Everything the Malaysian Twitterati said in The New York Times is true. Over the causeway, the gravy is thicker, the noodles are springier, and the Chendol is sweeter. No thinking person in Singapore or Malaysia will dispute this.

Unfortunately, nobody cares.

Hawker Culture still belongs to Singapore, not because we are better at street food or hawker dishes, but because we have more money than Malaysia. Malaysians may be better at cooking, but Singaporeans are infinitely better at selling/marketing ourselves as better cooks—simply because we have the resources to do so.

Our flavours may be lacking, but most of the world will never know because we certainly don’t lack for money when it comes to PR campaigns, media blitzes, and over-the-top product placement. (Remember that pointless scene in Crazy Rich Asians where Henry Golding lectures everyone about satay? I thought not.)

In short, Singapore owns Hawker Culture because we spend more money (and influence) telling everyone we own hawker culture.

On the corporate/bureaucratic/marketing front, Singapore dominates Malaysia.

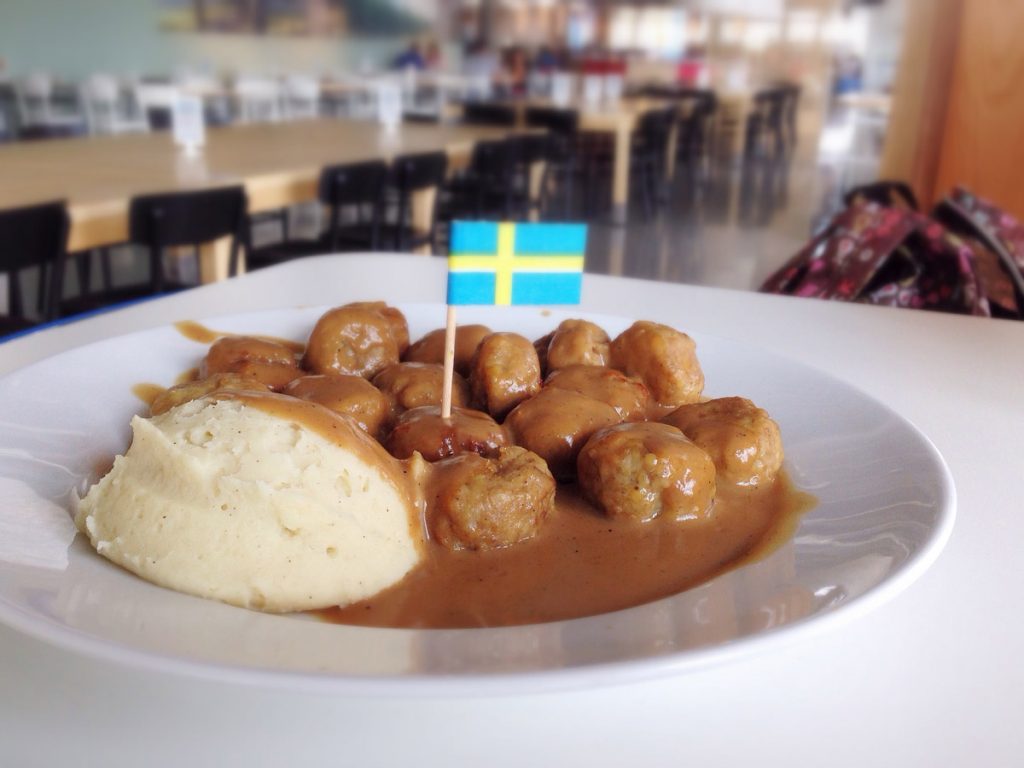

For a textbook example of how this happens, consider the curious case of the Turkish meatball, a.k.a the Ikea Meatball. Earlier in March, Ikea confessed that its famous ‘Swedish meatballs’ were, in fact, Turkish in origin. They were brought to Sweden by King Charles XII, who ‘discovered’ them during his exile in Anatolia.

This confession, however woke, will not change the identity of the meatball one bit. Ikea is a modern Swedish empire, and it sells billions of meatballs under tiny yellow-and-blue Sweden flags. The furniture names are in unpronounceable Swedish, and the stores’ colour scheme is literally the national flag.

Under such circumstances, Sweden owns the Turkish meatball, as surely as Americans own Hamburg’s hamburger. You could argue for days about the cultural appropriation, but it doesn’t change the fact that we think, dream, and write of the meatball as ‘a Swedish product’. Until such time comes when Turkey forms its own global furniture empire or match Sweden in ‘soft power’, Sweden effectively owns its balls.

Sichuan has been eating Mala long before the rise of modern China, but I would argue that Mala’s popularity owes everything to China’s rise in the 21st century. In the 1980s, Mala was appreciated by a small Chinese elite who could afford to travel to the economic rustbelt/unspoiled paradise that was Sichuan Province.

However, with the rise of China and the growing economic power of Sichuan, Mala was able to travel far beyond the confines of its birthplace. This is not because Mala had magical properties or was uniquely tasty. It happened simply because newly-wealthy Chinese entrepreneurs had the capital to expand, expand, and expand, spreading the Mala flavours far and wide, until everyone was both familiar and fond of it.

It colonised the rest of China in the early 2000s, and now, thanks to Hai Di Lao, You Ma You La & other Chinese corporations/franchises, it’s coming to a hawker centre near you.

That’s why Malaysia is always on the defense when it comes to food. Not because Malaysia’s food is inferior, but because Malaysia is less aggressive and less well-connected than Singapore.

Think about Tiger Beer’s sponsorship of street food events in New York. Think of Bourdain Market’s ‘Singapore-style’ hawker food hall and Gordon Ramsay’s Singtel-sponsored hawker challenge. Think about our hawkers’ hard-won Michelin stars and how it was mysteriously ‘supported’ by STB.

In short, the chequebook is mightier than the wok. We often attach sentimental values to food with words like ‘love’ and phrases like ‘live to eat’, but it’s important to remember that the history of food is intricately connected to the history of capital, power, and empire.

The question of culinary superiority is not just a matter of flavour and texture, but also a battlefield where economy, foreign policy, and government intersect. Just look at Europe’s hegemony over what constitutes good food, or America’s unhealthy influence on our diets.

Ipoh or KL might have great bak kut teh and a lively ‘scene’, but it won’t matter because Malaysia’s government is poorer and less organised than S’pore’s. Until that changes, Singapore’s ‘hawker culture’ will reign supreme in Brussels, London, and New York, even if Malaysian food owns Singapore.

So Malaysia, please don’t hate the player, hate the game.