One of the questions she received was, “What do you do with so many clothes since you always get so many sponsorships?”

Elaine replied, “To be honest, my closet is exploding to the point where each time I open my cupboard, a mountain of clothes will crash onto the floor.”

In another Instastory later that day, she wrote, “Most of these clothes it’s not cause [sic] I don’t like them but it’s because my cupboard really has not [sic] space and more new clothes are coming in every week ☹…”

The very next day, Elaine began reselling her extra clothes on another Instagram profile of hers, @prelovedbyelaineruimin; over the course of four days, she sold 74 items of clothing to her followers. Just last week, Michelle Tan (@mirchelley) also got rid of her extra clothes by selling “grab bags” of three pieces of clothing for $55 per bag to her 146K followers.

This issue of having too many articles of clothing, whether due to sponsorships or paying out of one’s own pocket, is shared amongst many influencers. I once attended a joint “flea market” where Isabel Tan (@prettyfrowns), Amanda Wong (@beautifuladieu), Melissa Koh (@melissackoh), Christabel Chua (@bellywellyjelly), and several other influencers were selling their clothes.

The influencer marketing industry in Singapore wields an incredible amount of leverage, and currently, this influence is heavily concentrated towards the end goal of encouraging people to buy more and more things, exacerbating the harmful cycle of consumerism and fast fashion.

The harms of fast fashion pertain to two main issues: environmental sustainability and ethical production. Fast fashion runs on a cycle of producing and throwing out at an extremely, well, fast rate; many fast fashion companies, in an attempt to keep costs down and profits high, produce their clothing in poor conditions overseas, where there are often very little protection for the workers producing the clothing at extremely low salaries.

These clothes aren’t meant to last, and they are priced affordably enough for most people to just buy something new when deemed necessary. According to the NEA, in 2017 more than 150,000 tonnes of textile and leather waste was generated in Singapore, and less than 7% of it was recyclable; the waste that was not recycled was incinerated.

When we live in a society where there are new trends constantly popping up, and newer and better products being developed, we buy into the mindset that we need those things. While the shift towards environmental sustainability has already begun in Singapore, one of the main areas that this shift is noticeably absent, and where its presence would be most effective, is in the influencer industry.

According to a 2019 report by Influencer Marketing Hub, out of 800 marketing agencies, brands, and other relevant professionals surveyed, 92% feel that influencer marketing is an effective marketing technique. In addition, 63% of businesses that already do influencer marketing plan to increase their influencer marketing budget this coming year.

Influencer marketing is effective because their lives seem glamorous and desirable, at least in the way that we have been socialised to want. Influencers are always telling us about new products that we should buy, that are fancier and nicer than the ones we already have. We rarely notice influencers wearing the same outfits in multiple posts. They exemplify what it means to be “fashionable”, encouraging others to want to do the same.

In the past, brands might send a few products to big-name celebrities or fashion magazine editors to endorse. Now, everyone—from micro-influencers to Christabel Chuas alike—is receiving these free items that they likely will never wear more than once. This arrangement of sending free clothes to influencers is another way that influencer marketing is complicit in the perpetuation of the fast fashion industry.

