All photography by Viola Gaskell.

At the end of Temple Street, near the famed Tin Hau Temple, the sound of blaring speakers and heartfelt bellows fill the humid night air. At 7pm, Hong Kongers set up their tents, tables, chairs, speakers, and TV’s on the broad sidewalk. Karaoke machines are switched on, Gaohus tuned, beers iced, and the nightly ritual begins.

“I am here every night, rain or shine,” says 62-year-old Benny Chan, the owner of the tent closest to Temple Street Night Market. His is just one of the many Karaoke plots here on this stretch that has come to be known as Karaoke row.

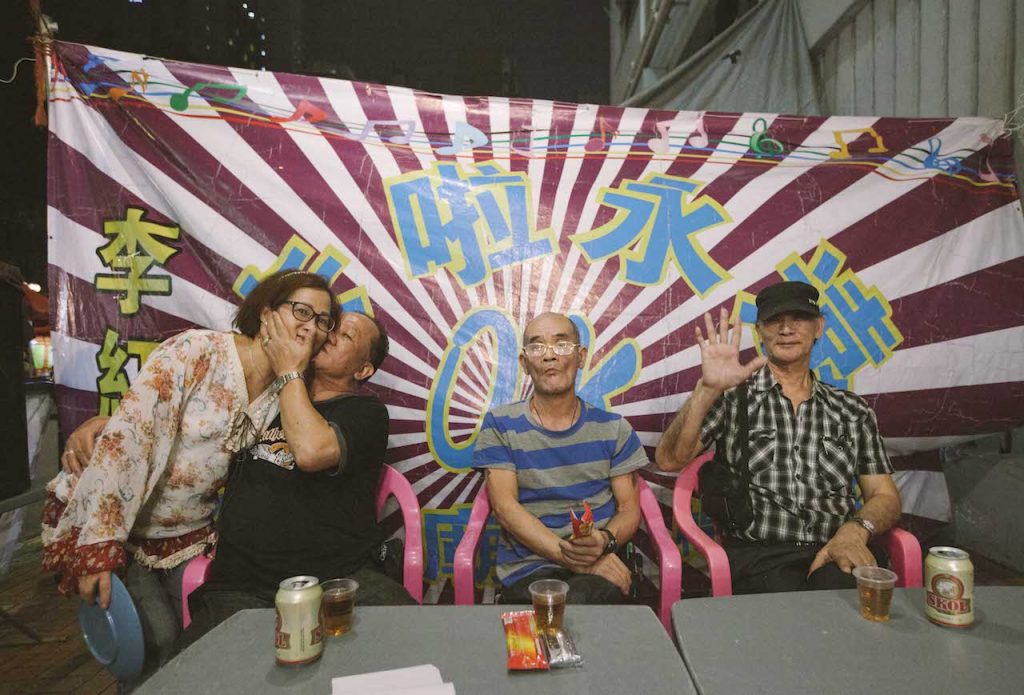

As four regulars assemble hot pink plastic chairs around a pair of mismatched tables, the most extroverted of the bunch, a heavy-set man in a black “Southern Cycle” T-shirt, tells me he started coming here when his wife left him. “Same with these guys,” he says, waving a hand at the others. One of them, with forearms covered in temporary tattoos, has clearly been drinking already, the others get started on their Tsing Taos right away.

“Our wives left us, we have nothing to go home to, so we come here,” he says, “Life can be hard or it can be easy. When my wife left I decided to make it easy; I came here and sang the song I Really Miss You, and I started to move on.”

The older man in round-rimmed glasses to his left smiles and nods his head as if in agreement; the two have been friends for 40 years. They met the others here and tell me: “It’s very simple making friends here. You just say, ‘Hey come have a drink,’ and then you’ll probably be friends.”

The tents have been here since the late 80’s, and each one has its own unique style. Benny hires a keyboard player to accompany the singers while his neighbor strictly uses a VCD player. The oldest stall, round the corner from the rest, resembles the beginnings of Karaoke row, when it was made up of live musicians accompanying Cantonese opera.

