now knee-deep in work, running an entire procurement department on his own. As for his supervisor, the man was transferred elsewhere shortly after the consultation session.

54-year old Philip Thng, Nick’s father, tells me, “When Monkey God first came, Nick was sleeping and we were in the other room. When I heard it, I quickly ran in, and I told him he had to wait; let Nick finish school and NS first.”

He also says that he wasn’t surprised that the Taoist deities had chosen his son. After all, both him and his father had also been called by the deities in the past.

To outsiders, the origin story of Nick’s mediumship can sound like the stuff of movies. He shares that it was during a friend’s wedding when the Monkey God was finally done waiting and paid him a second visit.

“I only had 2 glasses of wine, so confirm I was not drunk. But we were all in the hotel room after the dinner when Monkey God came. Luckily all of my friends are used to this kind of thing, and actually one of the guys there was a medium also.

“After Monkey God possessed me, it possessed him, and through him, he told me it was time to start. So that’s how I knew.”

That same evening, I watched as a devotee took her 38-year old, mentally challenged son through the basic rituals of worship, lighting joss sticks with him before sitting him down in a corner of the flat while she consulted with the Monkey God.

Just the week before, she had come alone, seeking advice on whether she should buy him a smartphone. Worried about the possibility of addiction, she was equally helpless whenever he would just use his father’s, getting upset whenever the smartphone was withheld.

She was clearly distraught, yet bā gē proceeded to crack a few jokes before asking the other devotees in the room what they thought. Unanimously, everyone agreed that she should just give him what he wanted.

As she sighed with relief, it was as though a invisible weight was lifted from the room.

For many of Singapore’s non-formally educated elderly, the sîn túa is a space in which they can bare their souls. Here, they too are worthy of an audience with the divine, never mind who they are or where they’re from. More than just a source of practical advice, it is also therapy.

As such, Singapore’s sîn túas exist really to allow ordinary folk to create their own heartland communities. It’s not about luck or statues, they tell me. Instead, it’s about guidance and support.

Nick adds, “The deities are not your servants, so you must have the right mindset. Some people keep jumping from one sîn túa to another just because they don’t get what they want. This one don’t give them strike 4D so they go to the next one. I tell you, the deities see also sian. One day, they will stop coming.”