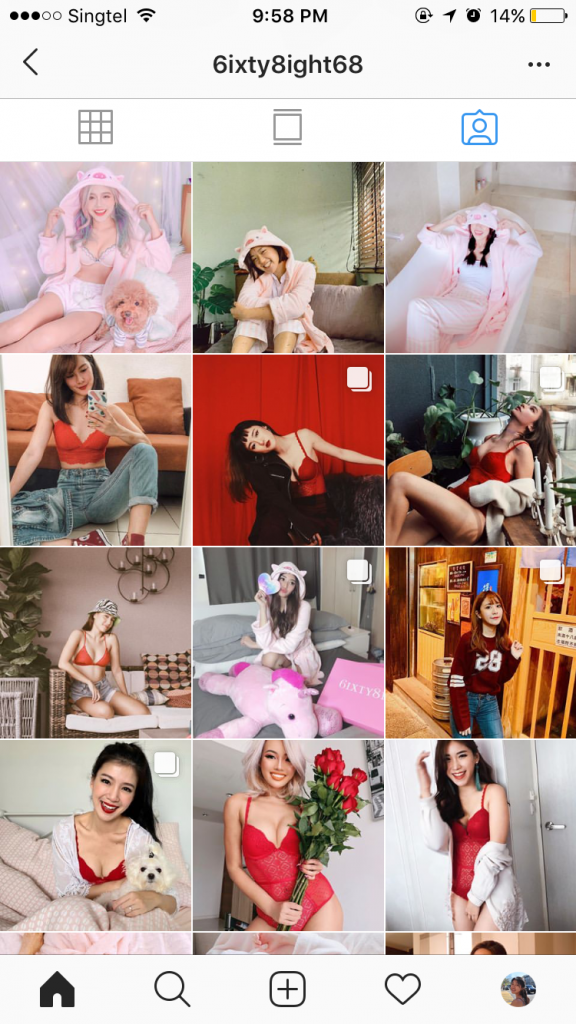

One evening, during the week leading up to Chinese New Year, I was scrolling through one of my Instagram accounts, on which I follow only influencers. Within the first couple minutes of scrolling through my feed, I saw 10 different women advertising for the same lingerie brand, 6ixty8ight (@6IXTY8IGHT68). After some further digging, I realised that the brand had been tagged in over 30 different Singaporean influencers’ Chinese New Year-themed photos, meaning that they had sent free clothing to all of those individuals over that short time period.

This is just a glimpse of how the influencer industry functions in Singapore: the goal is to sell, and to sell only. Everyone involved in the influencer industry—influencers themselves, influencer management companies, brands providing sponsorships, and followers of influencers (including myself)—is complicit in carrying forth the message that the only type of influence important in the realm of social media is that which encourages constant consumption.

If we know and care that this cycle is harmful to the world we live in, and that there are people paying the price for it, how can we do better?

As Tammy Gan and Annika Mock, second-year students at Yale-NUS College and co-founders of the Conscious Living Collective (@consciousliving.co), tell me, “I feel like influencers, just because they are trying to influence a crowd … they have the onus to kind of promote good. And maybe it’s due to ignorance or maybe it’s due to just a lack of care or maybe because they have to earn money … they will teach whoever it is, their audience out there, to not question the kind of things they’re being fed in the media. And they’re complicit in that, and that makes them responsible, and you can hold them to it.”

One way they can do so is to start by being more selective about the sponsorships they choose to take on. Nadra Abu Bakar, who with her sister Ameelia founded @baseable, a local clothing brand that sells eco-friendly basics, shares, “Maybe they should be more aware of what they’re endorsing. Whether or not that means they’re being more sustainable … I’m not sure. But being more, I think, mindful of endorsing certain products might be the way to go.”

In other words, influencers can and should think critically about accepting only sponsorships for things that they themselves would actually need and use regularly, and encouraging their followers to have the same considerations as well.

Influencers can also push back against the fashion culture popular amongst those in the influencer industry, in which every outfit must be the newest and most trendy. They can brainstorm ways to repurpose their clothing, like styling or altering clothes that they already own into different looks, rather than buying or receiving new outfits for events and photoshoots.

Once clothes no longer serve their purpose for the influencer, the next step can be to give new life to unwanted clothes that are still in good condition. One option would be to participate in clothing swaps, either amongst other influencers or even their followers.

This could either be informally and organically, or through existing channels such as Swapaholic (@swapaholicyou); a number of influencers have already participated in Swapaholic, such as Sarah Huang Benjamin (@sarahhuangbenjamin) and Bella Koh (@catslavery). Another, and a more socially conscious, way to pass on clothes would be to donate them to a charitable cause, particularly with stylish clothes that could be worn and appreciated by someone else.

It’s important, though, not to treat clothing donation as a Get Out of Jail Free card, as the enormous quantity of clothes being donated all the time means that much of it doesn’t make it home with someone else, and instead ends up being exported and in a landfill. Thus, donating clothes must happen in conjunction with decreasing our consumption of clothes.

Clothing brands and companies also have an important role to play in this—they can start by evaluating their production processes and identifying the ways that they can shift towards a more sustainable and ethical manufacturing process. baseable’s current model of using bamboo cotton, a more environmentally-friendly material than regular cotton, is already more environmentally sustainable. Nadra’s hope for the next step is to shift away from working with suppliers who tend to have not as good of working conditions for their workers. While it’s not always easy to find sustainable material, good labour conditions, and maintain an affordable product, Nadra explains that she does think it’s possible, and hopes to do so with baseable.

In such a small geographical location such as Singapore, clothing rental companies such as Rentadella (@rentadella) by influencer Ming Bridges (@mingbridges) and Style Theory (@styletheorysg) have already started to facilitate this by allowing people to rent and return clothing for a fee either based on the price of the dress or a monthly subscription. More clothing companies taking on this business model could decrease the need for consumers to constantly buy more.

