Here we go.

SMRT. (General.)

GST Voucher. (Elections.)

Pokémon Go. (Passé.)

Unless you’re an active player of Pokémon Go, chances are, your response to the last prompt would have resembled mine.

As a game, Pokémon Go is unusual in the vitriol it attracts. Certainly, no other online social game, such as Fornite or DOTA, has been a magnet for comments like these (note: not limited to Reddit) made by people who aren’t invested in the game:

But barely a few months later, the excitement soured. The original player base of teenagers and young adults who grew up with Pokémon abandoned the game en masse; Pokémon Go was seen as a walking and swiping simulator that did nothing to capture the magic of the original GameBoy games. Instead, it became and still is associated with “old uncles and aunties on e-scooters”.

Why, then, are we publishing a story about a languishing viral trend that seems to have lost any cultural significance whatsoever?

Because Pokémon Go might be the panacea to a myriad of social problems we are facing today. Sort of.

“Relax. You’ll enjoy it,” he purrs into my ear.

As the appointed time arrives, I’m surprised to spot a modest number of people gathering. Clearly, I was wrong to think the trend had died; from the shy, shifty looks exchanged, it’s obvious that everyone is here for the same reason.

The participants join their groups, and as the timer reaches zero, a huge Latias appears on Zach’s phone (for the uninitiated, it looks like a stylish flamingo water-float come to life). He starts tapping furiously at his screen—his summoned Pokémon, in response to his commands, starts dancing sexily and shooting substances at Latias.

Less than three minutes later, it’s over.

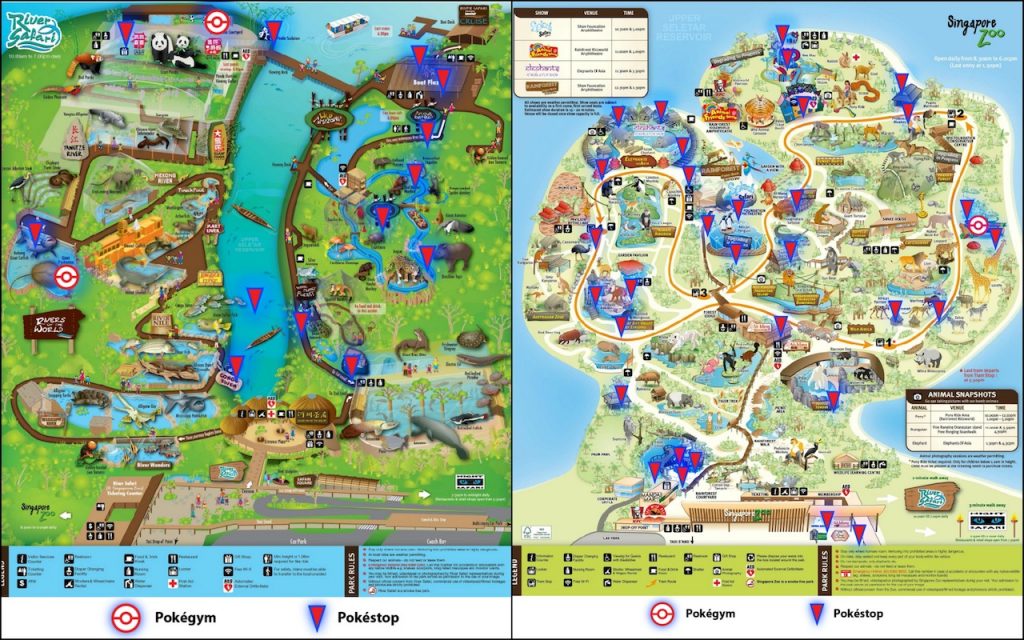

I had witnessed my first Pokémon Go raid: a timed, location-based event in which people collaborate in taking down a legendary Pokémon for the chance of catching it.

The raid did nothing to change my mind.

However, it revealed to me a dimension of the game I was hitherto unaware of. Beneath the frantic finger flicks, there was a camaraderie amongst the players. It had an almost rebellious character to it, like that of the outcast who knows he’s engaging in a countercultural activity.

