Curiosity gets the better of me, and I approach him to strike up a conversation.

His name is Goh Soon Kiang, and he is 70 years old. Friends called him Ah Goh. It doesn’t take him long to warm up, and as we talk, I find myself engrossed by the stories of his life.

Eventually, he invites me to his home.

There’s a silent melancholy to the place, punctuated by the distant rumble of urban life and the occasional train.

I wait as Ah Goh finishes with the household chores, which he does himself every day.

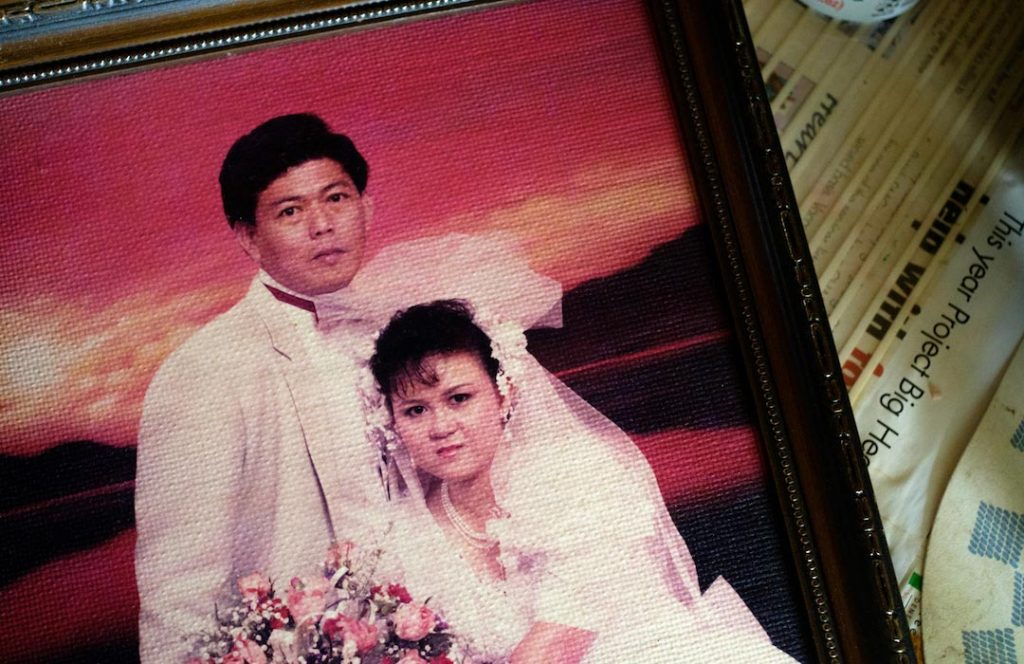

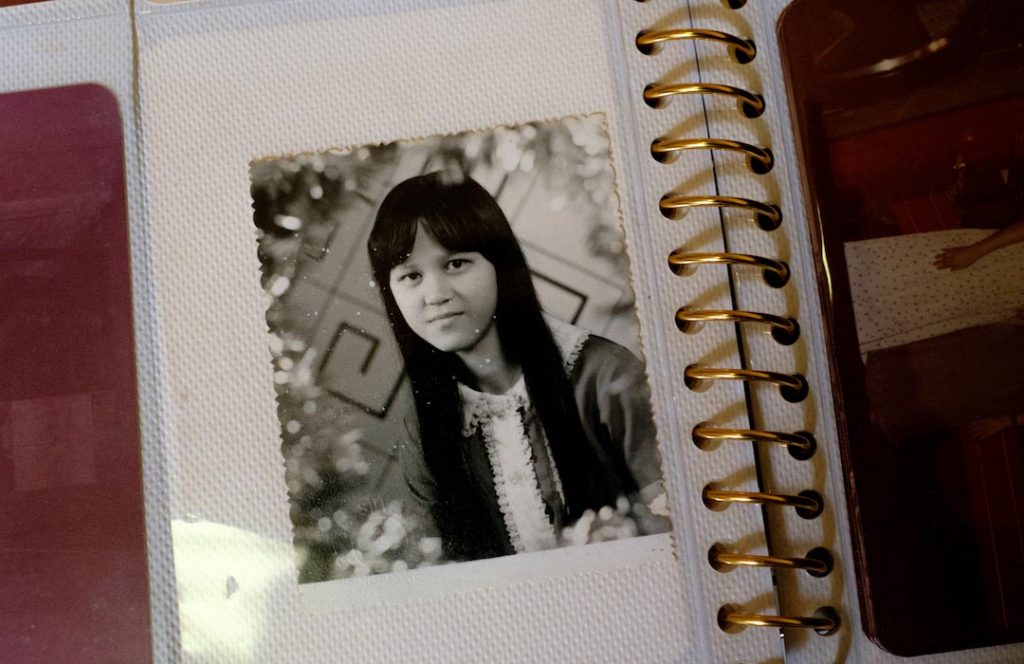

The household chores were once taken care of by his wife, Madam Ong Kim Suan. Ah Goh affectionately describes her as an intelligent woman with long, beautiful, flowing hair. He reminisces about the touch of her skin, fair and smooth like silk. “She is truly beautiful,” he says repeatedly throughout the day.

Today, Madam Ong, who is now 65, lives in a nursing home. After being diagnosed with diabetes, she experienced a fall which resulted in a stroke that impaired her speech and left her wheelchair bound.

Still, he keeps her within sight – photos of the couple in their younger days line his home and fill his photo albums.

Family disputes have left him estranged from his wife’s side of the family. He is also at odds with his 25 year-old daughter whom he has accused of stealing his money, and often fights with her over her education and career decisions.

“I’m in a difficult position, I have to pay for so many things! Everything that I need for the house, for my own and for my wife are either stolen away by my daughter or spent on bills,” he laments in Chinese.

It doesn’t help that a burglary in the past eradicated most of his family’s savings.

“Sometimes I think of it till I cry, ” he adds.

Nevertheless, Ah Goh trudges on.

On top of selling tissues, he holds a part-time job as a foot masseur on weekends. But due to his age, he finds it difficult to keep up with the physical challenges of the job. He thus needs to continue selling tissue paper to survive.

