Like most twenty-nine-year-olds, Mr Danial works 8 hours a day, 5 days a week.

During that time, dressed in a black polo tee and pants, he stands largely motionless in a quiet room, keeping an attentive watch over the area he’s been entrusted with. His job description includes interacting with people, but unfortunately, it’s something he doesn’t get to do very often. If at all.

As much as it might sound like it, Mr Danial is not a security guard.

Instead, he’s one of Singapore Art Museum’s gallery sitters—a profession that’s grossly underappreciated and often overlooked.

Preferring to keep to myself whenever I visit a museum, I must confess that I’ve never paid them any attention. In fact, I didn’t even know such a job existed. At least not until I found myself struggling to understand the five artists of the President’s Young Talents 2018.

Desperate for any grain of clarity, I turn to Mr Danial for a little help interpreting the artwork. After all, gallery sitters spend so much time around the art, surely they must have insightful perspectives, right?

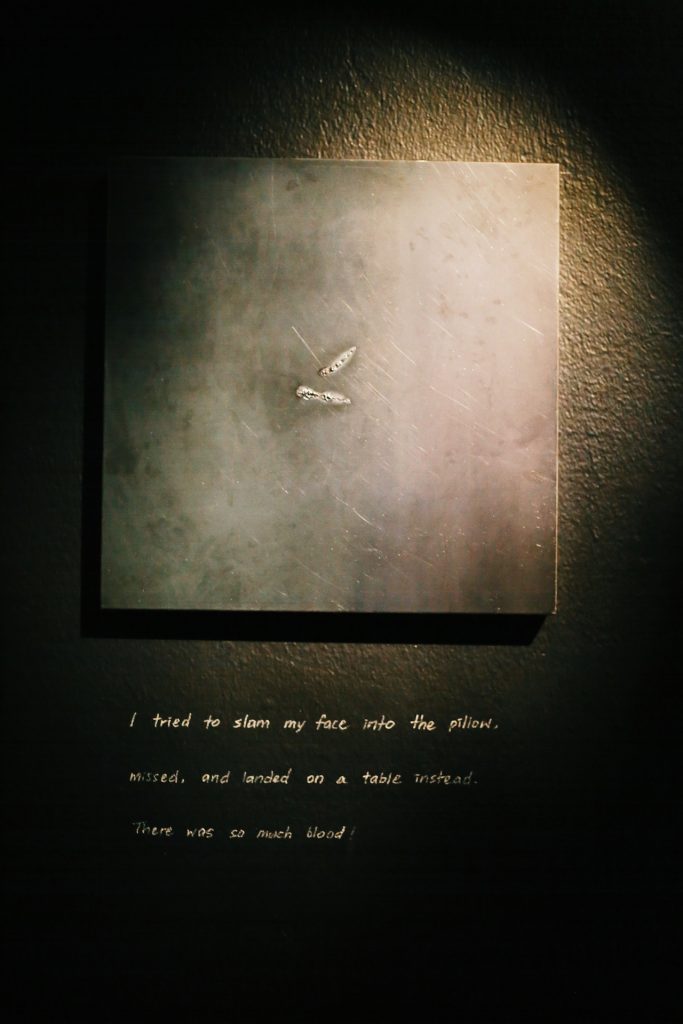

Appearing like welds on a metal backboard, the artist makes the scars the centre of attention, contrasting the usual practice of hiding them under clothing. Together with the accompanying stories on how the scars were obtained, the installations make for a hauntingly beautiful spectacle.

“In this room, the artist talks about keloids but they are just one kind of scar on your body. Take me for example, even though I don’t have any keloids, I have a lot of scars. And scars aren’t just about physical marks. They can be emotional or mental ones as well. Something only the owner will know about.”

Urging him to tell me more, Mr Danial then offers to show me his favourite part of the room.

Following him down the dimly-lit walkway, we soon arrive in front of the artwork in question. What appears to be a fairly normal story about an accident is viewed very differently by him.

“This artwork really spoke to me because I used to have that mentality.”

