Two months ago, yours truly, a millennial who possessed the sum total of zero knowledge on art appreciation, was tasked with writing about an art exhibition.

This was the showcase for the President’s Young Talents 2018 at the Singapore Art Museum, and for fear of getting lost in artistic mumbo jumbo, I instead approached gallery sitters for a more relatable take on understanding the installations. Consequently, they opened my eyes to new and interesting interpretations of art.

Two months later, the winners were announced. Weixin Quek Chong won the grand prize with her artwork titled sft crsh ctrl, while Yanyun Chen‘s The scars that write us garnered the most votes by members of the public at the exhibition, clinching the People‘s Choice Award.

Even then, I hardly knew anything about the creators of these pieces of work.

What is it like being an artist in Singapore? Do accolades matter when your work isn’t easily quantifiable? And perhaps more importantly, has life changed for the pair after winning?

I was hungry for more.

What she can say with certainty though, is that she stuck with the art elective programme back in secondary school as it was the only subject which left her alone to do whatever she wanted. Grades didn’t matter, and Yanyun thrived in the freedom the subject offered.

“I didn’t have to perform for it—in the precise sense of staging a performance for a very narrow notion of excellence—and that was as much freedom as a student in Singapore could ask for. I guess this is just a very prolonged teenage rebellion that is still in progress!” she says candidly.

Her pursuit of freedom, both in thought and craft, coupled with a playful rebellion against the stringencies of Singapore’s unforgiving education system, meant that Yanyun had no endgame in mind.

“It’s been a privilege to be able to embark on a series of adventures, and encountering stories that needed to be told. Where this necessity stems from, I find difficult to say. I simply followed my nose when it came to interesting skills to learn, questions to think about, puzzles to solve, stories to tell, and a craft to hone and polish.”

It’s a remarkably simple work ethos which has obviously paid dividends. But as I soon find out, accolades aren’t something she concerns herself with.

Of course, this doesn’t mean recognition counts for nothing.

Yanyun is greatly humbled by the tremendous acknowledgement The scars that write us has received, and remains extremely grateful to the curators of the arts scene for giving her the freedom and opportunity to include classical drawing techniques in her installation—something rarely seen in contemporary art. Being a self-confessed introvert, she’s also thankful to the many strangers who shared their personal stories with her.

While doing justice to their stories was paramount, she originally had no idea what the “end point” of her installation was. As her profession doesn’t have clear KPIs or standards to meet, Yanyun never really felt that her installation was complete.

Until her cousins visited the museum.

“During one of the museum tours, they actually cried when they saw my work. They had contributed their scars and stories to the installation and although I didn’t know how exactly to react when that happened, I had an overwhelming feeling that the work had served a purpose and was done.

“It was a reminder of what visual art and story craft were able to do and I cherish that feeling.”

Even then, Yanyun isn’t yet sure how significant the win will be for her artistic career. Her journey thus far has been a meandering one encompassing animation, philosophy, and contemporary art practice (to name a few) with no linear trajectory per se.

“The word ‘career’ implies a form of a line or direction, but as far as I can tell, my compass seems to be a bit crooked,” she says.

That said, this being the planet earth, there are the realities of being an artist in Singapore. And Yanyun is well aware of them. Like any other working adult, Yanyun has bills and tuition fees to pay off as well as a family to look after. The key difference is that an artist’s work is, by nature, experimental.

“The expenses for every project are very different and each one requires time, patience, and space to try, err, and fail. There is never enough time.”

It’s a Herculean juggling act, and in an ever-changing world that seems hell-bent on stifling artists in a myriad of different ways (censorship, classification, limited funding, institutional taste-makers / gatekeepers etc), Yanyun keeps her definition of success simple.

All she wants is to continue being able to tell stories through her work, without having to worry about the practicalities of living or the limits of space.

“It is undoubtedly a tall order to ask for freedom, opportunity and time. But hopefully, in time, with time.”

Weixin shares that as a child, she would often lose herself in books and visuals, making it difficult for her to separate reality from fantasy. With a liberal arts-based home education, she was always either drawing or making things, later focusing on literature and music as she got older.

Thanks to the constant encouragement of her creative interests from her graphic designer aunt, Weixin then decided to apply for a course in visual studies offered by LASALLE, and received her bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts, followed by her Masters in Fine Arts from the Royal College of Art in London.

There is no doubt that Weixin is highly accomplished in her field. Like Yanyun, she too never had materialistic goals when she first got involved with the arts. Instead, it was about self-fulfilment, and her only aim was to create things that both pleased and interested her the way books and music could.