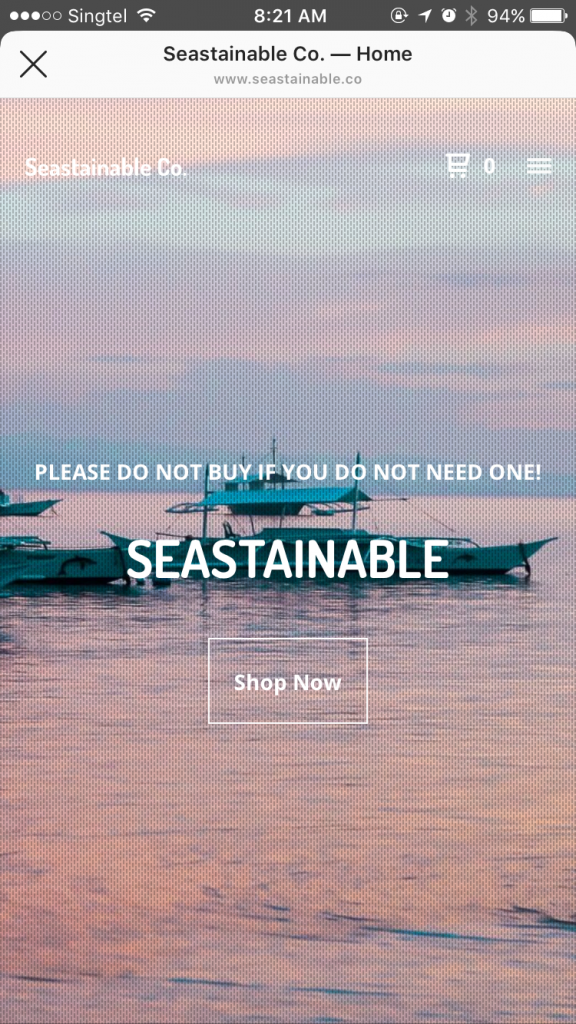

On the big-picture front, companies can encourage their consumers to be critical thinkers about whether they would actually benefit from owning the product or not. For example, Seastainable Co. (@seastainableco) is a business that supports marine conservation by selling metal straws in order to offset plastic straw usage. Although they are in the business of selling metal straws and other sustainable products, their dedication to the cause of environmental sustainability extends to their marketing; on both their Instagram page and their website, they very clearly indicate, “PLEASE DO NOT BUY IF YOU DO NOT NEED ONE!”

This shift could also allow companies to focus less on minimising the cost of production and more on creating high-quality products that people will want to invest money into.

For those of us who don’t have a huge online platform to spread influence on, we can still play a part, starting with reflecting on what kind of life we truly want to live. We have been taught that we should want to always buy, buy, buy (like NSYNC) in order to be happy, but we don’t actually need that. We can and should be more thoughtful about whether we actually need something, and to be more selective about the brands we are supporting with our wallets.

Still, Christmas was coming up and I wanted to get thoughtful gifts for the people around me. I started doing some brainstorming and realised that while I would still be participating in consumerism, I could do so in a way that felt more comfortable and ethical.

My mom, inspired by Ho Ching’s dinosaur pouch, asked me to help her bring home a gift for her friend from The Art Faculty, which sells artwork made by people with autism and other related challenges. I realised that this was the perfect way to find something both meaningful to my friends and family, and supportive of an incredible cause. Even if that meant paying a slightly higher price, it was worth it.

As consumers and people who fall under the influence of influencers, the rest of us also have a role to play. There can and should be a push for the influencer industry to move away from focusing only on material consumerism and instead shift toward other types of influence, such as centering around experiential opportunities, hobbies, or social issues (like environmentalism!). We are the ones who are giving influencers the power to influence us, and we can demand more from the individuals who currently hold the titles of influencers.

We can also uplift the amazing up-and-coming voices that do support sustainable consumption. Some Instagrammers with influence in Singapore that I personally really appreciate include, but are not limited to: @nocarrierpls, @tingkats.sg, @bamboostrawgirl, @wordweed, and of course @consciousliving.co and @baseable.

Admittedly, it’s not easy. I still use way more plastic than I should, and still regularly get tempted when walking past Forever 21.

But if we want to save our planet and to live more conscious lives, we need influencers to care about their impact on the environment and to role model how to interact with fashion sustainably – that is, buy only what you need, use it for as long as you can, and finally give it new life if possible. And we also need to hold ourselves to these same standards.