Almost as soon as he shares his interpretation of the artwork, I find myself filled with an overwhelming sense of sadness on his behalf. I mean, to equate concrete to a pillow?

Perhaps reading the sudden shift in my mood, Mr Danial quickly adds that he’s in a much better place now and has, in part, the gallery to thank.

“Being in this darkened space for such a long time really makes you think and your mindset can totally change,” he tells me, before elaborating that the room is like a reflection of his old self.

Even though he appeared bright and happy in front of his friends and family, he used to keep himself in his own dark place. Over time though, he’s come to realise that while scars may not always heal properly, at the end of the day, life goes on.

And that’s exactly what I do.

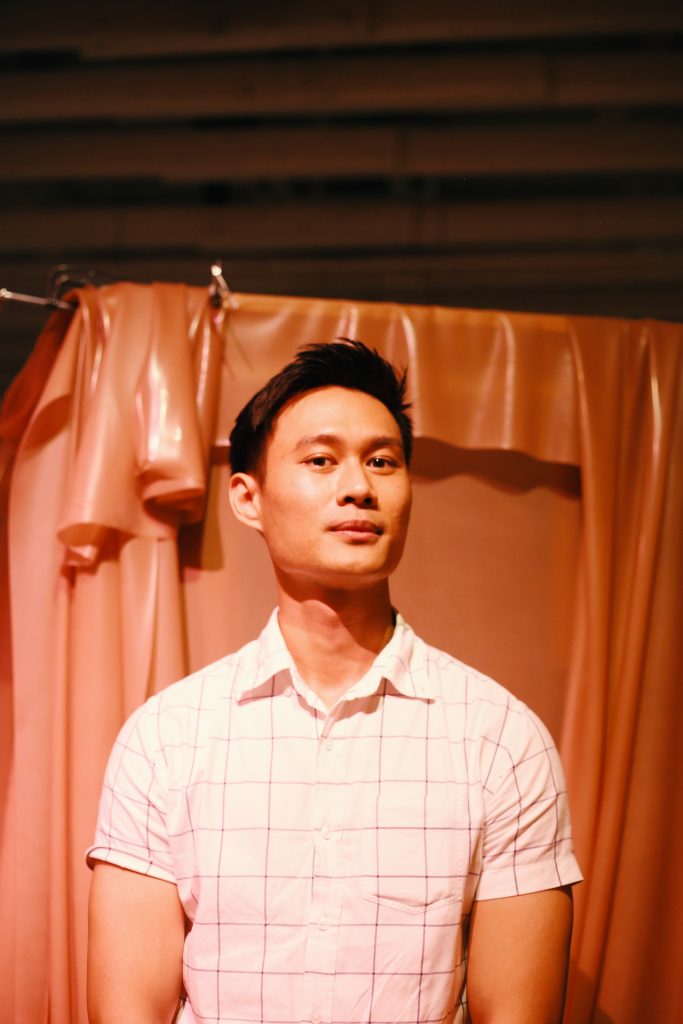

Astounded by what else I might’ve been missing, I approach Mr Faris Nakamura, the visitor services executive of Singapore Art Museum. We’re standing in the middle of Weixin Quek Chong’s installation titled “sft crsh ctrl”, and in all honesty, I have no idea what I’m supposed to think.

The entire gallery is bathed in shades of warm pastel colours. Overhead, the sounds of water flowing and the soft crinkle of plastic play from one of the speakers in a constant loop. Wooden frames draped with sheets of latex make up most of the room’s décor, accompanied by banners depicting chain links made of rope. Elsewhere, there’s also an installation made up of furry, fox-tail anal plugs.

Everything makes for an extremely peculiar sight but Mr Nakamura – who’s a contemporary artist himself – tells me that my bewilderment is not altogether unexpected.

Explaining that the installations are meant to challenge visitors’ understanding and expectation of materials, Mr Nakamura shares his initial experience with this gallery.

He goes on, “If you really break it down however, I think that’s her concept. It seems like the artist wants you to take these elements and textures which are presented in non-traditional ways, and create your own narrative. I thought that was very interesting. After spending a bit of time in the space, I had words such as beautiful, feminine and sensual to describe it.”