Indeed, this is precisely the aspect of Pokémon Go that I wanted to find out more about from Zach. Why is he still playing Pokémon Go, and who does he even play it with? How have the two years of playing it changed the way he goes about his daily life?

These social gatherings cemented Zach’s commitment to the game.

“A lot of people were playing. So it felt like there was a very big player base. It was exciting and it was the hip thing to do.”

He adds that it was hence a good thing when there were “a lot more community features [introduced to the game], like raiding and trading,” and that made it “a lot more fun to play with other people”.

In other words, while the AR aspect of the game was the sexy black dress that ignited the start of Zach’s relationship with Pokémon, the social aspect of the game was the ring that sealed the deal.

“We also do other stuff like during Christmas we had a Christmas dinner; we just had a Chinese New Year steamboat,” he tells me.

There is a pseudo-kampung spirit, a social glue that Pokémon Go has slathered onto this particular Jurong East community of trainers.

“[When] we see each other at Sheng Siong or at the park we’ll just say hi, that kind of small thing.”

In other words, thanks to Pokémon Go, people are walking more (to hatch their eggs) instead of taking private transport. Zach, for instance, would “exercise with Pokémon” and would “even run with it”.

There are even tales of health benefits brought about by Pokémon Go:

Zach himself often catches and trades Pokémon with his mum, especially when he goes overseas and smuggles back flocks of regional Pokémon that are not available in Singapore. Indeed, for many, trading Pokémon with their parents takes on an almost symbolic value of filial piety:

“I usually wouldn’t speak to older people cause I’m shy,” he says, but, because a large proportion of Pokémon trainers in his Jurong East group are older than him, he now fraternises with people of all ages.

Even so, Zach is quick to raise a caveat: Pokémon Go is “not this miraculous bonding thing where people who see each other play will automatically hit it off and speak to each other.”

“Sometimes, we raid quietly [and go home].”

Zach shares a few other anecdotes of him interacting with strangers, but this is my favourite:

“Once I was on my way to a raid and there was a group of makciks who were like ‘eh boy you also play Pokémon ah?’ So they stopped me and they kept showing me their Pokémon. And they were like ‘show us yours leh show us yours leh.’”

He pauses, turning his phrasing over in his head.

“I showed them my Pokémon,” he finally clarifies.

Then he goes on, “I never met them again but I remembered the incident.”

Hearing about Zach’s friendship forged with his fellow trainers, I grew slightly envious. I’m at that age when it’s hard to make new friends or keep in contact with your old ones. People are disappearing into their world of BTOs and carefully plotting their path in the corporate world. So it strikes me as something rare and special for a group of people to bond over and engage in an activity that is fun for its own sake, and not because it confers status, fame, or money.

Zach’s anecdotes have showed me how Pokémon Go has in fact become kind of community glue. And its intrinsic appeal can be harnessed to solve a number of social problems that our various ministries are already hard at work tackling.

Need to combat diabetes by encouraging people to walk 10,000 steps a day? We don’t need the National Steps Challenge, we just need Pokémon Go.

Encouraging intergenerational interaction within families? Proximity Housing Grant and 3Gen flats are great, but also: Pokémon Go.

Recapturing the kampung spirit of yore? Residents’ Committee events usually have an entry fee—Pokémon Go is free!

While I am clearly being farcical—as Zach points out, Pokémon Go isn’t some miraculous bonding tool that will solve all ailments—there is nevertheless clearly something compelling and effective in the game’s ability to mobilise and solidify communities.

So perhaps we should take a leaf from its book and stop throwing cash at every problem. As Pokémon Go proves, communities and social interaction spontaneously spring up when people share a narrative.

In the case of Pokémon Go, the narrative is that they are all trainers, seeking to catch ‘em all; in so doing, everyone becomes an equal in the world of Pokémon Go, thus linking individual lives together.

As Zach concludes, “The main point [that Pokémon Go has taught me] is to abandon your stereotypes [and not make] any assumptions [about people].”

For him, Pokémon Go is the great leveller.

(Yes, pun intended.)