At this opera tent, a musician plays the Gaohu, the most classical stringed instrument in Chinese Opera. The accompanying percussionist plays an instrument nicknamed the “tuk tuk chang chang” for the sound it makes. Four old timers camped against the nearest concrete wall listen with their eyes partly closed as if allowing the music to take them back in time. The owner says this has been a Cantonese Opera tent for 40 some odd years now. The original owner handed the reins to her before he passed away.

Seventy-year-old Mary Lee is somewhat of a star on Karaoke row. In her thirty years of performing here, she has developed a following of sorts. With her understated makeup and bejeweled black sneakers, Mary commands the attention of both the tent and passersby alike. When a young tourist stops to video her performance from across the street, Mary, with her polished vocals and effortless stage presence, is unfazed.

Vibrant Chinese characters spelling Mary’s name cover the well-lit vinyl signs in her tent. Eva seems to run the logistics, but Mary is clearly the Maitre d’, and the star. “I am here every night,” she says, “Except during typhoons. This tent gives me satisfaction, it gives me a stage. More importantly, it helps people in poverty enjoy themselves. They pay 40 dollars and they get to have some fun for the night. That isn’t very common in Hong Kong.”

Some nights, caretakers bring the elderly to Karaoke row for a dose of entertainment. At Christmas time, a nearby church brings disabled adults to Mary’s tent and the front row is turned into parking for wheelchairs. Eva has added a handful of Christmas songs to their catalog so they can carol to VCD.

Mary thinks that people are drawn to the freedom of Karaoke. It is an opportunity to indulge in unhurried self-expression in a fast-paced, densely packed megacity. As people sing they release emotions that might otherwise be kept below the surface.

“During this experience, people bond with the place,” she says, “They’ve worked through something here, so then they come back over and over.”

Occasionally, tourists spill over from the night market and perform an English song for 20hkd or for free if preceded by a decent sized beer purchase. But the tents are sustained, for the most part, by regulars. Ena Chan, who has been coming for 21 years, says the tent she helps run has a handful of regulars every night who spend 200 to 400hkd. “I know that some of them started coming because they were lonely or stressed, then they made friends. You get to know people easily here,” she adds.

With the growing popularity of personal microphones developed just over the border in Shenzhen and easy to use song apps, Karaoke is an increasingly individualistic act among Asia’s youngest generation. Aspiring young vocalists use the machines in videos they post on Youtube and WeChat, garnering attention while bypassing the nervousness that come with a stage and live audience.

Here on Karaoke row, the impetus belongs to the old world of Karaoke: an antidote to the loneliness and boredom of returning to a cramped, empty home. While the origins of Karaoke row are ambiguous, one of its oldest clients tells me that it started when many Japanese immigrants first came to Kowloon. They didn’t have a community here and weren’t generally accepted into the Chinese communities, so they formed one here at the end of Temple Street, close to where many immigrants lived.

Benny, who has been running his tent for 14 years, says he thinks of Karaoke row as a refuge for people who work hard all day and need to unwind at night. His operation is a labor of love, and with the electric bill and rental of a storage stall nearby for his tables, chairs, and other things, he essentially breaks even. He and his business partner also pay their keyboardist 300hkd a night, which he says, preserves some tangibility.

Six years ago, and eight years into owning his tent, Benny discovered that he had stage three colon cancer. He pulls up his shirt to show me a four inch scar on his abdomen.

“This place gave me motivation to keep fighting. Some of the friends I’ve made here came to visit me in the hospital, they were definitely part of my support group,” Benny tells me.

When I ask him if he’ll retire any time soon, he responds, “I’ll retire when I cannot move”.

When Benny takes his turn with the microphone he begins a duet by the classic Hong Kong band Beyond—one of his favorites. It is a perfect fit because his voice has a classic quality, like it could fill any room with just the notion of a sweet past. Beyond is one of those tried and true bands that seem to epitomize Hong Kong identity, but around here the fandom is even more local. Benny says he earned his followers by teaching them to sing. One of his proteges is up next.

At 11pm, the police come and tell the owners to close up. The music is astoundingly loud, and the tents seem to be competing for decibel space.

“Blame it on our worn out ears,” says one of Benny’s regulars, “I think we’d stay later if they let us, but the police say it’s too loud, so we go home.”

After a brief pause, he adds: “Reluctantly.”