To him, the space we’re in is a blank canvas and embodies how contemporary art can be anything and everything. Unlike paintings or sculptures reminiscent of the Classical period (in which people focused more on aesthetics), what’s unique about this gallery is that based on a cursory viewing, you wouldn’t know what the exhibition is about. Instead, the elements of story-telling and the sharing of experiences come into play.

Mr Nakamura gestures to one of the installations, in which light seeps through a thin piece of cloth draped over a frame, before elaborating.

You want to hear from the artist and if they’re not around, you discuss the piece with your friends. Someone might say it reminds them of Wayang Kulit or it might trigger a conversation of the time a friend saw your shadow as you changed behind some blinds.

There’s definitely no right and wrong in art. It’s about the interpretations and the interactions that come out of it.”

Standing there in front of him, it dawns on me that my introverted self is actually conversing with a stranger I would’ve otherwise avoided. But where my mind really gets, uh, blown, is when Mr Nakamura compares his interpretation of the gallery to what he’s overheard from visitors.

“When some visitors came in, you could see that they were visibly uncomfortable and I didn’t know why. They then started talking about what latex meant to them, which in some cases was bondage, and corroborated their theory with the imagery of ropes, plastic and the sex toys in the room. It made sense and since then, I haven’t been able to see the artwork in quite the same way!” he says, the excitement in his voice peaking.

As I pick my jaw up off the floor, Mr Nakamura goes on to share that after spending so much time around the artwork, he’s begun to realise just how much presentation can affect perception.

“If a person presents himself as cheerful and happy, that’s how the world will see him. But is that all there is to it?”

Elsewhere on the same floor, twenty-three-year-old Ms Rebecca Chong whispers a soft hello as I enter “An Exposition”, an installation created by artist Hilmi Johandi.

This then, is perhaps why the fresh graduate from NTU’s school of Art, Design and Media felt a bit sombre when she first laid eyes on the space.

“I was initially very intrigued because the room is dimmer than what you’d expect for the subject. Some visitors say the room is sparse but I think it’s the artist’s way of presenting memories.”

As I take a closer look around the space, I’m inclined to agree. For someone trying to remember a place or time, the room’s negative space is a powerful yet haunting reminder of the gaps in one’s memory.

“I feel that it’s my role to at least pique the interest of visitors and give them a fuller picture, so I’ll really try to listen and eavesdrop whenever there are guided tours or when the artists themselves pop by to give talks,” she tells me.

“I don’t want to misrepresent their work because it’s not fair to the artists. Especially if they’ve spent so much of their lives researching the subject.”

While the artwork isn’t exactly hers, Ms Chong feels a vague sense of ownership over them and seeks to ensure that they’re properly looked after. Needless to say, she believes that art is important.

“It helps you to understand both yourself and other people more,” Ms Chong says, “For example, when you see something that resonates with you, you start to wonder why it does and if others feel the same way.”

To Ms Chong, art teaches empathy and tolerance as well. Because the artwork and backgrounds of the artists are so diverse, she’s learnt to better appreciate different opinions or perspectives since no single one is better than another.

“Art also trains you to open your mind, senses and even heart because many of these artworks aren’t just visually intriguing but can be appreciated in so many other ways. You just have to pay attention.”