“What else can I do? No one wants to hire an old man with eyesight problems,” he says, en route to his usual hawking spot.

“There are really good people that buys from me tissues, giving me more and refusing to accept change,” he recounts appreciatively.

Ah Goh is no different. But at the same time, he isn’t just working to survive. After spending some time with him, I discover that he just wants to support his wife so that they can live together again.

On Thursdays, he stops work in the late afternoon, taking a short break before buying her favourite food at the nearby hawker centre. Then, he takes an hour-long bus ride to her nursing home.

When I finally meet Madam Ong, she no longer resembles her husband’s memory.

Bound to a wheelchair, much has changed about her; the once long, black and flowy hair is now short and frayed with age. Her skin, while still fair, has taken on a sickly tint.

The most prominent change, however, lies in Ah Goh’s emotions. Around the woman he does everything for, he talks a lot more, and his laughs are full and deep-bellied.

“You must be better! You must learn how to walk again, our home cannot support the wheelchair,” Ah Goh says encouragingly.

But his words are met with a blank stare.

Due to Ah Goh’s poor eyesight and Madam Ong’s need for special medical attention, much of the couple’s interactions take place within the grounds of the elderly centre. During our visit, I observe as he massages her, and brings her out to the rooftop garden.

With what he can, he tries to look after her.

His wife’s speech impairment and memory loss is a struggle for him to understand. As desperately as he tries to make her feel comfortable, nothing seems to be improving.

And then there’s the stress of making ends meet. The fact that he doesn’t have a good relationship with his daughter only serves to make things worse.

But he loves his wife. She has become his safe harbour, a refuge from his problems.

Soon, Ah Goh will make the trip back to the four walls of his home. But for the next hour at least, his heart is no longer heavy.