“Creative expression has always been my main method of alleviating and coming to terms with how strange it is to exist as a human entity. It’s my way of making and searching for space—even if it’s temporal—to be in,” she tells me.

Realising how much untapped potential there was in these creative communities, she embarked on small-scale collaborative projects and exchanges to see what they could lead to while also doing her part to foster an even stronger sense of community. It’s since become her long-term goal and Weixin is always looking for ways to contribute to the creative scene.

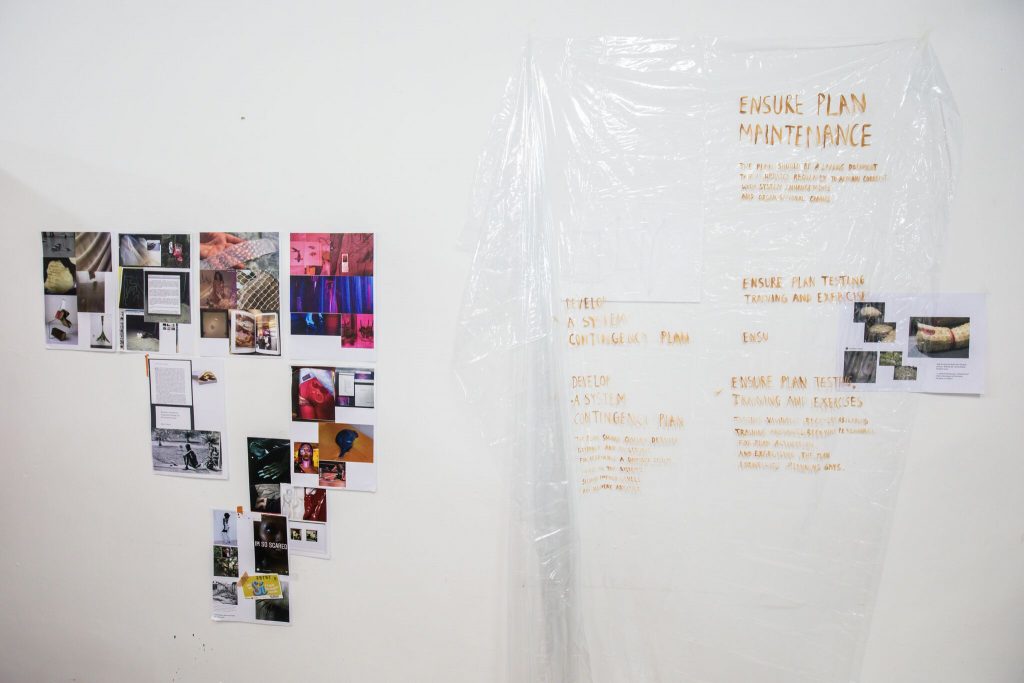

According to Weixin, making sft crsh ctrl was already the most significant turning point in her artistic career, and winning was an unexpected bonus. She had joined the competition simply to test herself in terms of planning and executing a project of such a large scale. With the support of the Singapore Art Museum, she managed to bring one of the many ideas she’s amassed over the years to life.

Describing the win as “encouraging and rejuvenating”, Weixin tells me that it’s truly heartening to know others value her work and recognise the effort that goes into the art of creation. Yet, if such commendations don’t come, artists must still continue doing what they do.

“Yes, accolades can provide a huge boost psychologically, financially, and societally, but I don’t think winning them should be something an artist should center their practice on. Worrying about how to achieve more external validation according to current (and changing) terms is a massive self-imposed restriction.”

Her definition of true success is instead to be an artist whose work brings something meaningful into the consideration of communities, without compromising the integrity of projects which might not be appropriate or relevant to the times.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Echoing Yanyun’s views on the hardships faced by artists, Weixin opines that for majority of artists in Singapore, going into art full-time is extremely difficult, and a second job is often required for survival.

As happy as I am for both Yanyun and Weixin, I’m hesitant to say that their wins will likely redefine their careers. It’s great that both women were given the credit they were due, but until Singaporean attitudes towards the arts changes, they will remain criminally undervalued by society.

To recycle a point made in my earlier article, contemporary art is often open-ended in nature, and unfortunately, easily dismissed by anyone who fails to understand its meaning. We might not realise it, but this dismissal also extends to the artists themselves.

The creative process isn’t something many are privy to. As a result, we tend to underestimate the sheer amount of work that goes into creating even the simplest piece of art.

Which is honestly a damn shame because art isn’t just about who can amass the most number of accolades, or who manages to sell the most paintings. Artists aren’t about winning but rather, expressing themselves while trying to broaden their audience’s perspective.

And in my book, this deserves all the respect in the world.