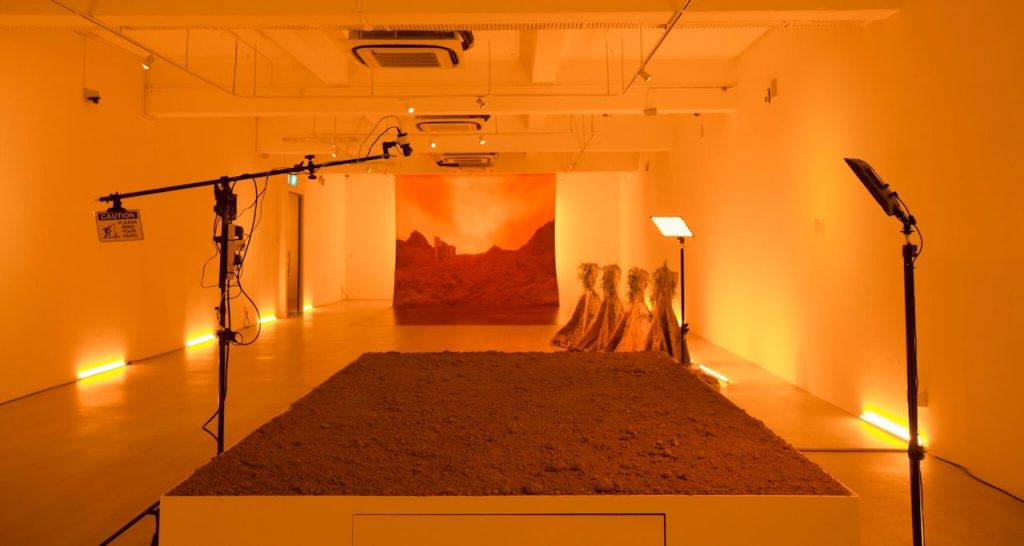

Yet paying attention, as I soon realise, is much easier said than done. In the gallery which houses “Pragmatic Prayers for the Kala at the Threshold” by artist Zarina Muhammad, I still get the feeling that I’m in way over my head.

Luckily, Mr Ashyll, a part-time gallery sitter of four months, is on hand to help me out.

I’m still very much confused. All the effigies, idols and artefacts in the gallery look deeply sacred, so I ask Mr Ashyll if the installation is meant to be religious.

“That’s a very common misconception amongst visitors actually. People tend to assume that because the installation is deeply steeped in Malay history, all of this is related to Islam when in actual fact, it’s not. Culture and religion might be very closely related but they’re still two separate things.

To me, all of these idols are empty vessels which spirits can occupy and inhabit. So I view them as guardians and protectors of certain historical beliefs.”

Mr Ashyll tells me that he also receives many queries about the video presentation in the far corner of the room, which happens to be the most “popular” area in the gallery.

Indeed, I too was just about to ask what the scene in which people stood motionless in the sea meant.

“To me I view it as a sort of a purification process. This gallery is meant to be a space where visitors can traverse the three different realms being earth, the underworld, and heaven. So my interpretation is that I guess one gets to be cleansed before you depart to heaven.

Of course, some visitors see it differently and at the end of the day everyone is going to have their own views. It’s totally fine,” he adds, echoing every other person I’ve talked to this afternoon.

The last person I meet is forty-five-year-old Mr Sivakumar, the assistant manager of the Singapore Art Museum.

“The first time I stepped into this gallery I was like, “wow”. There were a lot of things that I probably knew about but when something is presented in a different way, or in a museum, you examine it and have a better understanding of the subject. And I think it’s the same for others as well.

Even though soil is everywhere, people don’t really think or talk about it until you step into this room.”

He’s right. With the fiery-orange lighting in the room mimicking the hues of clay, and a huge vinyl print of a HDB block peeking out behind mountains of soil, one can’t help but feel as if you’re hundreds of meters beneath the earth’s surface, a tiny grain and yet crucial to the life above it.

What many people fail to realise is that art can be found anywhere, and it’s around us all the time. It’s in the scars that follow us in life. Or in the soil beneath our feet. Even the seemingly inconspicuous materials we happen to come across can be considered art.

Many of us (myself included) are quick to dismiss contemporary art as too difficult to understand or appreciate. But from what I’ve learnt today, the open-endedness of the artwork is the point.

Contemporary art is meant to open the mind and channel your thoughts down different avenues. Granted, it’s a lot easier said than done, but discussing the artwork with the gallery sitters or even a stranger in the museum really goes a long way in helping to make sense of something.

It’s about seeing things in a new light and from different perspectives. Then, and only then, will the artwork truly come alive and can be appreciated for what it is – a personal, yet not individual expression of imagination.

Results of the President’s Young Talents 2018 will be announced on the 29th of November.