“I’m not asking if you would sleep with Song Joong-ki,” I explain for the third time. “I’m asking if you want him to throw you over the kitchen counter and do nasty things to you!”

“Well,” Phoebe, a friend of mine pauses before saying, “It’s more of a … I want him to hold my hand, stroke my hair and take me out for ice cream kinda thing. Oh god I’m such a mindless consumer of K-dramas!”

“Heh, so no rough sex?” I ask again.

“Mm, nah. I would totally have his babies though,” she adds.

“But that’s not exactly the same thing is it?” I think to myself.

We’re talking about Descendants of the Sun and Korean idols because I’m curious about whether Asian masculinity can be defined, and whether Korean pop culture has influenced this discussion in any way. After all, Korean idols are heavily marketed on their chiseled, boyish features, along with their often impeccable fashion sense.

Female fans like that they aren’t atypical stereotypes of masculinity, and present a dreamy alternative to the sloppy, frat-boy types that Hollywood films thrive on.

Yet the toxic masculinity that lives in my culturally conditioned bones can’t help but wonder: It’s one thing to imagine Korean idols as ideal romantic partners, and another to imagine them as hook-up material—the sort that drips Ryan Gosling type sexual energy that makes you imagine yourself in a 50 Shades of Grey scenario with.

Earlier in our conversation, Phoebe had helpfully pointed out that most women tend to categorise men as “will date” and “will fuck.” So then, I thought, are Korean men not fuckable because they look like girls? Does that then mean that no one sees Asian men as inherently fuckable?

Why, as an Asian man, am I bothered by this notion?

Eventually, I quizzed her again, “So if rough sex … who?”

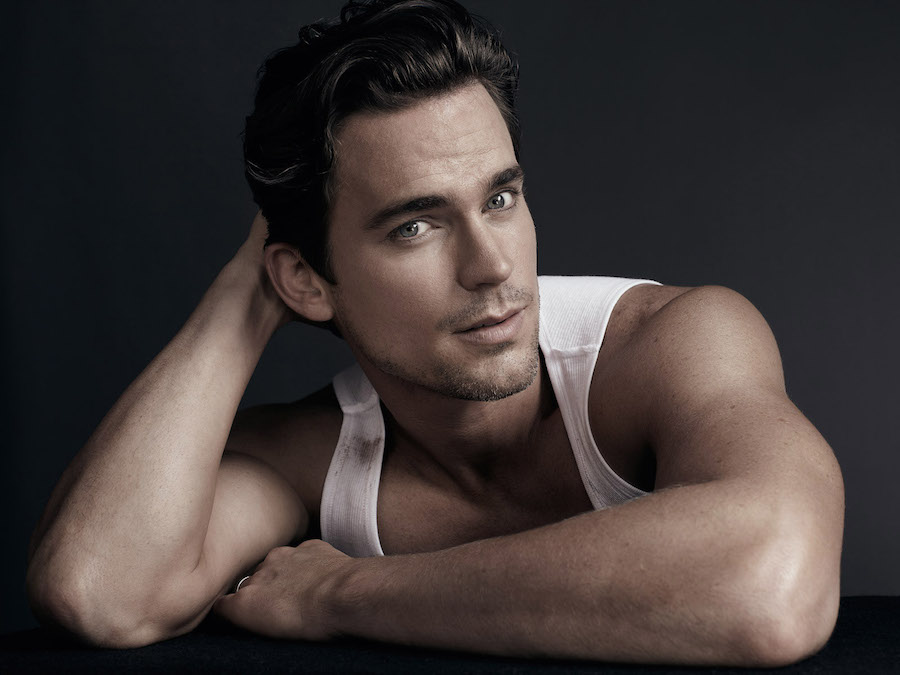

She literally laughs out loud before looking down and almost whispering, “Um, Channing Tatum?”

To me, explanations revolving around how Western celebrities are more attractive because of our post-colonial hang-ups or because White people are culturally more outspoken and spontaneous have always felt like overly simplistic explanations.

In Boys Over Flowers, the quintessential Korean drama, most of the male characters are chock full of contradictions. They are portrayed as having either distasteful or inaccessible personalities, but also as having the potential to be better people. As the series progresses, they reveal their vulnerabilities. They embody the promise of sensitive men just yearning to blossom beyond their hard and rough exteriors.

They play characters who need saving, who will charm, commit and comply so long as you keep trying.

“For sure, this has its appeal. But you know what, they’re not sexy.”

This is Andrea, another Korean pop culture obsessed friend I’ve enlisted to help explain whatever it is I’m trying to explain. I then tell her to name one Asian actor she finds sexy.

Not even blinking, she says, “Tony Leung, duh. Throw in some Edison Chen too while you’re at it, thanks!”

“Is it because they don’t look like girls?” I ask.

“Yeah and also, you know, there’s that whole vibe and that look they always have in their eyes. I can’t really explain it, it’s part mysterious presence part suave, bad boy persona.”

At this point, it becomes clear to me that Asian masculinity, if there even is such a thing, is a complicated and perhaps, even non-existent thing. Western audiences are influenced by what they have access to—Hollywood’s active perpetuation of Asian stereotypes, from Mr. Yunioshi of Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Ken Jeong in The Hangover.

For the cosmopolitan, female Asian audience, it’s less simple. They consume both Western and Asian media, yet they still come out of this with different ideas of what Asian and Caucasian bodies represent.

At the end of our chat, Andrea tells me, “Just because I like staring at Godfrey Gao doesn’t mean I will only date men who look like him.”

She goes on to explain that in life, whether we’re looking at White or Asian celebrities, there will always be men like Godfrey Gao and Daniel Henney, and men like G-Dragon or Lee Min Ho. Between the buff and the beautiful, everyone has a preference, and not everyone’s preferences actually affect the way they date.

“Look at guys like Jake Gyllenhaal, Joseph Gordon-Levitt or Ed Sheeran, these guys are basically the Korean idols of American pop culture,” she concludes.

And she’s right. Later, I realise how dismissive it is to think that the appeal of Korean idols stops at their pretty boy facades.

In Korean dramas, every male character stands a chance. From the cocky playboys to the quiet types, the sexual tension is equally distributed. This is unlike Western depictions where the nerds are inevitably friend zoned. When you watch a Hollywood film, you know who’s going to finish last.

Sure, some see Korean idols and the men who emulate them as the better dressed and more sensitive alternative to gruff, hyper-sexual and self-interested Brad Pitt types. But for girls like Phoebe and Andrea, the main attraction of Korean idols and the dramas they act in lies in how the audience is never sold one rigid idea of romantic viability. They like the idea that all men get their turn.

Eventually, I acknowledge that the need to explain Asian masculinity is, in its own way, an incredibly “masculine” impulse. It’s a misguided and egoistic endeavour, in the sense that all I’m really trying to do is resist what I’ve perceived as the media’s emasculation of Asian men.

Still, I can’t help but feel some resentment at the idea that while Korean idols have made on-screen romance more democratic, women still don’t see these men as sex objects. These flower boys are still ‘will date’ material, not ‘will fuck’ objects. And this irritates me.

While I’m aware that this is a clear by-product of how I perceive Asian masculinity, it’s still a little deflating to think that we are less sexualised than Western men. In the meantime, I guess I’ll just have to work at making up for this with a badass personality.